Cllr McCarthy: Crowd Control or Missed Opportunity

Arising from the review of limiting tourists numbers at the English Market, Independent Cllr Kieran McCarthy has acknowledged the lesser numbers freeing up trade in the English Market but again makes the point of the opportunity to tell the story of Gastronomy in Cork City and Region; “there is a clear interest in the history of the market and in the food itself; there is a huge opportunity for the region to promote these stories. The English Market is a thriving food venue but some other venue should be developed close by to tell the story of the market viz-a-vis a small food museum and an opportunity to buy English Market hampers of food. The English Market INC can be more than just a market. There is an opportunity to push more of an international story. We can do more to push and showcase Failte Ireland’s food trails of Cork”.

“There are international gastronomy trails in several countries across the world and even college courses in colleges such as CIT which aim to reveal people and key influences in the historical development of regional gastronomy, and the evolution and social, cultural and economic influences of contemporary Irish cuisine and Irish culinary arts”.

“Apart from the physical market, we should also be championing its heritage and legacy in our city and region more in the form of a food centre or on a digital hub; at the moment in time, this is a missed opportunity”.

Question to CE, Cork City Council, 12 June 2017

To ask the CE about solutions being rolled out to tackle Japanese Knotweed? (Cllr Kieran McCarthy)

Report, Expert Advisory Group on the future of local government, 9 June 2017

Report:

https://www.housing.gov.ie/sites/default/files/publications/files/report_of_the_expert_advisory_group_on_local_government_arrangements_in_cork_21-04-17.pdf

Cork City Council has welcomed the publication today by Minister for Housing, Planning, Community and Local Government, Simon Coveney of the report by the Expert Advisory Group on the future of local government in Cork city and county.

Cork City Council Chief Executive, Ann Doherty said: “We welcome the publication of the report by Minister Simon Coveney. With our Elected Members, we shall study its contents in detail and evaluate its implications for Cork city as the economic driver of the region and for its strategic role as an effective and sustainable counterbalance to the Dublin region”.

Under the chairmanship of Jim MacKinnon, the Cork Local Government Arrangements Report was tasked with undertaking a thorough analysis of the issues dealt with in the Cork Local Government Review Committee in September 2015. It was also to examine the potential of local government in furthering the economic and social well being and sustainable development of Cork city and county.

Its terms of reference included considering the strategic role of Cork city as a regional growth centre, an evaluation of governance necessary to safeguard the metropolitan interests of the city, the examination of local government leadership at executive and political levels, the possibility of establishing an office of a directly elected mayor and the possibility of devolving some power from central to local government.

Jim MacKinnon, CBE is a former Chief Planner at the Scottish Government. Former Chairman of An Bord Pleanála and Eirgrid Chair, John O’Connor, former President and board member of the Cork Chamber of Commerce, solicitor, Gillian Keating and Chief Executive of Richmond and Wandsworth Councils, Paul Martin also sat on the expert advisory group.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 8 June 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 8 June 2017

The Wheels of 1917: The Irish Convention

June 1917 coincided with the ground being laid for further national discourse on the future government of Ireland in the form of the Irish Convention. The report of the outcomes of the Convention were compiled and published by Horace Plunkett in 1918.

In a letter dated 16 May 1917 and addressed to Mr John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, the Prime Minister Lloyd George expressed his hope that “Irishmen of all creeds and parties might meet together in a Convention for the purpose of drafting a constitution for their country which should secure a just balance of all the opposing interests”. Invitations were extended to the Chairmen of the thirty-three County Councils, the Lord Mayors or Mayors of the six County Boroughs. The Chairmen of the Urban Councils throughout Ireland were requested to appoint eight representatives, two from each province. The Irish Parliamentary Party, the Ulster Parliamentary Party and the Irish Unionist Alliance were each invited to nominate five representatives.

An invitation was extended to the Roman Catholic Hierarchy to appoint four representatives; the Archbishop of Armagh and the Archbishop of Dublin were appointed to represent the Church of Ireland, and the Moderator of the General Assembly to represent the Presbyterian Church in Ireland. Invitations were also extended to the Chairmen of ‘the Chambers of Commerce of Dublin, Belfast and Cork, and to labour organisations, and the representative peers of Ireland were invited to select two of their number. All these invitations were accepted except by one Chairman of a County Council. Invitations intended to secure representation of the Sinn Féin party and the All for Ireland party were declined, as were the invitations extended to the Trades Councils of Dublin and Cork.

On Thursday evening, 14 June 1917 an inaugural public meeting to discuss the Irish Convention was held in Cork City Hall. The proceedings were published by the Cork Examiner a day later. The meeting comprised merchants, traders, members of the various professions and other citizens of Cork and met to pass a resolution in connection with the future government of Ireland. It was one of the largest and most representative meetings that had assembled in the City for many years, the attendance numbering between 500 and 600, many of whom held very divergent views on the Irish Home Rule situation. Complementary to that at the back of the hall were a section of young men representing Sinn Féin numbering between 40 to 50.

The Chairman Bertram Windle explained that he occupied the chair because the Lord Mayor, T C Butterfield, whom they would naturally expect to find in the chair, considered that he was too closely identified with “party politics” to do so. Windle wished to say distinctly what the meeting was and what it was not; “it was a meeting of the citizens of Cork desirous of promoting the success of the forthcoming Convention”. At this point, one of the young members of Sinn Féin stood up and shouted: “Is the resolution passed last Tuesday night by the Sinn Féin organisation in Cork going to be read here?”. The chairman answered in the negative, and the interruptions from the back of the hall continued. Alderman Beamish rose to a point of order, and asked that all in favour of the object of the meeting stand up. In response every man in the Hall, with the exception of the Sinn Féin representation, rose to their feet.

Mr A F Sharman Crawford, took to the floor, and noted that he felt it a great privilege to propose the resolution, which was the object of the meeting. The resolution was ”That we, merchants, traders, members of the various profession, and other citizens of Cork, in meeting assembled), do hereby cordially welcome the holding of a Convention, to be comprised of Irishmen of all creeds, classes, and politics to consider the most satisfactory scheme for the future Government of Ireland, and we earnestly hope that all the members of such a Convention will enter upon their deliberations with an open mind, and in a broad and liberal spirit fully determined to arrive at some agreement which will tend to the future welfare and prosperity of our common country”.

Mr T B Lillis, of the Munster and Leinster Bank, said he desired to offer a few brief words in support of the resolution. He highlighted that it was not a meeting of politicians, but of business men who were fully representative of the commercial, trading, professional and financial interests of the capital city of Munster. He deemed that “they had the assured conviction, derived from sources of special knowledge which were open to them, that the economic condition of Ireland was never so sound and prosperous as it was at the moment, and their great industry of the land was prospering exceedingly. The prospect of the successful development of our country was never so promising”. At this stage, a young fellow advanced on to the platform and handed the Chairman a Sinn Féin leaflet. Ignoring the intervention, continuing Mr Lillis said they knew that as a result of the “strife and unrest and dissention which were allowed to prevail that the progress of the country was stilted”. The motion was later approved. The Irish Convention held one of its meetings in Cork on 25 September 1917.

Note: June Walking Tours with Kieran, all free, 2 hours

-

Tuesday 13 June, Ballinlough Historical Walking Tour, meet at Beaumont BNS at Beaumont Park, 6.45pm (finishes Ballinlough Road)

-

Wednesday 14 June, Douglas Historical Walking Tour, meet at St Columba’s Church Carpark, 6.45pm (finishes at the Church again)

-

Saturday 17 June, Turners Cross & Ballyphehane Historical Walking Tour, meet at Christ the King Church, Turners Cross, 12noon (finishes a Ballyphehane Park)

-

Saturday 24 June, Old Workhouse Tour, meet at entrance to St Finbarr’s Hospital, Douglas Road, in association with the Friends of St Finbarr’s, 12noon

Caption:

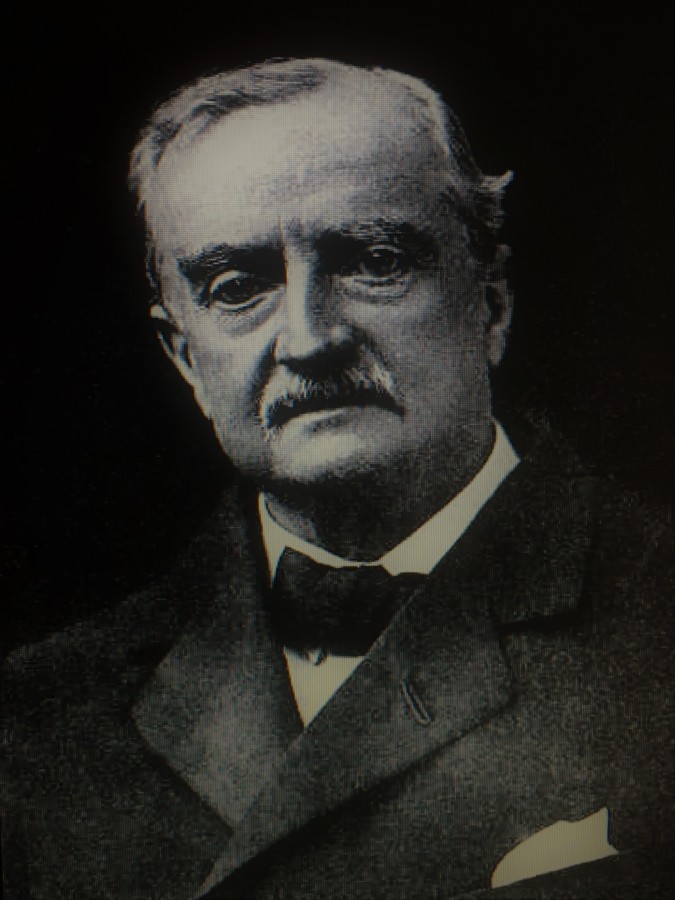

898a. Mr John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, who headed up the roll out of the Irish Convention in the summer of 1917 (source: Cork City Library)

McCarthy: Book Twenty Explores Secret Cork

Cllr Kieran McCarthy’s 20th book has hit Cork bookshelves and it entitled Secret Cork. Published by Amberley Press, the new publication is a companion volume to Kieran’s Cork City History Tour (2016) and contains sites that Kieran has not had a chance to research and write about in any great detail over the years. Secret Cork takes the viewer on a walking trail of over fifty sites. It starts in the flood plains of the Lee Fields looking at green fields, which once hosted an industrial and agricultural fair, a series of Grand Prix’s, and open-air baths. It then rambles to hidden holy wells, the city’s sculpture park through the lens of Cork’s revolutionary period, onwards to hidden graveyards, dusty library corridors, gazing under old canal culverts, across historic bridges to railway tunnels. Secret Cork is all about showcasing these sites and revealing the city’s lesser-known past and atmospheric urban character.

Cllr McCarthy notes; “Cork’s story is really enjoyable to research and promote. I still seek to figure out what makes the character of Cork tick. I still read between the lines of historic documents and archives. I get excited by a nugget of information that completes a historical puzzle I might have started years ago. I still look up at the architectural fabric of the city to seek new discoveries, hidden treasures and new secrets. I am still no wiser in teasing out all of Cork’s biggest secrets. But I would like to pitch that its biggest secret is itself, a charming urban landscape, whose greatest secrets have not been told and fully explored”

Continuing Cllr McCarthy highlighted that we all become blind to our home place and its stories; “we walk streets, which become routine spaces – spaces, which we take for granted – but all have been crafted, assembled and storified by past residents. It is only when we stand still and look around that we can hear the voices of the past and its secrets being told”.

“Cork’s story has been carved over many centuries and all those legacies can be found in its narrow streets and laneways and in its built environment. The legacy echoes from being an old ancient port city where Scandinavian Vikings plied the waters 1,000 years ago – their timber boats beaching on a series of marshy islands – and the wood from the same boats forming the first foundations of houses and defences”.

“Themes of survival, living on the edge, ambition, innovation, branding and internationalisation are etched across the narratives of much of Cork’s built heritage and are among my favourite topics to research. Indeed, I fully believe that these are key narratives that Cork needs to break the silence on more and this is a book constructed on those themes”.

Secret Cork is available in Cork bookshops or online at Amberley Press.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 1 June 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 1 June 2017

The Wheels of 1917: The Age of Public Houses

One hundred years ago this month, meetings were held in Cork City to showcase the rationing of beer and stout. The Beer Restrictions Act cut down the manufacture of such products to one-third of the output. A letter to the editor of the Cork Examiner on 2 June 1917 by a representative of the retail traders Mr Michael O’Mullane explains the effects of rationing. Accordiing to Mr Mullane the curtailment had turned to a drastic situation as the one-third was not fairly or evenly divided on a pro rata basis after the product has left the hands of manufacturers.

Hundreds of licensed traders were complaining that they were not getting anything like the one-third of their normal supply. In almost every town in the country there was a brewer agent, or rather purchasing agent. These purchasing agents were, in nearly all cases, retail vintners themselves, and they appeared to be withholding from their former retail customers the greater part of the one-third supply. The purchasing agents claimed they could distribute barrels of stout as they like, i.e. that they could give two or three-thirds to one customer, and one-sixth, one-twelfth, or none at all to another customer. According to Mr O’Mullane, although the liquor traffic was not State controlled it could be argued to be so virtually, owing to the operations of the Beer Restrictions Act as applied to the manufacturers.

For the purpose of protesting against the rationing and intentions of the Westminster Government with regard to the Irish brewing and distilling industries, a public meeting was held in Cork City Hall on Friday evening, 1 June 1917. Lord Mayor Thomas C Butterfield presided. The attendance was large drawing interested parties from the city and county. The proceedings were published on 4 June in the Cork Examiner. The Lord Mayor noted that the numbers affected by the rationing were impossible to calculate; “One could enumerate indefinitely the number of people who would be affected by those restrictions, such as the brewers, the brewery workers, the vintners and the assistants. As far as the workers were concerned, it was elementary knowledge that the men employed in breweries and distilleries or maltings were men who had spent most of their lives at their respective businesses, and if they were disemployed, they would be absolutely no use for anything else”.

The Lord Mayor outlined that vintners, for the most part, lived by the sale of liquor. Many of them had large families, and that it would be a crime if their means of livelihood was taken from them. The taxpayer, too, would be hard hit; “the revenue from the sale of liquor would be reduced, and this, deficit would have to be made up some way”. The farmers, too, would not have a market for their produce. “It the Government were determined to crush out the distilling and brewing trade in Ireland, they had a right to compensate the people for it”.

The City High Sheriff William O’Connor moved a resolution “calling on the Government to relax, or at least to modify, the restrictions at present in force with regard to the Irish brewing and distilling industries which were causing so much inconvenience, hardship and dissatisfaction to the general public, pointing out that such drastic curtailment, as far as Ireland was concerned, was not absolutely necessary”. Despite revealing himself as a teetotaler, he highlighted that what he wished to speak about at the meeting was “the injustice sought to be perpetrated on Ireland by the Government”. The City Sheriff noted that outside the shipbuilding industry in Belfast, British rule had left Ireland practically no other industry of any importance with the exception of the brewing and distilling industries.

The City Sheriff continued his concerns about the effects on the circa 520 public houses in Cork city, with its population of about 76,000—that was one public-house for every 150 persons. The Cork breweries employed around 500 men, and he had been informed that as consequence of the regulations of the Government one brewery discharged 70 men and at another brewery 30 men. He questioned the future employment prospects of those made redundant; “What was to become of these men – that was a point that deserved their most serious consideration. The licensed vintner?, the vast majority of whom were respectable men and women, had always contributed in a most generous manner to all charitable objects as well as to every movement for the betterment of the people and the country, and were those traders, after putting all their savings into their promises, to be thrown on the roadside?”. To him, the licensed vintners circulated a large amount of money and gave a good deal of employment, and he held that if they were to be treated in such a manner they should be given adequate and reasonable compensation.

Cllr Timothy Sheehy said they should demand of their members of Parliament to “strike a decisive blow in their cause”. He argued that for a century England had starved the industries of Ireland, and they were now going to continue that policy. He believed the meeting would have a great effect on the vital question of whether they were going “to allow Lloyd George and the Government crush out those great industries”. After several more passionate speeches, the motion was unanimously passed.

Captions:

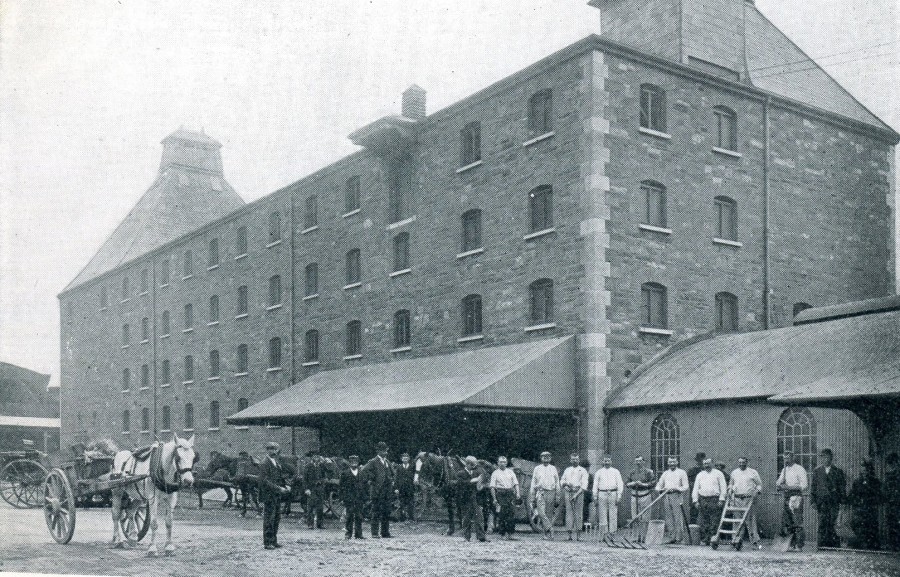

897a. Murphy’s Brewery, Blackpool, 1903 (source: Cork City Library)

897b. Malt house and yard, Murphy’s Brewery, Blackpool, 1903 (source: Cork City Library)

McCarthy: EU Structural Funds Retrofitting Cork’s Social Housing

Press Release

A recent report read at the Housing Strategic Policy Committee of Cork City Council reveals that Cork’s social housing is benefitting from European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

Independent Cllr Kieran McCarthy, a member of the Council’s housing functional committee, notes that there is a considerable stock of social housing in public ownership, generally in disadvantaged areas, which do not meet the new building requirements in terms of energy efficiency and performance.

“Currently the national social housing stock is comprised of some 130,000 rental properties, most of which are located in the country’s cities and towns. It is estimated that there are some 25,000 older properties with low levels of energy performance, due mainly through heat loss through the fabric of the building. With EU structural funds, targeted measures can be pursued to address improved energy efficiency, carbon savings, and improved comfort levels”, McCarthy highlighted.

“There are also large numbers of owner occupied non-Local Authority homes, which were constructed before 2006, where the energy efficiency and performance is very poor. A further targeted measure to address energy efficiency improvements in these homes, specifically targeting the elderly and vulnerable, making the homes more comfortable, healthier and more cost effective to run will also be rolled out. Ultimately these programmes also create an increase in green jobs in Ireland”.

“The level of ERDF or EU structural funds being invested in Cork and other counties is really significant and sometimes not acknowledge fully in the public realm. Focus is also being places on developing new technologies (ICT), small and medium- sized enterprises (SMEs) and an increased focus on sustainable urban development such as stronger transport mobility models”.

“A funding package of €500 million from the ERDF and the Irish exchequer is being invested in the region over the programme period 2014-2020. The ERDF aims to strengthen economic and social cohesion in the European Union by correcting imbalances between its regions”.

McCarthy: A Larger Marina Park should be Pursued

Press Release

Independent Cllr Kieran McCarthy has welcomed the site preparation phase for phase one of the Marina Park, which comprises new riverside public sports, adventure and ecology Park – all of which wraps around the new Pairc Ui Chaoimh. “The creation of Marina Park pursues a 170-year-old plan for the area to develop a park worthy of being named City Park, notes Cllr Kieran McCarthy.

Cllr McCarthy is the author of a publication on the history of the Munster Agricultural Society and gives historical walking tours of the Marina and surrounding suburbs.

“A larger municipal park was proposed in the area in the 1840s by Cork Corporation’s Engineering department. The reclamation of land behind the Navigation wall or dock now part of the Marina Walk was accelerated through the provision of the Atlantic Pond in the 1840s, the opening of the City Park racecourse in 1869, the new showgrounds in 1892, shortly followed by a GAA pitch at the turn of the twentieth century and the new ford Factory in 1917. It is now through European funding of e.4m that we can begin to pursue that dream even further and create a super public amenity in the area. In addition, such heritage DNA should also be remembered in the footprint of the park. I welcome that part of the old stands are to become part of Marina park”.

“There are also lessons to be learned from other parks in the city. Despite the circa e30m investment into the nearby 180-acre Tramore Valley park it remains closed due to staffing shortages and funding challenges in the Council. I don’t want to see a brand new Marina Park and then no funding available to staff it, maintain it or open it”.

“There is also the elephant in the room that there may be room to create an expanded Marina Park. With all of the development land of former Howard Holdings in NAMA, it remains to be seen how these lands will be developed. I have advocated that part of the South Docklands plan will have to be revisited and redesigned. It would be great to have an elongated Marina Park through whatever new plan emerges. Public amenity space needs to be at the heart of the emerging Docklands quarter”.