Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 25 July 2024

Donoughmore in the Spotlight

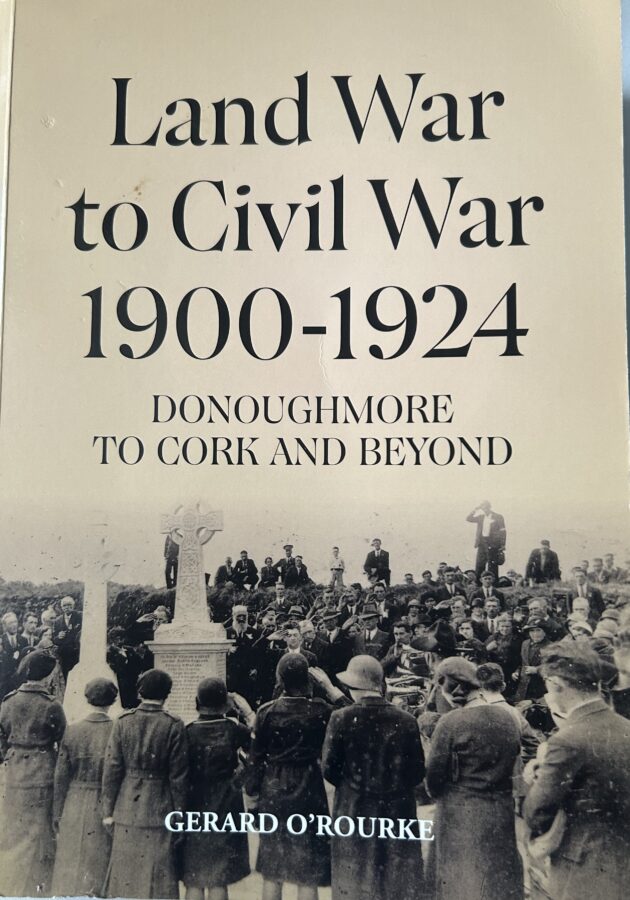

Recently Gerard O’Rourke’s new book Land War to Civil War 1900-1924, Doqnoughmore to Cork and Beyond hit the shelves of Cork book shops. It is a story of conflict and perseverance leading to Irish Independence. It explores, examines, and explains how this was achieved. The book recounts numerous incidents and experiences begins in Donoughmore stopping at various locations through to Cork City and internationally through the stories of the executions of Mrs Lindsay and Compton Smith, Mary Healy and Éamon de Valera, the Wallace Sisters, Dripsey Ambush, Civil War, executions, prison, life, sport, culture, economic life, and daily life.

In his introduction Gerard notes that the aim of the book is to chronicle and document the rise of nationalism and subsequent road to Irish Freedom using Donoughmore, an area 26 km north, north-west of Cork, as a source for investigation. It builds upon stories in Gerard’s second book Ancient Sweet Donoughmore: Life in an Irish Rural Parish (2015). These publications together with an earlier work A History of Donoughmore Hurling and Football Club (1985) completes a significant trilogy of the story of this ancient parish.

Gerard in his introduction further writes about the importance of researching the quest for Irish Independence; “There was a time when talk about what was termed the troubled times was not engaged in, was frowned upon, and brought up too many bitter memories. The advancement of time has changed this and by documenting the narrative of this period we are paying homage to our own. Their sacrifices and work are rightfully highlighted and gives us an insight and appreciation to what was ‘the hidden Ireland?. It more importantly brings context to what we all enjoy today, freedom, independence, self-governance, the scope to make decisions, pursue opportunities all manageable without external intrusion”.

For Cork City Gerard has a really great reflection chapter on the lives and times of Nora and Sheila Wallace, whose story on St Augustine’s Street and their part in the Irish War of Independence in Cork City has come more to the fore in recent years. Gerard draws on family archives including notes and correspondence from the Wallace Sisters. He writes that the Sisters were greatly influenced by tales of Fenians and revolution and a thirst for Independence. They were inspired by the foresight and writings of Pádraig Pearse and James Connolly. The sisters were further enthralled by the focussed and nationalist outlook of Countess Markievicz.

Indeed, Gerard outlines in his research that Nora paid a moving tribute to the countess on her death; “Her proud spirt had learned much or Kathleen Ní Houlihan, and the many ills that needed remedies. One noble heart, one gifted woman, laid aside all loves, and joys to serve her country. Her ideals demonstrated a desire to help the weak, and a firm belief that all difficulties could be overcome by hard work”.

When Countess Markievicz, was court martialled after the Easter Rising her action in kissing her revolver was dramatic as well as poignant. Nora commented on the fight to win; “We who know her, can appreciate fully, what that action implied; the love of a generous heart, and the belief that we should fight to win, coupled with the perfect discipline of a soldier”.

It was in 1911 that a branch of the Fianna organisation was established in Cork. Among those at the inaugural meeting was Tomás MacCurtain and Seán O Hearty. Later, Cumann na mBan was formed in Cork in 1914 and among the women who operated this organisation were Mary MacSwiney, Nora O’Brien, Bridie Conway, Annie and Peg Duggan and Nora and Sheila Wallace.

Gerard further outlines that Nora Wallace’s work with the Volunteers where she made first aid outfits and haversacks brought her increasingly into contact with Tomás MacCurtain and he trusted her with specific intelligence work. After the Easter Rising, she was given special instructions by Tomás to visit Michael Brennan Officer in Command of the East Clare Volunteers at Cork Prison.

In June 1917, the closure of the Volunteer Hall in Sheares Street created a problem for the IRA in Cork. Without a base or recognised meeting place the mechanisms were problematic to direct a war against the Crown Forces. Florence O’Donoghue, Adjutant of the Cork No. 1 Brigade and responsible for communicating with the Brigades units and further afield, saw the potential in using the shop of the Wallace Sisters as a depot for dispatches and a communications centre;

“A depot for dispatches was essential. We found it in the newsagents shop of the sisters Shelia and Nora Wallace…I had been getting my papers there and had known them for some time. They lived over the shop, they worked from eight in the morning until midnight…if any two women deserved immortality for their work…they did. Wallace’s became to all intents and purposes Brigade Headquarters…an indispensable part of the organisation. Shelia and Nora came to know everybody and everyone’s status; they became experts at side tracking persons with no serious business… nothing I could say about their tact and discretion would express adequately my appreciation of the manner at which they did a most difficult and valuable job”.

Gerard details through his research that it took until May 1921 for the British authorities finally tried to curb the actions of the Wallace Sisters and in a letter to the sisters an instruction was given to them to close the shop. Resilient as ever the sisters attained a temporary shop lease in the English Market and continued their work. Less than two months later following the Truce the shop was reopened.

Nora and Sheila Wallace took the Anti-Treaty side and when the Irish civil war broke out, they had to reconsider their activities given they were well known to their former comrades. In that respect despatches were moved promptly. The shop was constantly raided during this period.

€15 sold of each copy of Gerard O’Rourke’s Land War to Civil War 1900-1924, Donoughmore to Cork and Beyond will be donated to cancer care services in Cork.

Caption:

1263a. Front cover of Gerard O’Rourke’s Land War to Civil War 1900-1924, Donoughmore to Cork and Beyond.