Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 13 January 2022

Journeys to a Free State: A Treaty is Ratified

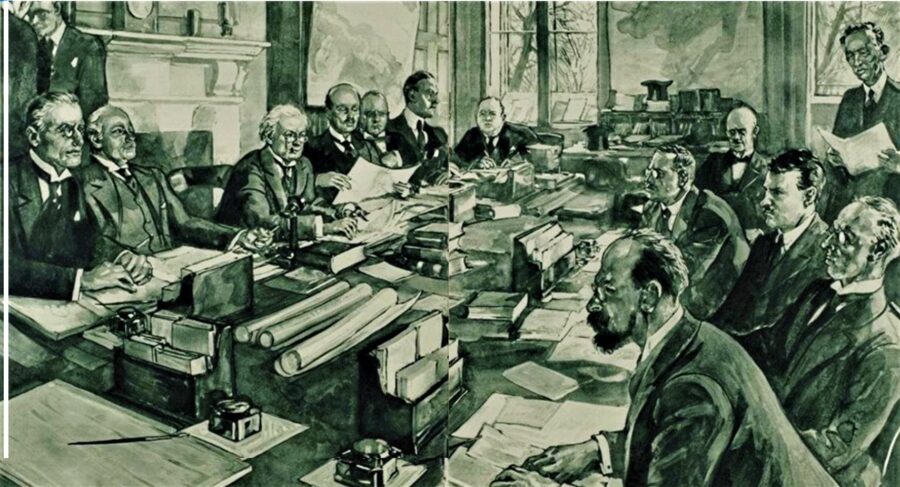

At ten minutes to 9pm on Saturday night, 7 January 1922, Dáil Éireann voted on the Articles of Agreement or peace treaty. It was ratified by 64 votes to 57. The division followed days of animated debate with the closing speakers being Cathal Brugha and Arthur Griffith. A total of 121 TDs out of 129 deputies recorded their votes. Out of the eight whose vote was not recorded five held dual representation to seats. One was the speaker, Eoin MacNeill who did not vote as his role would have been in a casting vote position. Just two deputies were technically unable to be present – one had expressed an opposing view on the Treaty and the other was in support – in their correspondence respectively.

The Cork Examiner records that each deputy of TD was allocated one vote. Some surprises arose during the polling, and it was evident that some deputies maintained secrecy as to how they would vote until they actually cast their vote vocally. When the decision of the assembly had been announced, the atmosphere again became electric, especially when President de Valera rose in his place, and made a speech, indicating that because of the verdict he would resign his office as Chief of the Executive of Dáil Éireann. He, however, had only concluded, when Michael Collins rose, and appealed for unity.

Cork’s Mary MacSwiney followed and in a short speech pointed out that they “could not unite the ideal of a Republic and a betrayal worse than Castlereagh’s [a reference to Viscount Castlereagh in LondonDerry]”. Her incisive comments again electrified the atmosphere. Mary had also given a long and passionate intervention against the Treaty in the days before the vote. De Valera again rose and announced that he would hold a meeting of his supporters on the following day at Dublin’s Mansion House. Another appeal for unity was made by Michael Collins as the assembly anxiously awaited the outcome of such interchanges.

The Cork Examiner records that De Valera again arose and in a very subdued voice said; “Before we rise I should like to say my last word” – but he only added one more sentence when he broke down, and resuming his seats placed his head between his hands resting on the table at which he thought for a moment. that for a moment it was the most intense scene, and it was only ended by the speaker’s announcement that the house would be adjourned until the subsequent Monday morning.

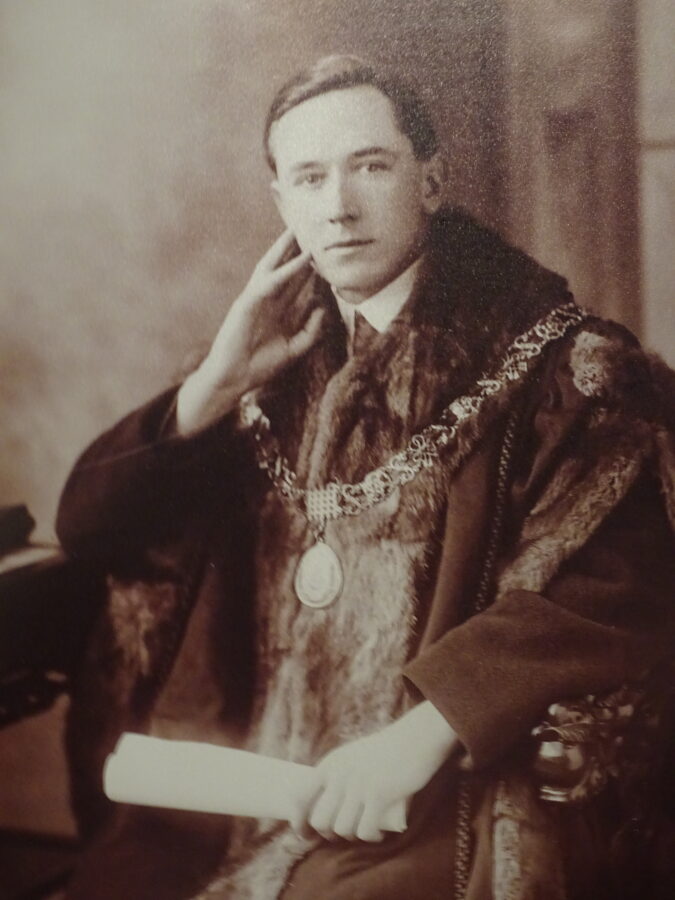

At that stage the Lord Mayor of Dublin Laurence O’Neil approached De Valera, took him by the arm and escorted him from the chamber. Deputies also departed and were followed by the public, with the result that the entire chamber was soon completely deserted. Along the corridors of the building many people, who were unable to gain admission to the chamber had congregated, while outside the university there was an immense gathering – each assemblage being most anxious to learn the decision of Dáil Éireann’s ratification question.

Outside the bulk of the public present appeared to approve of the action had been taken. Arthur Griffith was one of the first leaders is to leave in company with several of his supporters. He was the recipient of a great ovation especially when he made his appearance outside the main entrance to the vote venue at Dublin’s University Buildings, Earlsfort Terrace.

Shortly afterwards De Valera took his departure and cheers were called for him. Similarly, cheers were extended to Michael Collins, who had great difficulty moving through the crowds to get to his motor car. No interviews were given to the press by De Valera or Collins at that point.

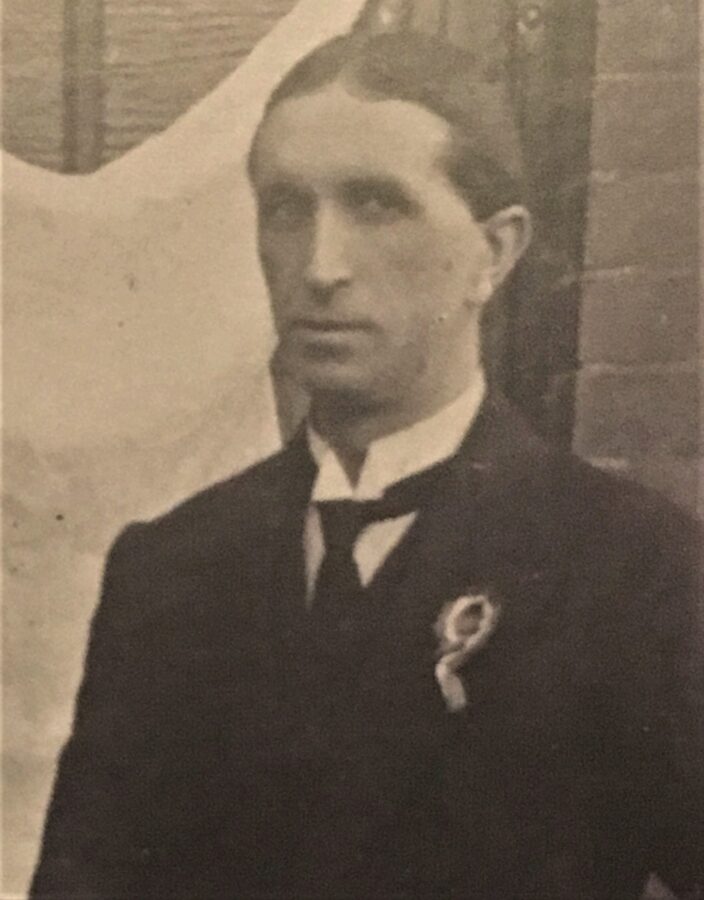

An interview was, however, given by the Lord Mayor of Cork, Donal Óg O’Callaghan. The Cork Examiner records that the Lord Mayor commented on the need to revisit the vote in the weeks ahead and made a call out for the public to remain calm: “Now that the decision has been given, there has been a terrible strain upon all participating in this debate. The forces at work were very strong. Personally, I deplore the decision. I think a great mistake has been made but I have the most profound confidence in my fellow country men and women, and I am satisfied that they desire absolute freedom now as fervently as ever – so for the moment they may desire the ratification of this treaty, owing to obvious circumstances and warweariness, and so on. That they never will be satisfied until what has been temporally undone tonight will be again established. I am firmly convinced that the aspiration of the Irish people will never be satisfied until the Irish Republic functions are recognised and unfettered.

Concluding the Lord Mayor offered some words of warning about maintaining discipline to the cause of the Irish Republic; “I hope the people of the country, and especially my fellow citizens in Cork will not allow the splendid discipline which has been our mainstay up to the present, and which alone enabled us to succeed as far as he did succeed, will continue on unimpaired, and that no acts, even of an isolated character will occur that might prove the starting point of a departure from this discipline which once lost could be regained only after much difficulty and after much loss. That discipline is no more than ever necessary if our country is not to be thrown into chaos”.

Back in Cork on Cork’s St Patrick’s Street the feeling of tension gradually increased as the evening wore on. From 7pm on large crowds of people congregated outside the Cork Examiner office waiting for the result of the vote.

The momentous news did not reach Cork till after 9pm, and its publication in a special extra edition of the Evening Echo gave rise to those waiting patiently for news on St Patrick’s Street. Within theatres and picture houses the news was relayed. At a packed Cork Opera House, comedians Iky and Will Scott, whilst performing during their introductory dialogue at their pantomime noted that “there was good news for Ireland”. Both shook hands on the stage. After announcing the ratification majority there was sustained and loud applause. Enthusiastic scenes were also witnessed at the Palace Theatre and at the picture houses, where the news had also been telephoned, and was promptly screened.

Missed one of the 51 columns in 2021, check out the indices at Kieran’s heritage website, www.corkheritage.ie

Caption:

1133a. Picture from the Treaty debate, Dublin, early January 1922 (picture: National Library of Ireland).