13 January 2021, “Cllr Kieran McCarthy who has a keen interest in history and archaeology gave a brief history of the buildings in that area of the city. ‘It is the site of an old fort called Cat Fort from the 1690s. Cat Fort was an additional barracks to Elizabeth Fort which was created around 1698. It is said that it began its life as some sort of ditch on a waterless moat on that side of Elizabeth Fort”, Councillors to seek answers on collapsed Cork city wall, Councillors to seek answers on collapsed Cork city wall (echolive.ie)

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 14 January 2021

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 14 January 2021

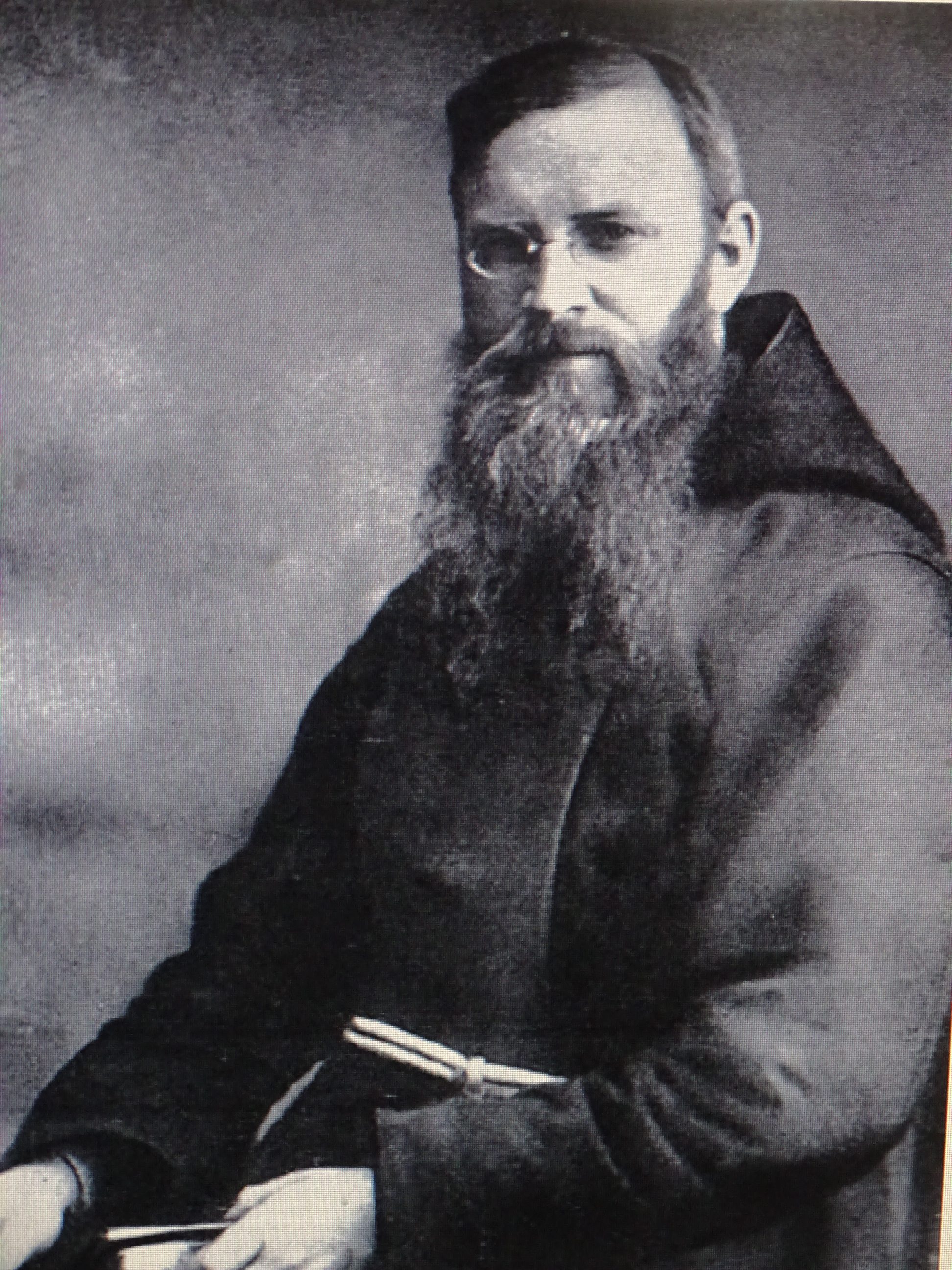

Journeys to a Truce, 1921: The Trial of Fr Dominic

Following the sad events of Terence MacSwiney’s funeral on 31 October 1920, the Lord Mayor’s Capuchin chaplain Fr Dominic O’Connor received death threats in Cork. For his own safety, the Father Provincial sent him to Kilkenny and then to Dublin. Fr Dominic arrived in Dublin in November 1920. He rarely left the house and during part of that time he also became unwell.

On 16 December 1920, a party of military raided the Capuchin Franciscan Monastery situated at Church street, Dublin. Fr Aloysius in his Bureau of Military History witness statement (WS207) records that the raid on the Monastery took place about 10.20pm on the night of 16 December and continued till close on 4am on 17 December. There were circa 300 soldiers engaged in the operation and some sixty fully armed men occupied the Monastery. The soldiers got over the railings, gates and walls — armoured cars and care with powerful searchlights patrolled the streets adjoining. All apartments of the house were minutely searched. The church, confessionals and sacristy were all visited and presses and desks within opened. Books, documents, miscellaneous and private letters were thoroughly examined. Beds and even waste paper baskets were examined.

Fathers Dominic and Albert were placed under arrest and given about a half an hour to prepare, being under guard during that time. At about 1.30am they were taken to Dublin Castle under armed escort. Father Albert was released after a few hours and was home by 4.30am but Father Dominic was detained. On 23 December he was removed after curfew hours in an armoured car to the Old Prison, Kilmainham.

Father Dominic remained in solitary confinement. Fr Aloysius succeeded in obtaining permits to visit him and to converse with him daily in presence of a guard. He arranged to provide him, during the period of his detention prior to his trial, with some extras in food and with necessary clothing. But Fr Dominic had to conform to the ordinary prison diet and to sleep on the floor with merely a small mattress under him. He was to be kept within his cell under lock and key except for an hour’s exercise, morning and evening. After the first week he could celebrate Mass nearly every morning.

No notification of the charge was made until late on Wednesday 5 January 1921. Fr Dominic had no opportunity of consulting a solicitor until 6 January whilst the court martial was fixed for 10.30am on 8 January. The lack of a forthcoming charge and that he was a priest meant that the detention of Fr Dominic became a large media story, not alone in Ireland, but in many other countries.

On 9 January 1921, Fr Dominic, was charged before a Field General Court Martial at Kilmainham Courthouse. The Cork Examiner of the time, through their reporter, records that at Kilmainham Court, though the proceedings were open to the public, the attendance was of limited nature. In the precincts of the building several soldiers were on duty, and every person seeking admission to the courthouse was carefully searched. Prior to the opening of the court Fr Dominic was detained by four armed soldiers in a passage leading to the court.

For security reasons, when the court assembled the press representatives and public were requested to retire and the order was carried out. Fr Dominic was then accompanied by his solicitor as they entered the space. After a short time, the press and public were again admitted, and the proceedings commenced. The Court consisted of three military officers assisted by a Judge Advocate or legal adviser.

Fr Dominic was charged on two counts – that he was making a letter statement in a house in Brixton London “to cause disaffection to his Majesty” and secondly that whilst in Dublin he had in possession a “memorandum tablet” or notebook containing statements – the publication of which would be likely “to cause disaffection to his Majesty”.

Fr Dominic’s solicitor Mr O’Connor noted that he was instructed not to appear on Fr Dominic’s behalf. Fr Dominic denied the jurisdiction of the court to try him. At that stage Mr O’Connor then left the court room.

Father Dominic then took the stand and refused to recognise the Court, giving as his reasons that he was an ecclesiastic who could only be tried by an ecclesiastical court, and as an Irishman he objected to the court not being constituted “by the will of his fellow-countrymen”. He critiqued that in the first charge it was only random words on a letter the prosecution had and in the second charge, the notebook held the statements of Terence MacSwiney who was in the later stages of his 74-day Hunger Strike. The trial was detailed and still ended with the charges against Fr Dominic.

At the conclusion of the evidence the Court closed, and Father Dominic remained in custody awaiting the proclamation of his sentence, which was not announced to him until 29 January. The sentence was five years’ penal servitude, with two remitted, i.e. three years’ penal servitude.

On 31 January 1921 Father Dominic was led handcuffed under military escort to a boat at Dún Laoghaire and in the same manner from Holyhead to London. In the prison at Wormwood Scrubbs his clerical attire was taken from him and he was garbed in ordinary criminal convict clothes, and handcuffed. He was taken to Parkhurst Convict Prison in the Isle of Wight. There he was bound by the conventional convict regime regarding dress, diet, and labour (though his hair and beard were not cut).

Fr Dominic was released in a general amnesty in January 1922 pursuant to ratification by Dáil Éireann of the Anglo–Irish treaty.

Missed one of the 51 columns last year, check out the indices at Kieran’s heritage website, www.corkheritage.ie

Caption:

1082a. Fr Dominic O’Connor, c.1920 (source: Irish Capuchin Provincial Archive)

Kieran’s Question to CE and Motions, Cork City Council Meeting, 11 January 2021

Question to the CE:

To ask the CE for an update on repair work on Parliament Bridge on its north-western side? (Cllr Kieran McCarthy).

Motions:

That the public lights within the lamps on the National Monument on the Grand Parade be repaired (Cllr Kieran McCarthy).

That the public lights within the lamps on South Gate Bridge be repaired (Cllr Kieran McCarthy).

To get a report on the status of the Traffic Operations review of the current demand for EV charging points on public roads and in public spaces, as began last year (Cllr Kieran McCarthy).

To review traffic speeds on the main road outside Foxwood and Monfield, Garryduff and to erect further slow down signs and mind children signs as appropriate (Cllr Kieran McCarthy).

Cllr McCarthy: Historic City Centre Apartment Space Offers great prospects of Urban Renewal

8 January 2021, “Independent Cork city councillor Kieran McCarthy also welcomed the plans. ‘There is so much empty property within the city centre especially over the shops that would make great accommodation space plus also offer great prospects of urban renewal’, Cork City Council gives green light to apartment plans for Patrick Street,

Cork City Council gives green light to apartment plans for Patrick Street (echolive.ie)

Cllr McCarthy commissions two new street art murals on Douglas Road, January 2021

Independent Cllr Kieran McCarthy continues his commissions of street art on Douglas Road. In recent weeks, two new pieces have emerged on traffic switch boxes. The first mural, which is located at Cross Douglas Road, is that of Terence and Muriel MacSwiney who lived at 5 Eldred Terrace in 1917.

Cllr McCarthy highlighted: “There was a commemorative plaque erected on the wall of their former house in June 1980 but unfortunately the plaque was taken down a few months later. There have been calls within the Ballinlough area and Douglas Road by locals to once again mark the story from over hundred years ago of the MacSwineys living within the local community. This mural’s central image is from an old photograph of the couple whist the rose motif is a nod to the always beautiful adjacent flower shop.

The second mural is opposite the entrance to St Finbarr’s Hospital. Cllr McCarthy noted: “The mural has the theme of “hold firm” and is dedicated to healthcare staff within the hospital who have held firm against COVID-19. The mural adds to the existing street art mural, which was painted Kevin O’Brien outside CUH last year”.

“It has been great to commission artist Kevin O’Brien again. This is my sixth commission with him. He really brings ordinary municipal utility boxes to life with his creativity, imparting uplifting and positives messages. Roads such as Douglas Road are well walked everyday, so it is great to bring his work into heart of suburban communities, concluded Cllr McCarthy.

Artist Kevin O’Brien noted: “Street art is a fantastic way to improve the aesthetic of urban areas and build a sense of character in communities, but beyond that, with cultural spaces currently closed, the availability of street art in public spaces takes on an even greater importance”.

Pictures: Paths of Snow, Japanese Gardens, Ballinlough, 7 January 2021

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 7 January 2021

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 7 January 2021

Journeys to a Truce, 1921: Excommunication and Ambushes

Mid to late December 1920 coincided with the continued cleaning up of the burnt out ruins of St Patrick’s Street. In addition, there was fall-out from the decree issued by Bishop of Cork Daniel Cohalan on 12 December 1920, that the penalty of excommunication would be imposed on IRA men in the Cork Diocese if they continued to carry arms against the Crown forces.

Bishop Cohalan had intervened during Easter Week 1916 and was responsible then for influencing the decision of the standing down of Cork City Irish Volunteers. His actions then were believed to be motivated by concern for the peace and safety of the citizens and in December 1920 his actions were also driven by peace and safety. But the end of 1920, the Volunteers were on a full war footing and there was anger across different levels of Cork society about the Burning of Cork.

Michael O’Donoghue, Engineer, 2nd Battalion in Cork Brigade No.1, in his witness statement in the Bureau of Military History (WS 1741) details that the reaction in Cork was immediate and emphatic to the Bishop’s decree. He notes that a large portion of the Catholic population were disappointed at it and shocked and angered as he describes it as “its anti-national bias”. More than half of the congregation walked out in protest from the North Cathedral during his Sunday sermon and decree issuing.

However instead of the decree stopping violence, it increased. Not a single member of the IRA in Cork ceased their Volunteer activities or eased off in their active military opposition to the Crown forces. On the contrary, city Volunteers pursued their offensive more than ever.

Michael O’Donoghue noted that on the Sunday afternoon of 12 December 1920 he with other Volunteers, were mobilised for republican police duty in St Patrick’s Street at the scene of the fire. They were mainly engaged in salvaging goads, damaged and undamaged, removed from the partly demolished smaller houses. These goods were stored in houses and yards on the north side of Patrick Street. Looters, too, had to be kept in check. He personally thought that these police activities by them were unwise and unnecessary as he felt it exposed them to recognition and identification as Republican forces. He notes: “The idea was to make a spectacular gesture for propaganda purposes to show the Volunteer forces of the Irish Republican Government protecting property and maintaining order in vivid contrast to the disorder and vandalism of the British forces who had run amok”.

Michael Murphy, Commandant, 2nd Battalion, IRA Brigade No.1 in his witness statement (WS1547) takes up the story of IRA activity in the closing days of 1920. On 28 December 1920, by orders of the brigade, men of the 1st and 2nd Battalions entered the newspaper premises of the Cork Examiner and broke up the printing machines with sledge -hammers. Michael highlights that the offices were attacked as they were deemed by the IRAto have too much of pro-British publication output. About fifty men in all took part in this operation. The majority were on armed duty in the vicinity of the printing works, St Patrick Street while the demolition was being carried out.

On 5 January 1921, martial law edicts were intensified across Munster as General Strickland had issued another proclamation. For all breaches of martial law edict in the south, ‘Death’ was the penalty – “for being in possession of arms or ammunition or any lethal firearm, for levying war against the British Crown, for harbouring, aiding or consorting with rebels (i.e. The Irish Republican Army) for wearing military uniform, British or otherwise & or being in possession thereof, the penalty was death by shooting before a firing squad”. The edict continued – “The accused, if he was not shot out of hand on the spot, which, incidentally, was a frequent occurrence, was tried immediately by drumhead court martial, found guilty and banded over to the execution squad”.

On the same day as the Munster martial law edict was enacted, an attack by the IRA on RIC officers was conducted on Parnell Bridge near Union Quay Barracks.

Each evening, shortly after 6 o’clock, it was the custom for a party of 25 to 30 police and Black and Tans to leave the barracks at Union Quay. They would cross the River Lee at Parnell Bridge and there disperse to points in the city. Commandant Michael Murphy arranged to attack this party, using only the company officers in his battalion, the idea being to give all of them experience under fire.

On the evening of 5 January 1921, Michael Murphy, Peter Donovan of C Company, and Christy Healy went by a motor car driven by Michael Coonan to Morrison’s Island. In the car they had a Lewis gun, one of the two Michael Murphy had got in London a few weeks previously. They parked outside Moore’s Hotel, which was almost directly opposite Union Quay Barracks – the River Lee being between them and the barracks at a distance of about 50 to 60 yards. The remainder of their men were posted at Parnell Bridge, Anglesea Street and at points in the neighbourhood, covering approaches to the enemy barracks. The IRA men were armed with revolvers and grenades.

At approximately 6.15pm the police and Tans came out of Union Quay Barracks and, by the time they were ready to move off, they fixed the Lewis gun in position on the roadway outside Moore’s Hotel.

As the enemy party proceeded towards Parnell Bridge, they opened fire with the Lewis machine gun. The first burst killed seven of them and wounded others. Of those not hit some ran back to the barracks and those at the head of the party ran towards Parnell Bridge where they were met with revolver fire and grenades by IRA men stationed there. The affair lasted no more than ten minutes. None of the IRA men were wounded on the occasion.

When the RIC members had all had disappeared, either shot or gone to cover, the IRA members got their Lewis gun back into the car and made for the house of Sean Hyde, a Volunteer officer, in Ballincollig, where the gun was left for a few days before its next outing.

Caption:

1081a. Parnell Bridge, c.1900 from Cork City Through Time by Kieran McCarthy & Dan Breen

Happy new year to everyone. Stay safe.

Missed one of the 51 columns last year, check out the indices at Kieran’s heritage website, www.corkheritage.ie

Kieran’s 2021 Ward Funds, Now Open

The call for Kieran’s 2021 Ward Fund is now OPEN.

Cllr Kieran McCarthy is calling on any community groups based in the south east ward of Cork City, which includes areas such as Ballinlough, Ballintemple, Blackrock, Mahon, Douglas, Donnybrook, Maryborough, Rochestown, Mount Oval and Moneygourney with an interest in sharing in his 2020 ward funding to apply for his funds. A total of E.11,000 is available to community groups through Cllr Kieran McCarthy’s ward funds.

Application should be made via letter (Richmond Villa, Douglas Road) or email to Kieran at kieran_mccarthy@corkcity.ie by Friday 5 February 2021. This email should give the name of the organisation, contact name, contact address, contact email, contact telephone number, details of the organisation, and what will the ward grant will be used for?

Please Note:

– Ward funds will be prioritised to community groups based in the south east ward of Cork City who build community capacity, educate, build civic awareness and projects, which connect the young and old.

– Cllr McCarthy especially welcomes proposals where the funding will be used to run a community event (as per COVID guidelines) that benefits the wider community. In addition, he is seeking to fund projects that give people new skill sets. That could include anything from part funding of coaching training for sports projects to groups interested in bringing enterprise programmes to encourage entrepreneurship to the ward.

– Cllr McCarthy is also particularly interested in funding community projects such as community environment projects such as tree planting, community concerts, and projects those that promote the rich history and environment within the south east ward.

– Cllr McCarthy publishes a list of his ward fund allocations each year on this page.

Christmas Tree Recycling Points, January 2021

Independent Cllr Kieran McCarthy wishes to remind the general public that Cork City Council will provide facilities for the acceptance of Christmas Trees for recycling from householders in Cork City.

Christmas trees may be deposited free of charge at any of the following sites from 2 January to 31 January 2021 – Gus Healy Swimming Pool, Ballinlough (on the green adjacent), Clashduv Park, Togher (adjacent to bring bank site), Ballincollig Regional Park, Ballincollig (on the green adjacent to bring bank site), Murmont Road, Montenotte (on the green adjacent), Sam Allen Sports Complex, Gurranabraher (on the green adjacent), and Tramore Valley Park, South Link Road

Cllr McCarthy noted: “the continuance of this free annual service is to be welcomed. Cork City Council appeals to members of the public to dispose of Christmas trees at these designated locations only. Any persons found disposing of Christmas trees at sites other than the above mentioned will incur a fine”.

The Blessing of a Candle, Christmas 2020

by Cllr Kieran McCarthy

Sturdy on a table top and lit by youngest fair,

a candle is blessed with hope and love, and much festive cheer,

Set in a wooden centre piece galore,

it speaks in Christian mercy and a distant past of emotional lore,

With each commencing second, memories come and go,

like flickering lights on the nearest Christmas tree all lit in traditional glow,

With each passing minute, the flame bounces side to side in drafty household breeze,

its light conjuring feelings of peace and warmth amidst familiar blissful degrees,

With each lapsing hour, the residue of wax visibly melts away,

whilst the light blue centered heart is laced with a spiritual healing at play,

With each ending day, how lucky are those who love and laugh around its glow-filledness,

whilst outside, the cold beats against the nearest window in the bleak winter barreness,

Fear and nightmare drift away in the emulating light,

both threaten this season in almighty wintry flight,

Sturdy on a table top and lit by youngest fair,

a candle is blessed with hope and love, and much festive cheer.

McCarthy Christmas Candle