Category Archives: Landscapes

McCarthy: Public Consultation Workshops on Future of Docklands Crucial

Cllr Kieran McCarthy has welcomed ongoing developments in the Docklands quarter of the city from Blackrock through Pairc Uí Chaoimh, the Marina Park to Centre Park Road. “it is clear there in a progressive energy in this corner of the city at this present moment; in continuing progress and to meet the current economic climate and the demand for housing, a new Cork City Docks Local Area Plan will replace the South Docks Local Area Plan 2008 and the expired North Docks Local Area Plan 2005. The Tivoli Docks LAP will be a new plan. All of these area have seen lands been incorporated into NAMA and it is very important that their future is unlocked and older plans are amended”.

“As a first step, the City Council is undertaking a pre-plan issues exploration consultation and invites all stakeholders and interested parties to identify the issues that they feel need to be addressed in the proposed LAPs and how the areas should be redeveloped. The Cork City Docks (Local Area Plan) Issues Paper and the Tivoli Docks (Local Area Plan) Issues Paper can be viewed at www.corkcity.ie/localareaplans”.

The public Consultation workshop to promote discussion about the future of the Cork City Docks and Tivoli Docks is being held on Tuesday 20 June 2017 between 6pm-9pm (with light bites between 5pm-6pm) at the Clayton Hotel, Lapp’s Quay, Cork. Workshop places are limited and the City Council asks that interested people RSVP in advance of the meeting by emailing planningpolicy@corkcity.ie or ringing 021– 492-4086 / 021-492-4757. The City Council aims to ensure a good balance in those participating in the event. Cork City Council invites written submissions from you to inform the plan-making processes. The deadline for the receipt of submissions is 1.00pm on Friday 7 July 2017.

McCarthy: Book Twenty Explores Secret Cork

Cllr Kieran McCarthy’s 20th book has hit Cork bookshelves and it entitled Secret Cork. Published by Amberley Press, the new publication is a companion volume to Kieran’s Cork City History Tour (2016) and contains sites that Kieran has not had a chance to research and write about in any great detail over the years. Secret Cork takes the viewer on a walking trail of over fifty sites. It starts in the flood plains of the Lee Fields looking at green fields, which once hosted an industrial and agricultural fair, a series of Grand Prix’s, and open-air baths. It then rambles to hidden holy wells, the city’s sculpture park through the lens of Cork’s revolutionary period, onwards to hidden graveyards, dusty library corridors, gazing under old canal culverts, across historic bridges to railway tunnels. Secret Cork is all about showcasing these sites and revealing the city’s lesser-known past and atmospheric urban character.

Cllr McCarthy notes; “Cork’s story is really enjoyable to research and promote. I still seek to figure out what makes the character of Cork tick. I still read between the lines of historic documents and archives. I get excited by a nugget of information that completes a historical puzzle I might have started years ago. I still look up at the architectural fabric of the city to seek new discoveries, hidden treasures and new secrets. I am still no wiser in teasing out all of Cork’s biggest secrets. But I would like to pitch that its biggest secret is itself, a charming urban landscape, whose greatest secrets have not been told and fully explored”

Continuing Cllr McCarthy highlighted that we all become blind to our home place and its stories; “we walk streets, which become routine spaces – spaces, which we take for granted – but all have been crafted, assembled and storified by past residents. It is only when we stand still and look around that we can hear the voices of the past and its secrets being told”.

“Cork’s story has been carved over many centuries and all those legacies can be found in its narrow streets and laneways and in its built environment. The legacy echoes from being an old ancient port city where Scandinavian Vikings plied the waters 1,000 years ago – their timber boats beaching on a series of marshy islands – and the wood from the same boats forming the first foundations of houses and defences”.

“Themes of survival, living on the edge, ambition, innovation, branding and internationalisation are etched across the narratives of much of Cork’s built heritage and are among my favourite topics to research. Indeed, I fully believe that these are key narratives that Cork needs to break the silence on more and this is a book constructed on those themes”.

Secret Cork is available in Cork bookshops or online at Amberley Press.

McCarthy: A Larger Marina Park should be Pursued

Press Release

Independent Cllr Kieran McCarthy has welcomed the site preparation phase for phase one of the Marina Park, which comprises new riverside public sports, adventure and ecology Park – all of which wraps around the new Pairc Ui Chaoimh. “The creation of Marina Park pursues a 170-year-old plan for the area to develop a park worthy of being named City Park, notes Cllr Kieran McCarthy.

Cllr McCarthy is the author of a publication on the history of the Munster Agricultural Society and gives historical walking tours of the Marina and surrounding suburbs.

“A larger municipal park was proposed in the area in the 1840s by Cork Corporation’s Engineering department. The reclamation of land behind the Navigation wall or dock now part of the Marina Walk was accelerated through the provision of the Atlantic Pond in the 1840s, the opening of the City Park racecourse in 1869, the new showgrounds in 1892, shortly followed by a GAA pitch at the turn of the twentieth century and the new ford Factory in 1917. It is now through European funding of e.4m that we can begin to pursue that dream even further and create a super public amenity in the area. In addition, such heritage DNA should also be remembered in the footprint of the park. I welcome that part of the old stands are to become part of Marina park”.

“There are also lessons to be learned from other parks in the city. Despite the circa e30m investment into the nearby 180-acre Tramore Valley park it remains closed due to staffing shortages and funding challenges in the Council. I don’t want to see a brand new Marina Park and then no funding available to staff it, maintain it or open it”.

“There is also the elephant in the room that there may be room to create an expanded Marina Park. With all of the development land of former Howard Holdings in NAMA, it remains to be seen how these lands will be developed. I have advocated that part of the South Docklands plan will have to be revisited and redesigned. It would be great to have an elongated Marina Park through whatever new plan emerges. Public amenity space needs to be at the heart of the emerging Docklands quarter”.

Pictures, McCarthy’s Make a Model Boat Project, The Lough 2017

Second Call: McCarthy’s ‘Make a Model Boat Project’ 2017

Cllr Kieran McCarthy invites all Cork young people to participate in the eighth year of McCarthy’s ‘Make a Model Boat Project’. All interested must make a model boat at home from recycled materials and bring it along for judging and floating at Cork’s Lough on Wednesday 24 May 2017, 6.30pm. The event is being run in association with Meitheal Mara and the Cork Harbour Festival. There are three categories, two for primary and one for secondary students. The theme is ‘Cork Harbour Boats from 100 years ago inspired by the 1917 Naval commemorations’, which is open to interpretation. There are prizes for best models and the event is free to enter. There are primary and secondary school categories. Cllr McCarthy, who is heading up the event, noted “I am encouraging creation, innovation and imagination amongst our young people, which are important traits for all of us to develop; places like the Lough are an important part of Cork’s natural and amenity heritage and in the past have seen model boat making and sailing. For further information and to take part, please sign up at www.corkharbourfestival.com.

The Cork Harbour Festival will bring together the City, County and Harbour agencies and authorities. It connects our city and coastal communities. Combining the Ocean to City Race and Cork Harbour Open Day, there are over 50 different events in the festival for people to enjoy – both on land and on water. The festival begins the June Bank Holiday Saturday, 3 June, and ends with the 10 June 28km flagship race Ocean to City – An Rás Mór. Join thousands of other visitors and watch the hundreds of participants race from Crosshaven to Blackrock to Cork City in a spectacular flotilla. Cllr McCarthy noted: “During the festival week embark on a journey to explore the beautiful Cork Harbour – from Mahon Estuary to Roches Point – and enjoy open days at heritage sites, and lots more; we need to link the city and areas like Blackrock and the Marina and the harbour more through branding and tourism. The geography and history of the second largest natural harbour in the world creates an enormous treasure trove, which we need to harness, celebrate and mind”.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 11 May 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 11 May 2017

The Wheels of 1917: The Queenstown Patrol

Sir Lewis Bayley of the British Navy gave Commander Joseph Taussig’s four days to mobilise the six American destroyers, which arrived into Queenstown on 4 May 1917 (see last week’s column). In the ensuing days of preparation work and strategy creation, stories were shared of the engagement between the British flotilla leaders Swift and Broke on one side and six German destroyers on the other side, as well as German submarines.

According to Taussig’s diary entries, by 7 May 1917, a naval strategy had been worked out – some of the core points of which are below. The destroyers, British and American, were to work in seven pairs for the short term. Taussig’s fleet were to replace the larger British naval destroyers, which in time were to be sent back to the British base at Plymouth in the English Channel. The destroyers were to be made to work six days at sea. Ships chasing a submarine on the sixth day with two thirds of their fuel gone were to stop chasing their folly and come home. Shelter was to be taken in bad weather. When ship-wrecked crews were picked up, they had to be brought directly into the harbour. As German submarines were returning to torpedoed and floating steamers to get metal out of them, destroyers were encouraged to wait and approach them with the sun at their back. If they met what appeared to be a valuable ship in dangerous waters they were to escort her. If an SOS call was received, and they thought they could be in time to help, they were to go and assist the ship; but as a rule, they were not to go over 50 miles from their area.

Destroyers were to be careful not to ram boats to sink them as cases had occurred whereby they had been left with bombs in them ready to explode when struck. Senior officers of destroyers were to give the necessary orders with regard to what speed to cruise at, orders for zig-zagging; they knew the capabilities of their ships best. When escorting, it had been found best as a rule to cross from bow to bow, the best distance away being about 1,000 yards; however, this depended on a myriad of factors, which included sea conditions and visibility. Reports of proceedings were not required on arrival in harbour unless for some special reason such as signalling for preparing for attacking submarines and rescuing survivors.

Much confidence was placed in the strategic mind of Commander Taussig. Like his father before him, Joseph was noted as well-known figure with exceptional ability as a naval officer. Joseph Knefler Taussig was born of American parentage in 1877 in Dresden, Germany, where his father, who also became a rear admiral in the Navy, was stationed. His father was Edward David Taussig, a native of St Louis, Missouri, and his mother, Ellen Knefler Taussig, was a native of Louisville, Kentucky. Joseph’s father graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1867 and retired in 1909, ten years after his son completed his work at the Academy. Joseph graduated from high school in Washington, DC, in 1895 and was appointed to the Naval Academy that same year. At Annapolis, young Taussig was known primarily as an all-around athlete: he won first-place medals in the high jump, broad jump, and 200-yard hurdles; he was a member of the crew, varsity football team, and runner-up for the wrestling team.

In 1900, whilst a midshipman, a member of the naval forces, Joseph was sent to China with other members to squash a violent anti-foreign and anti-Christian uprising that took place in China between 1899 and 1901. Near Tientsin, Joseph was wounded and sent to a hospital to recover with an English Captain John Jellicoe who was Chief-of-Staff to Admiral Seymour, who was in charge of the British forces. It was a legend of sorts that grew up around Joseph and that diplomatic relations were something not new to him. In addition, a letter from Admiral Jellico was handed to Joseph in Queenstown in May 1917 welcoming him and the American Navy to the battle zone.

In a public speaking engagement at Carnegie Hall, New York on 30 January 1918, Joseph Taussig recalls that in the three weeks before his arrival to Queenstown, German submarines had sunk 152 British ships in the nearby Atlantic area. Hence, he had depth bombs installed so as to fight off the submarines. He noted in his speech; “we escorted many ships and we saved many lives. I cannot say we sunk any submarines. The submarine I found was a very difficult bird to catch. He always sees you first. Only once did my vessel, in seven months, succeed in actually firing at a submarine. He then went down after the fifth shot was fired. At that he was five miles away. But they were afraid of the depth bombs. I saw results on several occasions, which led me to believe that I had at least damaged one of two”.

Joseph Taussig found the patrol duty very difficult as the ocean was strewn with wreckage for a distance of 200 miles off shore. Judgement was important; “it was hard to tell a telescope when we saw one. We fired at fish, floating spars and other objects because we could afford to take a chance. The submarines grew less active or did less damage as the summer [of 1917] wore on”.

Captions:

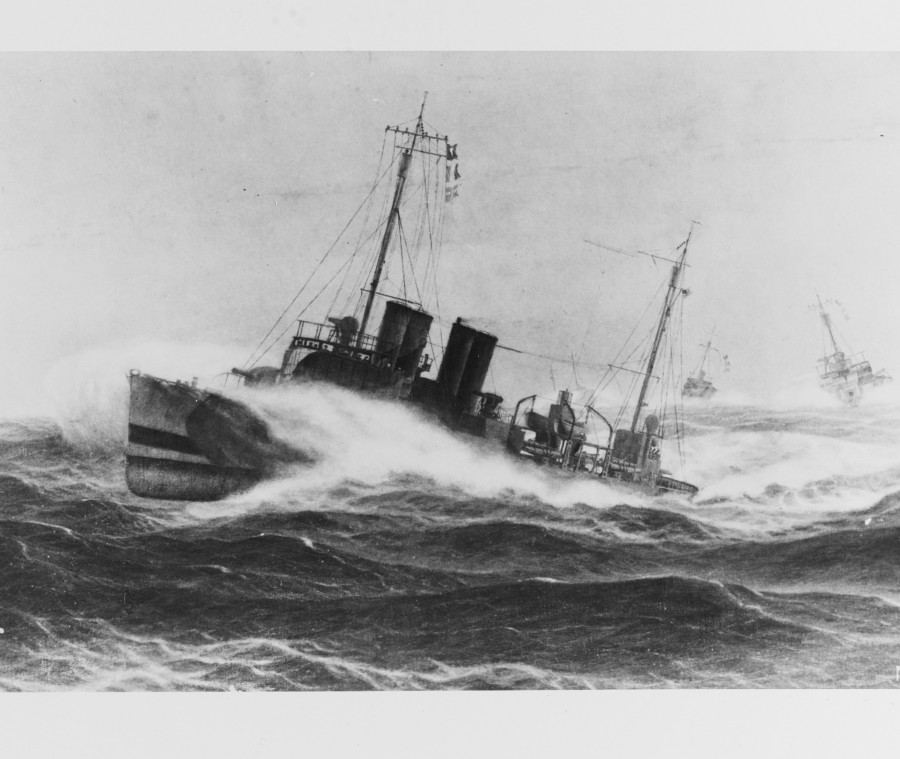

894a. Painting by Burnell Poole, 1925. Depicting three U.S. Navy destroyers fighting heavy seas while on World War I escort service, off Queenstown, Ireland (source: Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington).

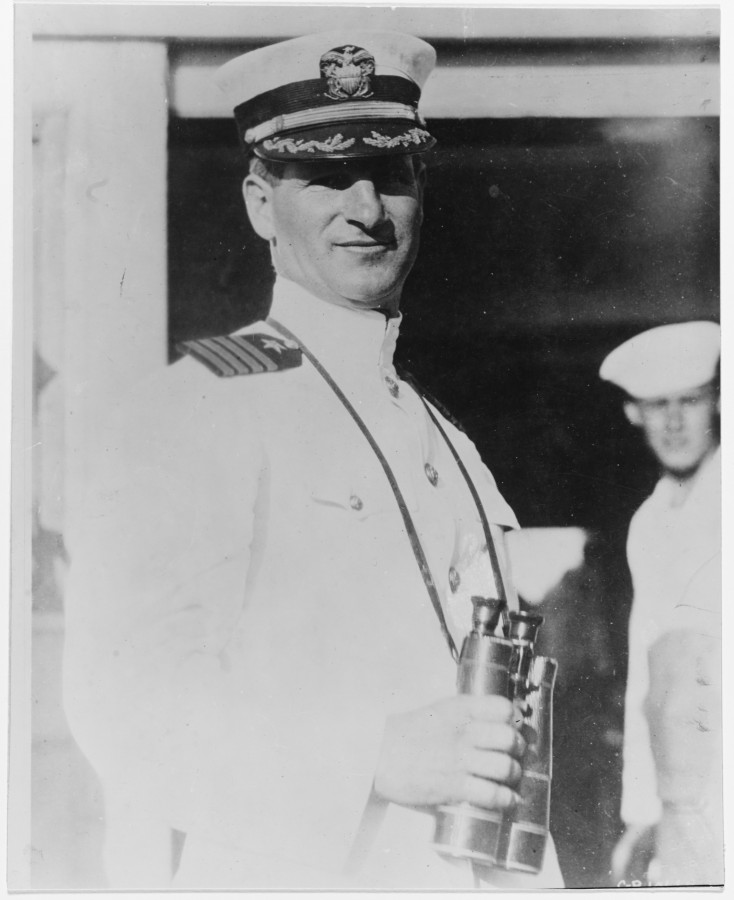

894b. Commander Joseph K Taussig in the 1920s (source: Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington).

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 27 April 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 27 April 2017

Kieran’s May Historical Walking Tours

Early summer is coming and the weather is improving. So below are details of the next set of my public walking tours for the first week of May,

Tuesday 2 May 2017, Historical Walking Tour with Kieran of Eighteenth Century Cork, from the walled town to an eighteenth-century Venice of the North; meet outside Cork City Library, Grand Parade, 6.45pm, (free, 2 hours, finishes on St Patrick’s Street)

For nearly five hundred years (c.1200-c.1690), the walled port town of Cork, built in a swamp and at the lowest crossing point of the River Lee and the tidal area, remained as one of the most fortified and vibrant walled settlements in the expanding British colonial empire. However, economic growth as well as political events in late seventeenth century Ireland, culminating in the Williamite Siege of Cork in 1690, provided the catalyst for large-scale change within the urban area. The walls were allowed to decay and this was to inadvertently alter much of the city’s physical, social and economic character in the ensuing century.

One of the most elegant additions to eighteenth century Cork was the Exchange or Tholsel, which was built on the site of Roches Castle (now the site of the Catholic Young Men’s Society hall on Castle Street). It was an important building of two stories. On its opening in 1710 the Council ordered the upper floor room be established as a Council Chamber with liberty for the Grand Jury of magistrates and landlords to sit. The lower part was used for commercial purposes. where a pedestal known as “the nail”, was used for making payments (still in existence in Cork City Museum). In later times the room was used for public sales. A figure of a dragon made of copper and gilt surmounted the cupola of the building as a weather vane. The Exchange declined as a market in time – through the erection of a Corn Market on the Potato Quay (popularly known as the Coal Quay) and improved facilities for the transaction of business offered to merchants.

Wednesday 3 May 2017, Historical Walking Tour with Kieran on the Walk of the Friars, from Red Abbey through to Greenmount; meet at Red Abbey Square, 6.45pm, (free, 2 hours, finishes near Deerpark)

The central bell tower of the church of Red Abbey is a relic of the Anglo-Norman colonisation and is one of the last remaining visible structures, which dates to the era of the walled town of Cork. Invited to Cork by the Anglo-Normans, the Augustinians established an abbey in Cork, sometime between 1270 AD and 1288 AD. It is known that in the early years of its establishment, the Augustinian friary became known as Red Abbey due to the material, sandstone, which was used in the building of the friary. It was dedicated to the Most Holy Trinity but had several names, which appear on several maps and depictions of the walled town of Cork and its environs. For example, in a map of Cork in 1545, it was known as St Austins while in 1610, Red abbey was marked as St. Augustine’s.

In the mid eighteenth century, part of the buildings of Red Abbey were used as part of a sugar refinery. This refinery was burnt down accidentally in December 1799. Since then, the friary buildings with the exception of the tower have been taken piecemeal. The tower is maintained by Cork City Council who were donated the structure by the contemporary owners in 1951 and also own other portions of the abbey site. Today, the tower of Red Abbey approximately thirty metres high is one of Cork’s most important protected historic structures. The remaining tower cannot be climbed but medieval architecture can still be on the lower arch of the structures and in the upper windows. The adjacent street names of Red Abbey Street, Friar’s Street and Friar’s Walk also echoes the days of a large medieval abbey in the area.

Thursday, 4 May 2017, Historical Walking Tour with Kieran of Blackrock Village, from Blackrock Castle to Nineteenth Century Houses and Fishing; meet outside Blackrock Castle, 6.45pm, (free, 2 hours, finishes at railway line walk)

The earliest and official evidence for settlement in Blackrock dates to c.1564 when the Galway family created what was to become known as Dundanion Castle. Over 20 years later, Blackrock Castle was built circa 1582 by the citizens of Cork with artillery to resist pirates and other invaders. In the early 1700s, the prominent Tuckey family, of which Tuckey Street in the city centre is named, became part of the new social elite in Cork after the Williamite wars and built part of what became known in time at the Ursuline Convent. The building of the Navigation Wall or Dock in the 1760s turned focus to reclamation projects in the area and the eventual creation of public amenity land such as the Marina Walk during the time of the Great Famine. Soon Blackrock was to have its own bathing houses, schools, hurling club, suburban railway line, and Protestant and Catholic Church. The pier that was developed at the heart of the space led to a number of other developments such as fisherman cottages and a fishing industry. This community is reflected in the 1911 census with 64 fishermen listed in Blackrock.

Captions:

882a. Sketch of Cork Exchange, c.1750 (now the site of YMCA hall, Castle Street, one of the city’s primary market sites, subject of eighteenth century Cork tour (source: Cork City Library)

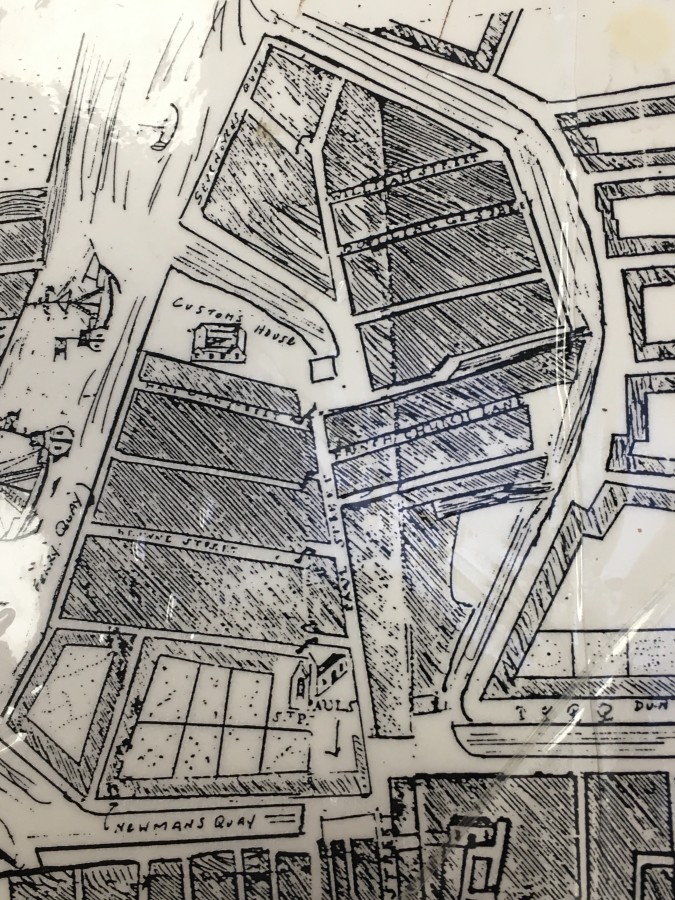

882b. Map of north east marsh, Paul Street & St Paul’s Church, 1726 by John Carty (source: Cork City Library)

Cllr McCarthy: May Historical Walking Tours