Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 7 December 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 7 December 2017

The Wheels of 1917: Housing Crisis Solutions, 1917

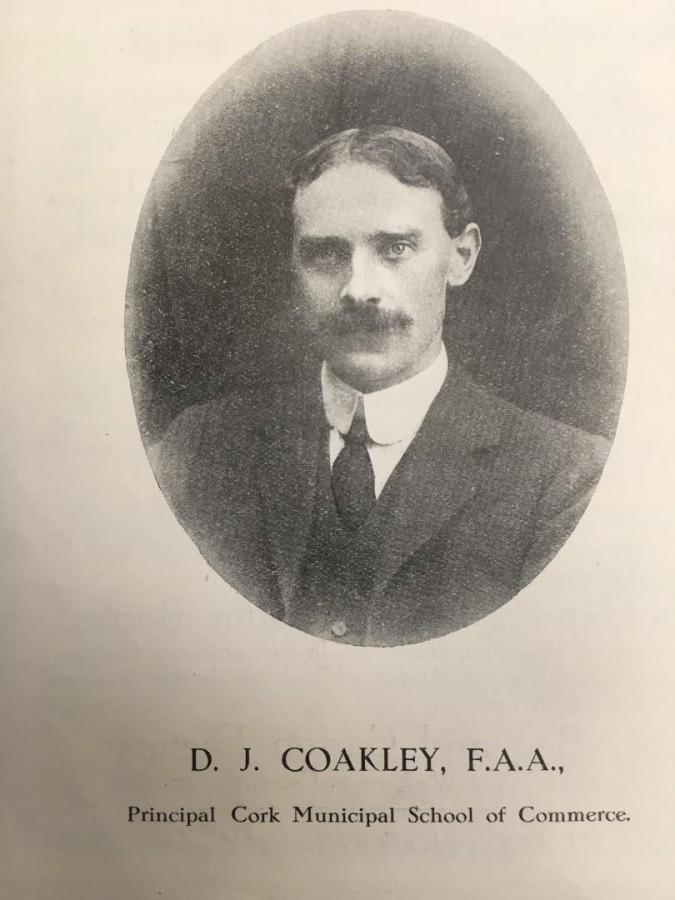

In the first week of December 1917, Mr D J Coakley, Principal of the Cork School of Commerce, delivered a lecture entitled General Principles of Housing and Town Planning, with a specific focus on Cork. His public lecture was delivered with the Cork Municipal School of Commerce in the lecture theatre of the School of Art. Many of the challenges Mr Coakley spoke about are still relevant in today’s city.

In his lecture, D J Coakley outlined that from the reports or the Medical Superintendent Officer of Health, the Corporation of Cork had during the previous thirty years expended £81,200 in clearing unhealthy and dilapidated areas, and providing some 532 houses and 11 houses of 33 flats for the “labouring classes”. Since 1906 Cork Corporation has spent over £51,000 in re-surfacing the streets. The question of widening certain streets had been under consideration and amongst others, improvements had been carried out at Friary Lane, French’s Quay, and Windmill Road. The Housing Committee of Cork Corporation had secured an option on two sites for housing, on the outskirts of the city at College Road and near Roches Buildings, and had asked for a Local Government Board Inquiry into a Housing Scheme for Cork.

D J Coakley highlighted his view that in 1917 houses were built more or less haphazard and without any proper formulated general plan. In his opinion nothing could be of more vital importance to any city than that of its people should live in “good quality accommodation with beautiful surroundings”. He noted: “there is no doubt that when the dreadful war was over, schemes of housing and town planning could then be undertaken in all large cities”. He detailed the Corporation of Cork had already taken some important steps. There was a special committee to deal with the housing question. and they consistently called for State grants to address the matter. A considerable amount of valuable information relative to the condition of housing in the city had been collected.

Mr Coakley painted a stark picture of housing stock in the city. There was a very large proportion of unsanitary houses, as he described, not quite suitable for human beings to live in”. In referring to the tenement houses he stated that some of them were so old and dilapidated, and so structurally bad. Hence repairing them was out of the question, and, consequently, almost forty houses were closed some years previously because of being unfit for human habitation. Coakley made the case that accommodation was urgently needed for 115 families, whose houses just needed be demolished as they were in such a poor state.

Mr Coakley stated that overcrowding was a large challenge. In 719 tenement houses 726 cases of overcrowding were discovered. ln some cases the cubic space of the sleeping apartments amounted to only 72 cubic feet for each person. There were several instances of where the father and mother, and sons and daughters over 20 years of age, all slept in the same small apartment. Of the 12,850 houses in Cork, 1,500 were unprovided with back yards and nearly half were situated in the centre on the flat of the city.

Lack of space rendered it impossible to keep even the smallest stock of commodities. Coal, oil, and other fuels were usually stored under the bed. Mr Coakley spoke about endless drudgery and breeding places of mental deterioration; “endless drudgery, such as taking water up four or five flights of stairs uses up all the energy of the mother who has neither time nor strength to give to the care of her children; from these breeding places of mental, moral, and physical deterioration emerge the work-shys and unemployables, born and bred in insanitary slums, with the gutter for a play-ground”.

In his conclusion Mr Coakley outlined a number of potential solutions. He was excited about the next steps to be taken to formulate a competition tor the best plan for the future development of the city. He wished to offer a prize sufficiently large to attract the very best brains in the subject of housing and town planning. Cork’s new Housing Schemes needed to be in the suburbs and landowners should be encouraged to develop their own estates. The question of co-partnership housing with private landlords was worthy of serious consideration. The rents of the poorer classes were not sufficient to enable houses to be built economically for them by private enterprise, and that, therefore, a State’s contribution was necessary in addition to a State loan. The Housing Committee of Cor Corporation was taking active steps to secure a State grant for Housing. Coakley also called for a joint housing and town planning committee to consider the housing question in its different aspects-social, economic, engineering and legal and to make surveys. A Cork Town Planning Association was founded in 1922 and the document Cork: A Civic Survey emerged in 1926. The survey can be viewed on the local studies website of Cork City Library on the Grand Parade, www.corkpastandpresent.ie or viewed in local studies in hard copy.

Secret Cork, which is my 2017 book, and published by Amberley Press, is now in Cork bookshops. For information on other publications check out www.corkheritage.ie

Captions:

924a. D J Coakley, Principal, Cork School of Commerce, c.1917 (source: Cork City Library)

924b. Section of slum area to the south west of St Finbarre’s Cathedral; twenty acres of which was demolished in the early 1930s to make way for Cork Corporation’s social housing scheme (source: Cork City Library)

Cork City and County Councils, Boundary Extension Proposal, 5 December 2017

The latest in a series of engagements between the two Cork Councils and the Implementation Oversight Group (IOG) took place yesterday (Monday 4th December 2017), with political and executive representatives from both sides meeting with the IOG. The elected members of both Councils were subsequently briefed in relation to progress made on agreeing a boundary alteration.

It is understood that the Chair of the IOG, John O’Connor, will this week deliver his report defining a revised city boundary to the Minister for Housing, Planning and Local Government, Eoghan Murphy who established the IOG.

Lord Mayor, Cllr Tony Fitzgerald described the outcome of yesterday’s engagement as positive. “The scale of the boundary extension discussed yesterday represents a significant reduction in the boundary originally proposed by Cork City Council to the Cork Local Government Review Group. However the City Council has engaged fully with the IOG in its efforts to deliver a deal that could form the basis of the expansion of the city,” said the Lord Mayor.

“The process has been protracted and complex and the compromise proposal hasn’t met with all our expectations. However it represents a historic opportunity for Cork – both for the City and County, and indeed the wider Cork region. Working together, both Councils can grow Cork to be a true counter-balance to Dublin and help to drive the national economy”, he said.

County Mayor, Cllr Declan Hurley, expressed his satisfaction that both sides have achieved considerable progress.

“Both Councils have invested significant time and effort in recent weeks in reaching a solution, and the fact that a proposal has been identified is testament to the desire on the part of both Councils to conclude the matter locally. Everyone involved has adopted the approach that any boundary alteration must deliver what is best for Cork, its people, its communities, its future. While Cork County Council is ceding significant territory to the city, it will continue to retain responsibility for a large portion of its overall strategic employment areas (for example, areas such as those surrounding the entire Cork Harbour, Little Island, and East Cork, will remain in the county). Both Councils acknowledged that it was unlikely that they would each achieve all that they individually sought to achieve. Today’s developments provide a solid basis to move forward – on a joint collaborative basis – to drive the entire city and county of Cork as the leading economic region outside of Dublin, and that is great news for Cork”.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 30 November 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 30 November 2017

The Wheels of 1917: Legacies of the Manchester Martyrs

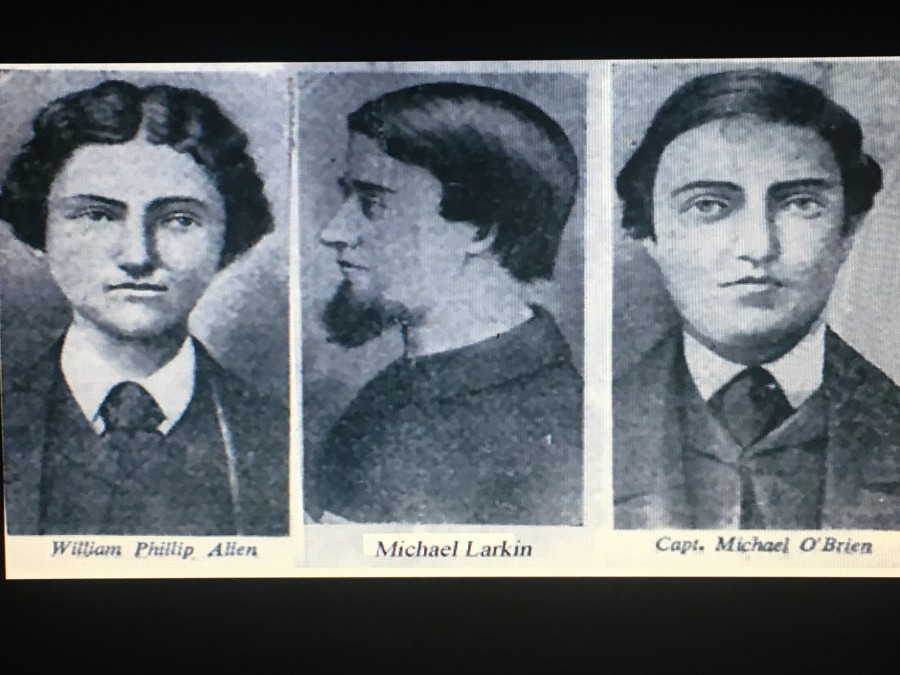

This week marks the 150th anniversary of the Manchester Martyrs – they were William Allen, Michael Larkin and Michael O’Brien, all born in Ireland but living in Manchester and active Fenians. In 1867, after a most unconvincing trial, they were executed for their part in a successful ambush to free two Fenian leaders from a prison van in which a policeman Sergeant Brett was shot dead.

One hundred years ago, on Sunday 26 November 1917 the fiftieth anniversary of the Manchester Martyrs was celebrated in Cork by Sinn Fein and the re-organised Volunteer battalions. a public procession through the principal sheets of the city and a meeting at the National Monument, Grand Parade. The procession was an impressive one, and the route was through North Main Street, North Gate Bridge, Pope’s quay, Bridge Street, King Street, Brian Boru Street and bridge, Merchant’s Quay, St Patrick street, and Grand Parade. The Volunteer Cycle Corps was in the front, then came the, Pipers’ Band, followed by the Irish Volunteers, the Cork Workingmen’s Brass and Reed Prize Band. When the different contingents reached the National Monument, orations were delivered, which compared the IRB / Fenian movement with the ongoing Independence campaign in the post 1916 era.

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) was founded in Dublin and New York in 1858. The founders included James Stephens, John O’Mahony, Charles Kickham, John O’Leary, Thomas Clarke and Michael Doheny, all of whom had been connected in a post-famine rising in 1848. In addition, Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa established his Phoenix Society at Skibbereen, County Cork. The belief of the IRB or later to become known as the Fenians was similar to that of the ideas of Thomas Davis on Irish nationality, and they also believed that Britain would never concede independence without the use of physical force. Their central focus was to concentrate on the independence of Ireland from Britain. The followers of this organisation were primarily working men, in particular small farmers. By 1867, thousands of such persons had enrolled and preparing themselves for action.

On 5 March 1867, risings took place in Dublin, Cork and Limerick, On the night of Shrove Tuesday, 5 March 1867, over 2,000 Fenians in Cork City were ready for action. The rallying point was at Limerick Junction and the Cork Fenians were to meet with forces from Kerry and from Mallow and surrounding areas in North Cork. With not that many weapons between the groups as a whole, it was planned to raid private houses and barracks for guns and ammunition and hope that munition shiploads would arrive from the USA in Cork. However, the plan was not to be that straight forward. Cork weather in the form of a blizzard and high resistance among munition stations hampered the quickness of an attack. Thus, instead of advancing, the Fenians were forced to retreat with the eventual order being given to disperse.

The rising had failed and in the days following the event, a large force of marines were drafted in from Southampton to Cork; Victoria Barracks (now Collins Barracks), Elizabeth Fort and Cat Fort were reputed to be filled to capacity with troops. These militia men were to patrol the streets of the city by day and by night. Involvement in this rising was to result in arrest and the local newspapers of the time, the Cork Examiner, Cork Constitution, the Cork Herald and the Southern Reporter carried daily reports of these latter arrests

On 11 September 1867, Colonel Thomas J Kelly (Deputy Central Organizer of the Irish Republic) was arrested in Manchester, where he had gone from Dublin to attend a council of the English ‘centres’ (organisers), together with a companion, Captain Timothy Deasy. A plot to rescue these prisoners was hatched by Edward O’Meagher Condon with other Manchester Fenians. On 18 September, while Kelly and Deasy were being conveyed through the city from the courthouse, the prison van was attacked by Fenians armed with revolvers, and in the scuffle Police Sergeant Charles Brett, who was seated inside the van, was shot dead. The three Fenians, who were later executed, were remembered as the Manchester Martyrs.

On the same day as the executions in November 1867, Richard O’Sullivan Burke, who had been employed by the Fenians to purchase arms in Birmingham, was arrested and imprisoned in Clerkenwell Prison in London. In December, whilst he was awaiting trial a wall of the prison was blown down by gunpowder in order to affect his escape. The explosion caused the death of twelve people, and injured one hundred and twenty others. A week later the Foaty Bay Martello Tower in Cork Harbour was attacked by Fenian members on St Stephen’s Night, 1867. William Lomassaney O’Connell from Passage West with an alias of Captain Mackey led the attack. The tower garrison consisted of two gunners of the Royal Artillery. He and other members took a number of eight-pound cartridges, variously stated from ten to twenty, besides a quantity of fuse. After staying for some time, they left the tower, to which it is supposed they had come to in boats. William Lomassaney was a wanted man by the police for the raid on the Martello Tower. He was arrested with two of his accomplices at Cronin’s public house in Cornmarket Street, Cork on 7 February 1868.

Captions:

923a. Depiction of Manchester Martyrs 1867 (source: Cork City Library)

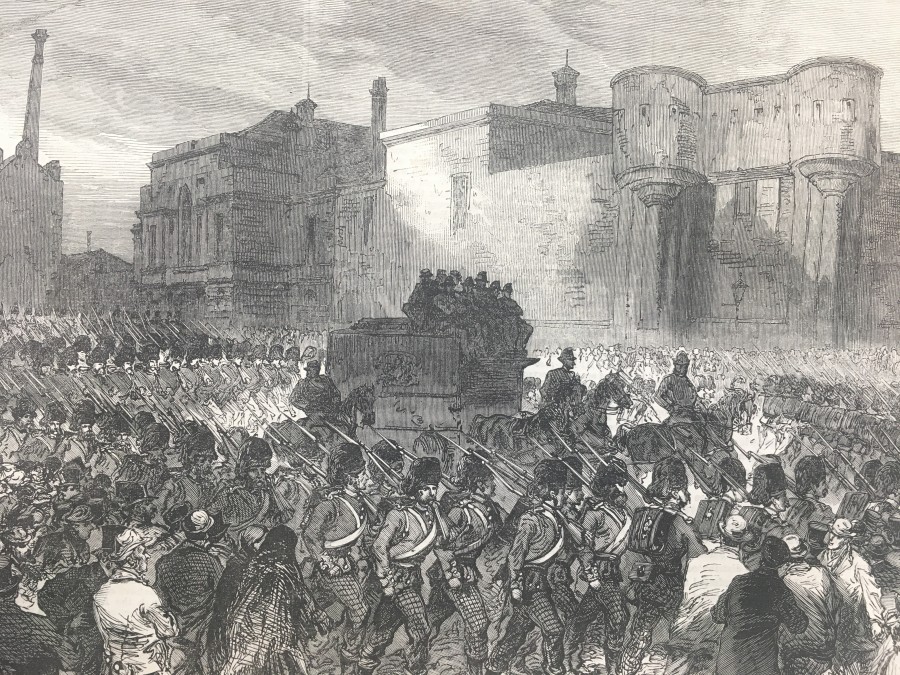

923b. Prisoners leaving the new Bailey for the Assize Court, Illustrated London News, November 1867 (source: Cork City Library)

Ballinlough Christmas Concert, Sunday 3 December 2017

Always a great evening’s entertainment!

Kieran’s Question to CE, Cork City Council Meeting, 27 November 2017

Question to CE:

To ask the CE, as the south docks area develops in the Navigation House area, what plans and measures are in place to reduce the increasing congestion of traffic in the morning and evening times? (Cllr Kieran McCarthy)

Motions:

That the City Council provide better pedestrian priority measures as Boreenmanna Road meets Rockboro School; the visibility of the traffic lights and luminous areas needs to be improved as do widening the footpaths from the school to Castlegreina Park (Cllr Kieran McCarthy)

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 23 November 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 23 November 2017

The Wheels of 1917: Games of Cat and Mouse

One hundred years ago, on 16 November 1917, Terence MacSwiney was court martialed in Cork for wearing an Irish Republican Army (IRA) uniform and drilling and training volunteers on 21 October 1917. Terence’s arrest was part of Westminster’s Defence Against the Realm Regulations. It was part of the rounding up of forty-seven Sinn Féin officers who were openly drilling, training, parading and wearing uniforms. The arrested men were from Cork, Kerry and Limerick and were lodged in Cork County Gaol, next to University College Cork.

Prohibitions against drilling, wearing uniform, carrying arms or even hurleys, had been announced by the British authorities. The first public challenge to these restrictions on a national scale was made by Sinn Féin in October 1917. On Sunday 21 October public parades were held all over the country in honour of Thomas Ashe who had died on hunger strike in Mountjoy Gaol, Dublin on the previous 25 September.

Terence MacSwiney organised a public parade of the two city battalions. Battalions mustered several hundred men outside their closed hall in Sheares Street and marched via Lee Road to Blamey and back again to the city. Tomás MacCurtain led the recitation of the rosary at the National Monument at the conclusion of the parade. Tomás MacCurtain, Terence MacSwiney and the officers were subsequently arrested.

According to the recorded proceedings of the court martial trial on 16 November 1917, Terence MacSwiney did not answer when called upon, and subsequently answered in Irish. Asked if he found any objection to being tried by the Court, he again replied in Irish, and the President of the court martial session noted that if he did not answer in English he would be committed for contempt. Terence repeated his observation. Evidence was then given to drilling at Mount Desert by a party of about 500 men who subsequently marched through the city. Tomás MacCurtain and the other five prisoners adopted a similar approach to that of Terence MacSwiney in speaking in Irish. The companions included John O’Sullivan (Abbey Street), Frederick Murray (Sunday’s Well Road), John Murphy (Friar’s Walk), Christopher O’Gorman (O’Connell Street), and Patrick Higgins (Dominick Street). Each were sentenced by the court to one year-imprisonment without hard labour.

Terence MacSwiney went on a hunger strike for three days prior to his release. He was rearrested four months later to complete his sentence. Terence’s internment in March 1918 caused him to miss two major life events – the birth of his daughter, Máire, in June, and his election to the first Dáil as TD for Mid Cork, in December. Released in Spring 1919, he took his seat.

In 1916 there were a handful of hunger strikes, contesting punishments imposed by the prison authorities. The technique was adopted in earnest in 1917. Forty prisoners on hunger strike were forcibly fed, and this procedure killed Thomas Ashe. Originally from Kerry and a teacher by profession, Thomas Ashe was a prominent activist in most of the major nationalist organisations of the pre-independence period, including the Gaelic League, the Gaelic Athletic Association, the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and the Irish Volunteers. Ashe was responsible for leading the Irish Volunteers at the battle of Ashbourne in County Meath, the most significant military engagement outside Dublin during the Easter Rising. He became a key figure in the reorganisation of republicanism in 1917. Thomas Ashe was arrested in August 1917 and charged with sedition for a speech that he made in Ballinalee, County Longford. He was sentenced to two years hard labour.

Whilst in Mountjoy Gaol, Thomas Ashe (32) and other prisoners demanded prisoner of war status instead of that of ordinary criminal. As a result of prison staff taking away their beds, bedclothes and possessions, they went on hunger strike on 20 September 1917. Forcible feeding began on 23 September. When Thomas Ashe was forcibly fed and immediately collapsed afterwards. He was transferred to hospital where his condition continued to deteriorate, and he passed away.

Over the next two and a half years, hundreds of prisoners went on hunger strike; almost all gained concessions and often release. This strategy was release and re-arrest, legalised by the ‘Cat and Mouse’ (Prisoner’s Temporary Discharge of Ill Health) Act of 1913. It had been utilised with some success against the suffragettes. Under the Act, the hunger striker would be released when their condition had deteriorated considerably; when she had recovered her health, they served the rest of their sentence. In practice, released prisoners were re-arrested only if they participated in militant protest. The Act proved effective by deterring the activities of leading militants—if not in prison, they were either physically incapacitated or preoccupied with escaping recapture.

There are many examples of the above Cat and Mouse Act revealed across newspapers such as the Cork Examiner. For example, four Dunmanway men – Messrs O’Mahony. McCarthy, Ahern and O’Neill, who had been released from Cork County Gaol and their hunger strike on 17 October 1917 were re-arrested on Thursday 6 November. They resumed the hunger strike, refusing to take any food in the prison. Another example took place on Monday morning at 7am, 19 November when sixteen prisoners, just tried by court martial for offences were removed from Cork County Gaol and taken to Dundalk prison. Whilst the deportation went on, from noon on that day approximately twenty prisoners who had been court martialled and jailed in Cork County Gaol over the previous weekend in consequence of their demands to be recognised as political prisoners went on hunger strike.

Secret Cork, which is my 2017 book and published by Amberley Press, is now in Cork bookshops.

Captions:

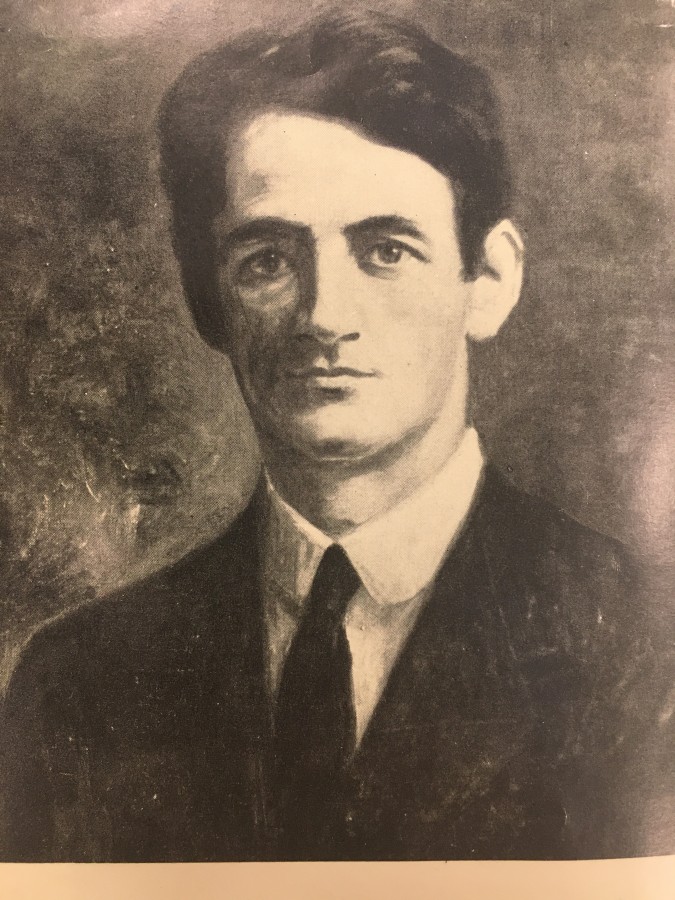

922a. Depiction of Terence MacSwiney, 1910s (source: Cork City Library)

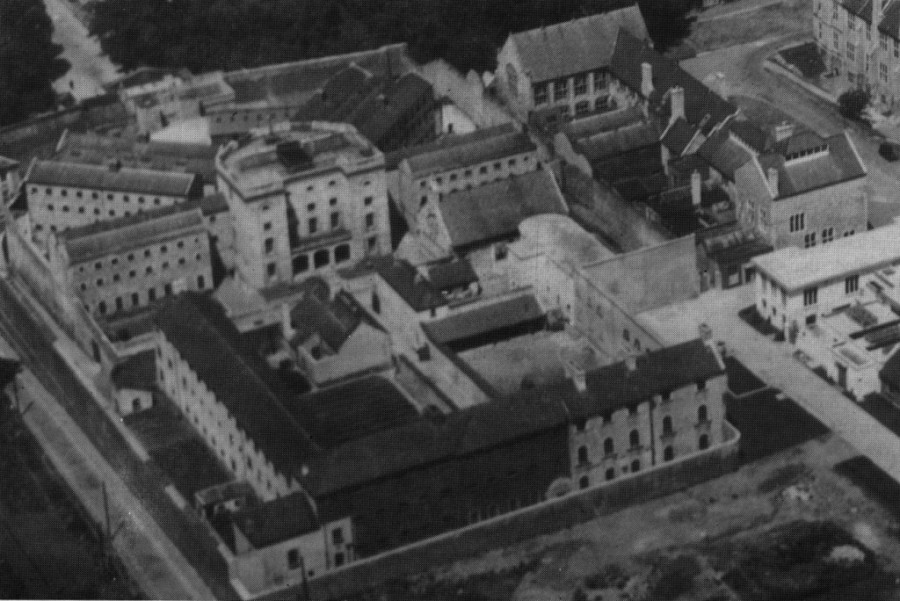

922b. Cork County Gaol adjacent UCC, c.1920; it is now the site of the Kane Science Building. Only the entrance portico has survived. (source: Cork City Library)

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 16 November 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 16 November 2017

The Wheels of 1917: The Demise of the SS Ardmore