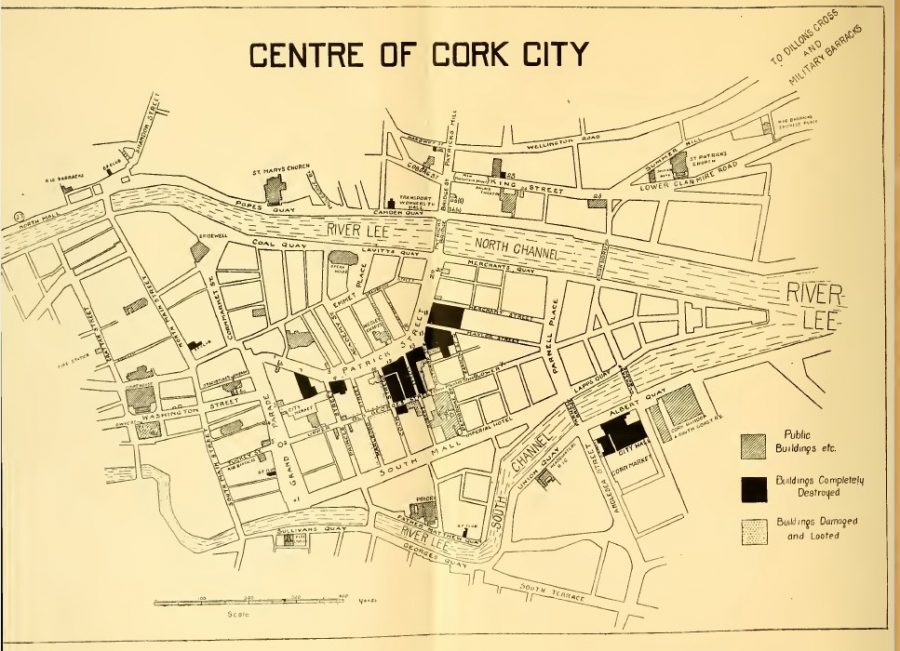

1079a. Map of burnt out sites from Burning of Cork, December 1920 from the Sinn Féin and Irish and English Labour Party publication Who Burnt Cork City (1921).

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 17 December 2020

Remembering 1920: The Aftermath of Arson

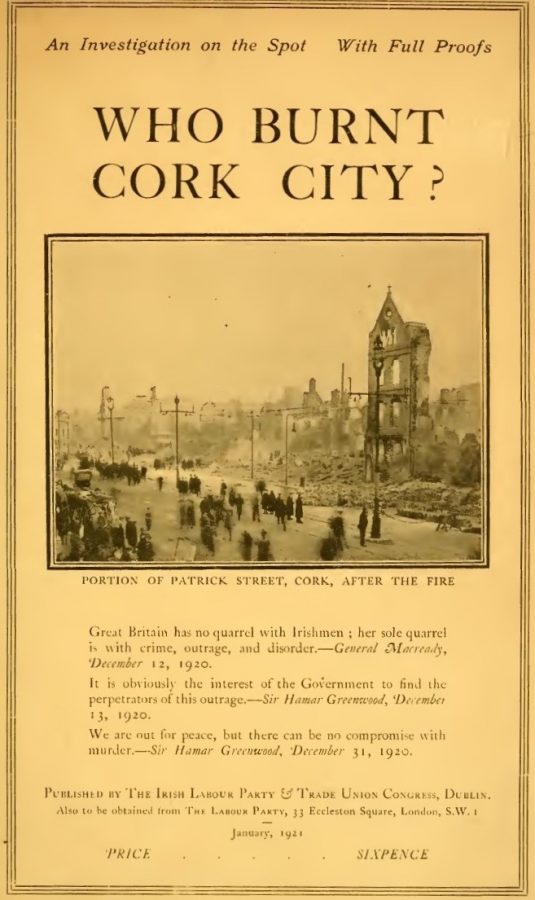

Throughout Sunday 12 December 1920, many willing helpers rendered assistance to the firemen in their challenging duties as fires smouldered after the Burning of Cork the previous night. Streets ran with sooty water, strewn with broken glass, and strong smell of burning. Dublin Fire Brigade with the assistance of firemen from Limerick and Waterford helped Cork Brigade.

On Monday morning, 13 December, the work of clearing away the debris in the widely devastated area was commenced. To keep the public back, rope chains were placed around many streets and their ruined and wrecked buildings. Considerable progress was made as immense quantities of debris were cleared. Representatives from numerous builders’ firms were busily engaged inspecting the ruined premises in the flat of the city and with difficulty trying to save important books and documents from safes. At the gutted City Hall and at the Carnegie Library, it was possible to recover some documents, which were kept in strong safes within the buildings.

On being interviewed by the Cork Examiner, Cork Corporation Engineer Mr Joseph F Delany had already completed a hurried survey. Five acres of property had been destroyed. The St Patrick’s Street business premises from Merchant Street to Cook Street were all gone; the eastern side of the northern section of Cook Street had been demolished, while establishments in Oliver Plunkett Street, Winthrop Street, Morgan Street, Merchant Street, Maylor Street, and Caroline Street were wiped out – in addition to the extensive drapery establishment of Messrs Grant and Company situated between Princes Street and the corner of Grand Parade in St Patrick’s Street.

On Monday 13 December debate ensued in the House of Commons in Westminster, Independent MP and former member of the Irish Parliamentary Party Mr T P O’Connor asked for the particulars of the fires in Cork – “the number of buildings and the value of the property destroyed, the number of persons, if any, killed and wounded, whether the government had the discovered the authors of this series of crimes; whether any of them had been arrested, and whether the government would undertake to bring them to trial at the earliest moment”. Sir Hamar Greenwood, Chief Secretary for Ireland, replied that he had not received a full or even a written report regarding the occurrences. To opposition jeering, he denied knowing who started the fires and rejected the suggestion that the fires were started by the forces of the Crown and that such claims were being used to undermine Government policy in Ireland.

Greenwood argued that “every available policeman and soldier in Cork was turned out to assist and without their assistance the fire brigade could not have got through the crowds and did the work they tried to do”. His contention was that the forces of the Crown had saved Cork from absolute destruction and that the whole event was orchestrated by Sinn Féin. He further related that there were “no incendiary bombs in the possession of the forces of the Crown in Ireland and there are incendiary bombs in the possession of the Sinn Féiners and we are seizing them every week”.

Back in Cork political reaction to Greenwood’s side stepping of responsibly saw full scale anger. The Lord Mayor of Cork, Donal Óg O’Callaghan and Corporation members sent a message to leading MPs rejecting Greenwood’s suggestion that Cork City was burned by any section of the citizen’s and demanding an impartial inquiry.

The immediate follow up at Westminster was the creation of the Court of Enquiry, which was organised between 16-21 December 1920, by Major-General Sir E P Strickland, Commander of the British Sixth Division at Cork. Testimony was taken from 38 witnesses, including thirteen military, eleven police, and nine civilians. A number of Irish civil leaders declined to take part in the enquiry.

The Court stated there was circumstantial proof that K Company of the auxiliary division of the RIC and three members of the RIC were involved in the fire, which later broke out at the Cork City Hall. The remainder of the arson was credited to the fire having disseminated from the original outbreaks, and especially to the incompetence of the local fire brigade. The Enquiry failed to note that firemen had been prevented from controlling the burning by British forces who cut the hoses with bayonets and turned off the water at the hydrants.

While praising the military for its efficiency and discipline and, the Court recognised the outrageous activity of the police to the fact that a higher authority had sent to Ireland ill-disciplined and inexperienced men. The resulting report of the Court of Enquiry was widely referred to as The Strickland Report, though never officially published.

While the burning was admitted in report, for weeks afterwards Sir Hamar Greenwood, minimized it in Cabinet discussions. On 14 February 1921 the Cabinet decided to withhold the Strickland Report and not to establish any tribunal. The Cabinet did conclude that 50 men in K Company were seriously guilty of indiscipline, though they could not be individually identified. The Ministers also decided that the company should be broken up, and its commander suspended.

Meanwhile in Cork, in the absence of an immediate official report, Seamus Fitzgerald, Cork IRA Brigade No.1 penned Who Burnt Cork City. In Seamus’s witness statement in Bureau of Military History (WS1737),he notes that the great majority of the depositions contained in the pamphlet “Who Burnt Cork City” were obtained by him while Cork was still burning.

Seamus conferred at length in the preparation of the pamphlet with its editor, Professor and Sinn Féin Cllr Alfred O’Rahilly, who wrote the foreword to same. Every witness statement had to be sworn, and in no case did any witness refuse, despite the danger attached to same. The pamphlet had to be prepared quickly and published before Hamar Greenwood would make his promised speech in the British House of Commons absolving the British Forces. It was felt that the pamphlet would obviously suffer if published under the aegis of Dáil Éireann or Sinn Féin. It was arranged, therefore, to publish it under the name of the Irish Labour Party with a connection to the English Labour Party.

Caption:

1079a. Map of burnt out sites from Burning of Cork, December 1920 from the Sinn Féin and Irish and English Labour Party publication Who Burnt Cork City (1921).

Happy Christmas to all readers of the column.

Missed one of the 51 columns this year, check out the indices at Kieran’s heritage website, www.corkheritage.ie