A Return to a Safe Harbour

Dear colleagues, Dear Chief Executive,

As outgoing Lord Mayor of Cork, a very warm welcome to the historic 1936 Council Chamber. A very warm welcome to those who have been re-elected and to those who this is your first time being an elected member of Cork City Council.

We also remember those who retired and those who didn’t make it back through the recent gruelling local elections.

And of course, one of the core parts of our AGM is to appoint our Council chair or the Lord Mayor.

And it will fall to me very shortly to take names of candidates interested in becoming Lord Mayor of Cork for the following year and to pass this eighteenth century chain of history to its next guardian so to speak.

I have but three very short reflections before we proceed.

Firstly, dear colleagues let us rejoice that the democratic process is very much alive in Cork.

My dear colleagues you have not only walked 1000s of kilometres in your quest or pilgrimage to take one of the 31 seats. You have gone to suburbia and into the inner city, and knocked on 1,000s of doors.

You have sacrificed your personal lives in a quest to be in the service of the people of Cork in local government.

It is also important to reflect on that pilgrimage that the process is not as easy as just walking and knocking on doors.

You must have belief in your message. It is a leap of faith. You have been tested. You had to be fit physically and more importantly emotionally.

You met people who befriended you straight away. You met people who closed the door in your face. You met people who had their own message.

You met people who are happy, who are sad, who are very angry, who shout in your face, who don’t want to talk, who are struggling in life, who seek a listener, who seek a chance, who are soaring in life, who buried a loved one, an hour before you called, a mother who just put their child to sleep, people who will ask you in for tea.

You encountered opinionated people and people who have no opinion,

people who are the salt of the earth, people who are guardian angels,

people who you perhaps wept for in your private moments,

people who you laughed with, people who invited you into their house to chat about this and that.

You have met survivors. You have met people who have given up on life. You met people who are lighthouses. Plus many more.

You are a pilgrim of sorts.

All of the conversations, debates and empathy with 1,000s of constituents or citizens and that personal connection piece makes Irish democracy one that is very important.

You have not only rang doorbells and physically pressed the flesh so to speak but deep dived down into citizen life listening to their concerns and now being able through your election as an elected member to bring these concerns into the historic Council Chamber here and to the wider City Hall.

We should never take democracy for granted especially in the world we live in today and that in some parts of the world there is no democracy.

A sincere thanks to all those who voted two weeks ago.

We as local politicians saw another part of the democratic process close up when it comes to counting the votes on ballot papers. The solid count process we have in Ireland and what we have witnessed in Cork is one to be heralded, be proud of and one where great credit is due to the Office of Corporate Affairs and the Office of Franchise in Cork.

And so my first message this evening is a nod on the importance of the canvass pilgrimage of sorts, the democratic process and one of thanks to you, our Council staff and especially to the citizens of our historic city who came out to support our recent local election and its democratic processes.

My second message to you concerns my year as Lord Mayor. Fifty-two weeks ago, the elected Council of the last Council term entrusted me with leadership of the Council.

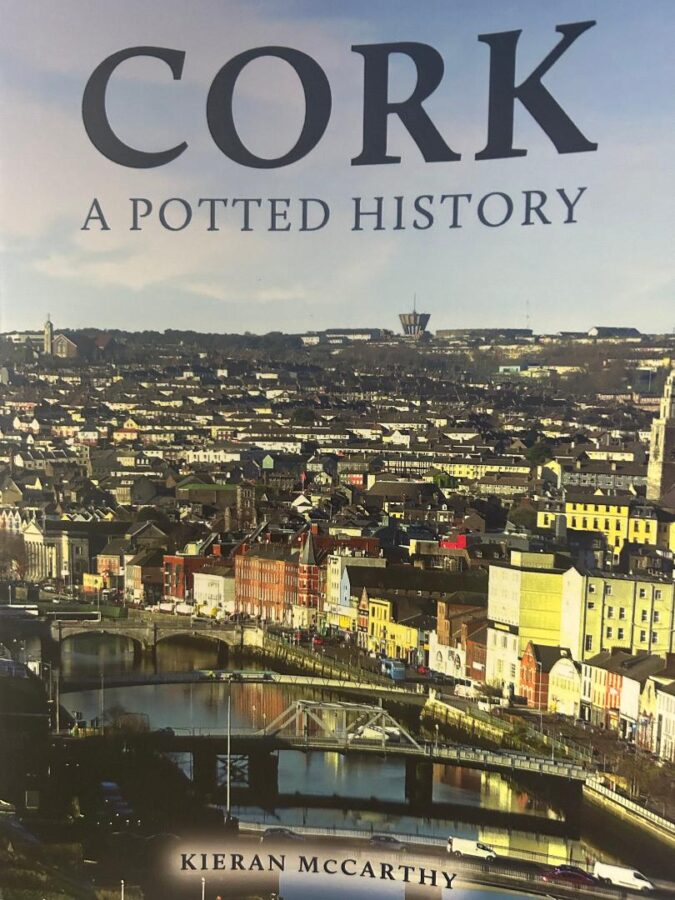

That has been a really deep honour and it is one thing writing about Cork history, it is another being a part of it. Indeed, it is very difficult to sum up my experiences in a few sentences.

Looking at the diary since the last Cork City Council AGM in late June last year I have been engaged with over 1,600 events. On average there have been about 30-40 events a week depending on the season.

The days have been long and the diary has been very demanding but to get to explore Cork and many of its stories has been very fulfilling. One day can feel like three days when there are so many diary events to juggle!

One hour one could be at a presentation of cheques, or the presentation of certs, and the next you journey on and could be praising someone for their sporting achievement or helping open a new business, meeting an ambassador or giving a talk at one of Cork’s 118 schools or giving a tour of the Lord Mayor’s Office to various community groups.

All of these events look forward and build a sense of identity for Cork’s future. Some events have been varied ranging from a one person engagement to thousands of people. And of course, many of you popped up in the story boards as well to offer support.

However, across all of the events the common denominator has always been Cork. There are thousands of people in Cork engaged in not only its life and its story but enhancing its life and story. Every hour of everyday someone is doing something great for Cork and its communities.

Much of it goes without being seen but the office of Lord Mayor’s gets to what I call “deep dive” down into many stories and moments. In our city such stories matter or indeed such moments need to be cherished.

The sense of togetherness, stories and moments in Cork I have promoted and spoken at length about all year.

In particular I have harnessed the city’s coat of arms as a message – the two towers and the ship in between and the Latin inscription – Statio Bene Fida Carinis – or translated “a safe harbour for ships”. Whereas the element of shipping has almost moved from the city’s quays, the inscription could also be re-interpreted as a connection to people – that the city is also a safe harbour for people and community life. This is its greatest story and one the City needs to mind, keep vibrant, and for all of us in this historic and innovative city to keep working on.

But during this second message of the importance of stories and togetherness it also falls to me tosincerely thank the Deputy Lord Mayor Cllr Colette Finn for her expertise, support, positiveness and I would like to wish her well for the future,

the Lady Mayoress Marcelline for her patience, support and love, and for her charity work, singing and dancing and all round community building with different groups,

and to my parents, and siblings and wider family members for their support and love.

A sincere thanks to Finbarr Archer, Nicola O’Sullivan, Rose Fahy and Caroline Martin in the Lord Mayor’s office as well as the team in Corporate Affairs ably led by Paul Moynihan with support by Alma Murnane and Nuala Stewart – without such a team the office would not run effectively as it does but it is filled with people – a team – that really cares about the role of the office in our city and all the nuances attached to such a role

and also a sincere thanks to you Chief Executive Anne [Doherty], for your friendship, partnership, curation of activities, story board creation, support and advice over the past year. And I am very conscious that this is your last AGM, so many thanks for all your work.

My dear friends, let me conclude with my third message and if I am going to go down as the singing Lord Mayor let me end my Mayoralty where I started with a verse by Rogers and Hammerstein, which in its own way became a different kind of anthem during the year,

Oh, what a beautiful morning,

oh, what a beautiful day,

I got a beautiful feeling everything’s going Cork’s way,

eh, Oh what a beautiful Day.

Go raibh míle maith agaibh.

Ends.