Category Archives: Cork History

Farewell to the Lord Mayor, 16 June 2017

Sailing on a Sea of Positivity

Kieran’s Comments, Cork City Council AGM, 16 June 2017

Congrats on a great year – sometime during this week, a news reporter noted that you have been a “tremendous ambassador for Cork”, which is true to say.

Positivity as a theme has a very worthwhile ship to steer – it is one which many people could get behind and steer – and one where people naturally gravitate to.

Positivity is one that this city more and more needs to address inward looking and outward looking – there are challenge yes – there are problems – but in this city’s ship there are many cabins, crew members, different leaders– there are ship’s ropes that one can get entangled in and stuck in – but also ropes when dusted off, pulled taut, can lead to an amazing set of sails to ride the crests of wild raging storms.

One would be hard pressed to find a community within the city’s boundaries and in its outliers that doesn’t have a strong sense of place and identity – where building community capacity, family nest building, ambition and creating opportunities matter, and when compiled create a very strong Cork Inc.

The narrative of Cork Inc was one your ship also embraced -where ever you travelled the importance of the identity and identities created over time through the lens of this ancient port city prevailed your speeches.

Identity does play on the imagination, personal, collective and civic in Cork; it interconnects between spaces and times into our present and future engaging memories to flow and bend across the story of the development of this north Atlantic big hearted small city.

The medallion on the Mayoral chain, which you clearly wore proudly this year, I always feel embraces that sense of openness as well – the city’s coat of arms – the two towers of King’s and Queen’s Castle and the ship in between with the Latin inscription, Statio Bene Fida Carinis, or A Safe Harbour for Ships.

The portcullis, the symbol of a gate, which once lifted to leave ships in to dock into Cork’s walled town – to a small harbour, with creaking stone walls as well as creating timber ships – Each arriving ship would have brought a sense of wonder and acknowledgment in the city’s role in maritime western Europe – and no doubt creating an orchestra of materials, river, dock and sea – enough to force the dock workers, business people, sailors and captains to speak loudly and more assertively above the orchestra of the docks to transact their business.

One of the many defining features of your year was to give voice to the busy flotillas of the city’s ships of business. In a Council where we depend on the goodwill and trust of the business community, it has been enlightening to see your small business award schemes being floated giving voice to very hard-working business owners.

It has been enlightening from a local history context to hear about businesses whose roots go back far in the city through recessions and oppressions, wars and destruction to transformations and boom, development and re-starts. Indeed, it is true to say that what you shone a light upon is an unexplored heritage, which needs to continue to be minded and elaborated upon.

Ultimately what your ship of positivity has championed is that there are many corners in the city that are proud of their identity, are willing to take on the winds of challenges as they come.

Thanks again.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 15 June 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 15 June 2017

The Wheels of 1917: The Complexities of the Cork Union House

The history of the Cork Union workhouse on Douglas Road is well documented (now the site of St Finbarr’s Hospital). The archives of the Cork Board of Guardians in Cork City and County archives are extensive, and include a large numbers of minute books, that record the proceedings of the Board’s meetings, 1841 – 1924. Many subjects are recorded in the minute books, such as the ongoing struggle to both fund, staff and manage the workhouse and related services, attitudes to poverty, developments in public health provision, and the care of the infirm, the destitute, children, and the mentally ill. Such subjects are also fleshed out and debated in Cork newspapers of the day, such as the Cork Examiner, which published the minutes of meetings as far back as 1841.

Continuing the thread of exploring life in Cork one hundred years ago, like many other institutions in the city, the year 1917 for the Cork Union House coincided with continued cuts to service provision due the ongoing war. The old workhouse site provided an array of public services from accommodation, food, schools and hospitals. By 1917 the term workhouse had been renamed Cork District Hospital. At a special meeting of the Board of Guardians on 15 January 1917 salaries and cutbacks were outlined. There were men in their employment who were working for less than labourer wages. Urgent repairs were only to be pursued. The price of food was at such a level that a further increase made securing such goods prohibitive for relief. In January 1917, the provision of tobacco or snuff was to be minimised. It was proposed that milk be substituted for eggs. The consumption of coal in the institution was deemed too high with the cost in the summer the same as in winter. The butter bill was an enormous one. Other public boards had substituted margarine. As to the scarcity of sugar, they proposed to utilise condensed milk to sweeten teas. Attention was brought to the question of the three distinct lines of telephones in the institution– and that one ought to be suffice.

At the meeting of the Visiting Committee on 2 May 1917 officials spoke about being refused a war bonus because they were receiving rations. The meeting saw further cuts in rations. Unmarrried officials were to be cut but the difference made up in cash to them. Two shillings per week more were paid to dispensary porters. At 16 May meeting, the engineer’s report, which was read, highlighted that the cost of building materials had increased fifty per cent and timber was coming in 100 per cent dearer. It was impossible to fully carry out the ordinary repair work needed with a small staff contingent of seven painters and two masons.

In mid-May, the figures in the media revealed a large operation programme and the debate at meetings gives insights into the scope of the Union House and its complex. There were 1,450 people in the House (102 less than the figure for 1916). In the hospital, there was 980 patients in the hospital (45 less than the figure for 1916). The deaths during the week ended 5 May amounted to ten. The numbers of persons in receipt of outdoor relief totalled 1925. The daily supply of milk required totalled 182 gallons. It was bought from two sources – Mrs Hannah Forrest of Clogheen and Mr F Bradley of Carrigrohane. The tender of James Murphy of Nicholas’ Well for ten pigs at £112 was accepted. The wages of the bakers in the house were increased to the standard operating in the city, as were those of the carpenters and the fireman of the house. At the mid May committee meeting, the Ladies Boarding Committee was proposed to be dissolved – it had been established 30 years ago for the specific purpose of looking after young women with regards to giving them access to the site and improving their health.

At the Board of Guardians meeting on 29 June 1917, complaints were read from the Federation of Trade Unions of Cork and District Health Insurance Society as to two of its members and the treatment they received as patients. It was acknowledged that there was a prolonged delay at the porter’s lodge with formalities and restrictions. A custom existed that all patients had to undress at the lodge All no matter what they were suffering from were to seen by the medical officers. Deputy attendants was deemed not conducive to the sympathetic treatment of patients in the hospital. The shortcut solution for many years was to propose the appointment of paid attendants but the expenditure was high so probationer nurses were appointed.

At a Board of Guardians meeting on 21 September 1917, further insights are revealed. The Clerk of the Cork Union was manager of the schools – the number of girls in the female school was 51 whilst the teachers numbered 5. In the boy’s school there were 41 pupils and 3 teachers. In the Fever Hospital, there were three nuns, two probationers by day and one night nurse, and one paid wardsmaid and one inmate. There was a six-month fever course in the Cork District Hospital. Dr D Horgan of 11 Sydney Place, Cork was appointed eye specialist.

Note: Forthcoming June Walking Tours with Kieran, all free, 2 hours

• Saturday 17 June, Turners Cross & Ballyphehane Historical Walking Tour, meet at Christ the King Church, Turners Cross, 12noon (finishes a Ballyphehane Park)

• Saturday 24 June, Old Workhouse Tour, meet at entrance to St Finbarr’s Hospital, Douglas Road, in association with the Friends of St Finbarr’s, 12noon

Caption:

899a. Map of Cork Union complex with Cork District Hospital, c.1910 (source: Cork City Library)

McCarthy: Public Consultation Workshops on Future of Docklands Crucial

Cllr Kieran McCarthy has welcomed ongoing developments in the Docklands quarter of the city from Blackrock through Pairc Uí Chaoimh, the Marina Park to Centre Park Road. “it is clear there in a progressive energy in this corner of the city at this present moment; in continuing progress and to meet the current economic climate and the demand for housing, a new Cork City Docks Local Area Plan will replace the South Docks Local Area Plan 2008 and the expired North Docks Local Area Plan 2005. The Tivoli Docks LAP will be a new plan. All of these area have seen lands been incorporated into NAMA and it is very important that their future is unlocked and older plans are amended”.

“As a first step, the City Council is undertaking a pre-plan issues exploration consultation and invites all stakeholders and interested parties to identify the issues that they feel need to be addressed in the proposed LAPs and how the areas should be redeveloped. The Cork City Docks (Local Area Plan) Issues Paper and the Tivoli Docks (Local Area Plan) Issues Paper can be viewed at www.corkcity.ie/localareaplans”.

The public Consultation workshop to promote discussion about the future of the Cork City Docks and Tivoli Docks is being held on Tuesday 20 June 2017 between 6pm-9pm (with light bites between 5pm-6pm) at the Clayton Hotel, Lapp’s Quay, Cork. Workshop places are limited and the City Council asks that interested people RSVP in advance of the meeting by emailing planningpolicy@corkcity.ie or ringing 021– 492-4086 / 021-492-4757. The City Council aims to ensure a good balance in those participating in the event. Cork City Council invites written submissions from you to inform the plan-making processes. The deadline for the receipt of submissions is 1.00pm on Friday 7 July 2017.

Comments by Kieran, Report of the Expert Advisory Group on Local Government Arrangements in Cork, June 2017

Report of the Expert Advisory Group on Local Government Arrangements in Cork

Comments by Cllr Kieran McCarthy, Cork City Council Meeting, June 2017

This is a very welcome document in terms for Cork City’s Council’s perspective on the Local Government Review.

I think it’s a document to note more so than adopt; I have a lot of questions about aspects of the document – and just because we are now getting what we want – we shouldn’t just take the first cheque that comes our way – winning a battle – doesn’t mean we have won the overall war.

I certainly agree with the thoughts that an implementation team should be moved straight away to work through the many questions within this document and address any clarifications needed.

There is a scarily short lead into the next local elections of 2019.

The sooner the implementation oversight body test the proposals within this document the better in an effort to forge forward.

This document needs to be plugged into the submissions of the City and County Councils for the NPF around planning for the next thirty years.

And there are a lot more questions to ask:

If we are agreeing with the proposal for a five-year term for a Lord Mayor – then we should go all the way and propose a directly elected Lord Mayor by the public – a Council elected Lord Mayor runs the risk of one political party ruling the roost for five years.

This document is very light on financial figures, which raises questions for me similar to the County Council’s, and I note their queries that they are not against the document, which is a positive development but are seeking clarifications, all of which I agree with and also such questions need to be asked by our side in order to get a successful outcome for us.

I have questions around costs of transfer of directorates, staff and assets – I would like to get clarification figures on the costings around social housing, roads and environment in the proposed new areas for the city.

I would like the oversight body to provide us with the costs behind the transfer of outstanding debts including commercial rates.

I agree with the point that there has to be long term financial sustainability of the reconfigured County Council – but I note most of all the proposal of providing the County Council with 40 million euros a year for ten years – near half a billion euros over a decade – a lifeline to keep the County Council alive – that’s a huge debt to hang over any city authority – we need to send out a strong signal that such a debt is not sustainable over 10 years.

Again all of this debate comes down to the Department of Local Government’s financing of local authorities.

The emerging city area must have proper funding to encompass another 100,000 people – there is nothing within this document about what extra income will come to the new city council – if the extra income is for example e.40m per annum– it wouldn’t be financially sustainable to take on any new debts – and try to develop the region at the same time and look after the everyday requirements.

We need proper finance figures. I can support many of the report’s recommendations but do not endorse all of it. I have many finance questions, I need answered by the implementation oversight body.

Cllr McCarthy: Crowd Control or Missed Opportunity

Arising from the review of limiting tourists numbers at the English Market, Independent Cllr Kieran McCarthy has acknowledged the lesser numbers freeing up trade in the English Market but again makes the point of the opportunity to tell the story of Gastronomy in Cork City and Region; “there is a clear interest in the history of the market and in the food itself; there is a huge opportunity for the region to promote these stories. The English Market is a thriving food venue but some other venue should be developed close by to tell the story of the market viz-a-vis a small food museum and an opportunity to buy English Market hampers of food. The English Market INC can be more than just a market. There is an opportunity to push more of an international story. We can do more to push and showcase Failte Ireland’s food trails of Cork”.

“There are international gastronomy trails in several countries across the world and even college courses in colleges such as CIT which aim to reveal people and key influences in the historical development of regional gastronomy, and the evolution and social, cultural and economic influences of contemporary Irish cuisine and Irish culinary arts”.

“Apart from the physical market, we should also be championing its heritage and legacy in our city and region more in the form of a food centre or on a digital hub; at the moment in time, this is a missed opportunity”.

Report, Expert Advisory Group on the future of local government, 9 June 2017

Report:

https://www.housing.gov.ie/sites/default/files/publications/files/report_of_the_expert_advisory_group_on_local_government_arrangements_in_cork_21-04-17.pdf

Cork City Council has welcomed the publication today by Minister for Housing, Planning, Community and Local Government, Simon Coveney of the report by the Expert Advisory Group on the future of local government in Cork city and county.

Cork City Council Chief Executive, Ann Doherty said: “We welcome the publication of the report by Minister Simon Coveney. With our Elected Members, we shall study its contents in detail and evaluate its implications for Cork city as the economic driver of the region and for its strategic role as an effective and sustainable counterbalance to the Dublin region”.

Under the chairmanship of Jim MacKinnon, the Cork Local Government Arrangements Report was tasked with undertaking a thorough analysis of the issues dealt with in the Cork Local Government Review Committee in September 2015. It was also to examine the potential of local government in furthering the economic and social well being and sustainable development of Cork city and county.

Its terms of reference included considering the strategic role of Cork city as a regional growth centre, an evaluation of governance necessary to safeguard the metropolitan interests of the city, the examination of local government leadership at executive and political levels, the possibility of establishing an office of a directly elected mayor and the possibility of devolving some power from central to local government.

Jim MacKinnon, CBE is a former Chief Planner at the Scottish Government. Former Chairman of An Bord Pleanála and Eirgrid Chair, John O’Connor, former President and board member of the Cork Chamber of Commerce, solicitor, Gillian Keating and Chief Executive of Richmond and Wandsworth Councils, Paul Martin also sat on the expert advisory group.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 8 June 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 8 June 2017

The Wheels of 1917: The Irish Convention

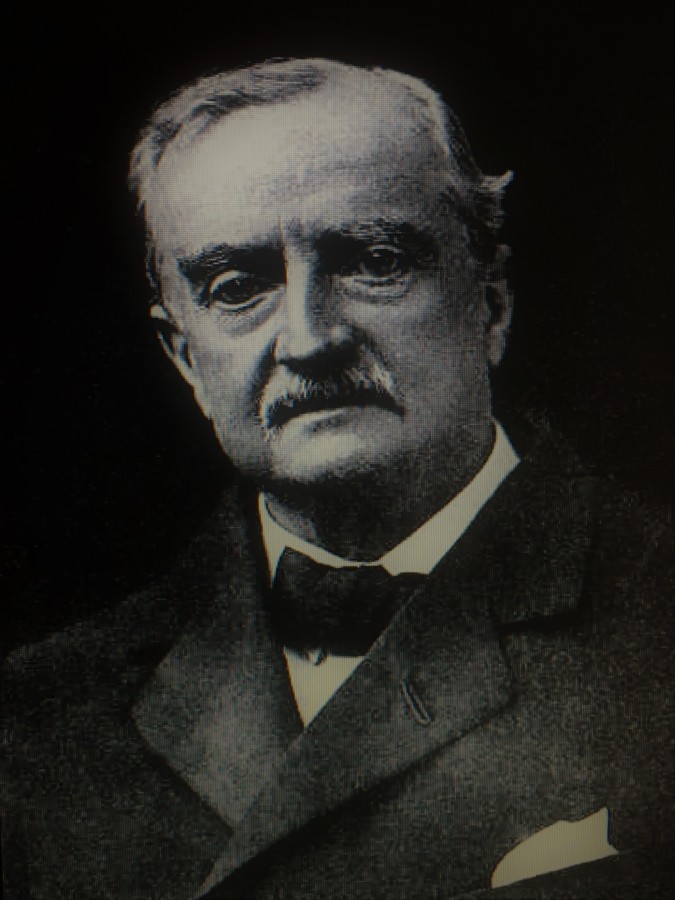

June 1917 coincided with the ground being laid for further national discourse on the future government of Ireland in the form of the Irish Convention. The report of the outcomes of the Convention were compiled and published by Horace Plunkett in 1918.

In a letter dated 16 May 1917 and addressed to Mr John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, the Prime Minister Lloyd George expressed his hope that “Irishmen of all creeds and parties might meet together in a Convention for the purpose of drafting a constitution for their country which should secure a just balance of all the opposing interests”. Invitations were extended to the Chairmen of the thirty-three County Councils, the Lord Mayors or Mayors of the six County Boroughs. The Chairmen of the Urban Councils throughout Ireland were requested to appoint eight representatives, two from each province. The Irish Parliamentary Party, the Ulster Parliamentary Party and the Irish Unionist Alliance were each invited to nominate five representatives.

An invitation was extended to the Roman Catholic Hierarchy to appoint four representatives; the Archbishop of Armagh and the Archbishop of Dublin were appointed to represent the Church of Ireland, and the Moderator of the General Assembly to represent the Presbyterian Church in Ireland. Invitations were also extended to the Chairmen of ‘the Chambers of Commerce of Dublin, Belfast and Cork, and to labour organisations, and the representative peers of Ireland were invited to select two of their number. All these invitations were accepted except by one Chairman of a County Council. Invitations intended to secure representation of the Sinn Féin party and the All for Ireland party were declined, as were the invitations extended to the Trades Councils of Dublin and Cork.

On Thursday evening, 14 June 1917 an inaugural public meeting to discuss the Irish Convention was held in Cork City Hall. The proceedings were published by the Cork Examiner a day later. The meeting comprised merchants, traders, members of the various professions and other citizens of Cork and met to pass a resolution in connection with the future government of Ireland. It was one of the largest and most representative meetings that had assembled in the City for many years, the attendance numbering between 500 and 600, many of whom held very divergent views on the Irish Home Rule situation. Complementary to that at the back of the hall were a section of young men representing Sinn Féin numbering between 40 to 50.

The Chairman Bertram Windle explained that he occupied the chair because the Lord Mayor, T C Butterfield, whom they would naturally expect to find in the chair, considered that he was too closely identified with “party politics” to do so. Windle wished to say distinctly what the meeting was and what it was not; “it was a meeting of the citizens of Cork desirous of promoting the success of the forthcoming Convention”. At this point, one of the young members of Sinn Féin stood up and shouted: “Is the resolution passed last Tuesday night by the Sinn Féin organisation in Cork going to be read here?”. The chairman answered in the negative, and the interruptions from the back of the hall continued. Alderman Beamish rose to a point of order, and asked that all in favour of the object of the meeting stand up. In response every man in the Hall, with the exception of the Sinn Féin representation, rose to their feet.

Mr A F Sharman Crawford, took to the floor, and noted that he felt it a great privilege to propose the resolution, which was the object of the meeting. The resolution was ”That we, merchants, traders, members of the various profession, and other citizens of Cork, in meeting assembled), do hereby cordially welcome the holding of a Convention, to be comprised of Irishmen of all creeds, classes, and politics to consider the most satisfactory scheme for the future Government of Ireland, and we earnestly hope that all the members of such a Convention will enter upon their deliberations with an open mind, and in a broad and liberal spirit fully determined to arrive at some agreement which will tend to the future welfare and prosperity of our common country”.

Mr T B Lillis, of the Munster and Leinster Bank, said he desired to offer a few brief words in support of the resolution. He highlighted that it was not a meeting of politicians, but of business men who were fully representative of the commercial, trading, professional and financial interests of the capital city of Munster. He deemed that “they had the assured conviction, derived from sources of special knowledge which were open to them, that the economic condition of Ireland was never so sound and prosperous as it was at the moment, and their great industry of the land was prospering exceedingly. The prospect of the successful development of our country was never so promising”. At this stage, a young fellow advanced on to the platform and handed the Chairman a Sinn Féin leaflet. Ignoring the intervention, continuing Mr Lillis said they knew that as a result of the “strife and unrest and dissention which were allowed to prevail that the progress of the country was stilted”. The motion was later approved. The Irish Convention held one of its meetings in Cork on 25 September 1917.

Note: June Walking Tours with Kieran, all free, 2 hours

-

Tuesday 13 June, Ballinlough Historical Walking Tour, meet at Beaumont BNS at Beaumont Park, 6.45pm (finishes Ballinlough Road)

-

Wednesday 14 June, Douglas Historical Walking Tour, meet at St Columba’s Church Carpark, 6.45pm (finishes at the Church again)

-

Saturday 17 June, Turners Cross & Ballyphehane Historical Walking Tour, meet at Christ the King Church, Turners Cross, 12noon (finishes a Ballyphehane Park)

-

Saturday 24 June, Old Workhouse Tour, meet at entrance to St Finbarr’s Hospital, Douglas Road, in association with the Friends of St Finbarr’s, 12noon

Caption:

898a. Mr John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, who headed up the roll out of the Irish Convention in the summer of 1917 (source: Cork City Library)

McCarthy: Book Twenty Explores Secret Cork

Cllr Kieran McCarthy’s 20th book has hit Cork bookshelves and it entitled Secret Cork. Published by Amberley Press, the new publication is a companion volume to Kieran’s Cork City History Tour (2016) and contains sites that Kieran has not had a chance to research and write about in any great detail over the years. Secret Cork takes the viewer on a walking trail of over fifty sites. It starts in the flood plains of the Lee Fields looking at green fields, which once hosted an industrial and agricultural fair, a series of Grand Prix’s, and open-air baths. It then rambles to hidden holy wells, the city’s sculpture park through the lens of Cork’s revolutionary period, onwards to hidden graveyards, dusty library corridors, gazing under old canal culverts, across historic bridges to railway tunnels. Secret Cork is all about showcasing these sites and revealing the city’s lesser-known past and atmospheric urban character.

Cllr McCarthy notes; “Cork’s story is really enjoyable to research and promote. I still seek to figure out what makes the character of Cork tick. I still read between the lines of historic documents and archives. I get excited by a nugget of information that completes a historical puzzle I might have started years ago. I still look up at the architectural fabric of the city to seek new discoveries, hidden treasures and new secrets. I am still no wiser in teasing out all of Cork’s biggest secrets. But I would like to pitch that its biggest secret is itself, a charming urban landscape, whose greatest secrets have not been told and fully explored”

Continuing Cllr McCarthy highlighted that we all become blind to our home place and its stories; “we walk streets, which become routine spaces – spaces, which we take for granted – but all have been crafted, assembled and storified by past residents. It is only when we stand still and look around that we can hear the voices of the past and its secrets being told”.

“Cork’s story has been carved over many centuries and all those legacies can be found in its narrow streets and laneways and in its built environment. The legacy echoes from being an old ancient port city where Scandinavian Vikings plied the waters 1,000 years ago – their timber boats beaching on a series of marshy islands – and the wood from the same boats forming the first foundations of houses and defences”.

“Themes of survival, living on the edge, ambition, innovation, branding and internationalisation are etched across the narratives of much of Cork’s built heritage and are among my favourite topics to research. Indeed, I fully believe that these are key narratives that Cork needs to break the silence on more and this is a book constructed on those themes”.

Secret Cork is available in Cork bookshops or online at Amberley Press.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 1 June 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 1 June 2017

The Wheels of 1917: The Age of Public Houses

One hundred years ago this month, meetings were held in Cork City to showcase the rationing of beer and stout. The Beer Restrictions Act cut down the manufacture of such products to one-third of the output. A letter to the editor of the Cork Examiner on 2 June 1917 by a representative of the retail traders Mr Michael O’Mullane explains the effects of rationing. Accordiing to Mr Mullane the curtailment had turned to a drastic situation as the one-third was not fairly or evenly divided on a pro rata basis after the product has left the hands of manufacturers.

Hundreds of licensed traders were complaining that they were not getting anything like the one-third of their normal supply. In almost every town in the country there was a brewer agent, or rather purchasing agent. These purchasing agents were, in nearly all cases, retail vintners themselves, and they appeared to be withholding from their former retail customers the greater part of the one-third supply. The purchasing agents claimed they could distribute barrels of stout as they like, i.e. that they could give two or three-thirds to one customer, and one-sixth, one-twelfth, or none at all to another customer. According to Mr O’Mullane, although the liquor traffic was not State controlled it could be argued to be so virtually, owing to the operations of the Beer Restrictions Act as applied to the manufacturers.

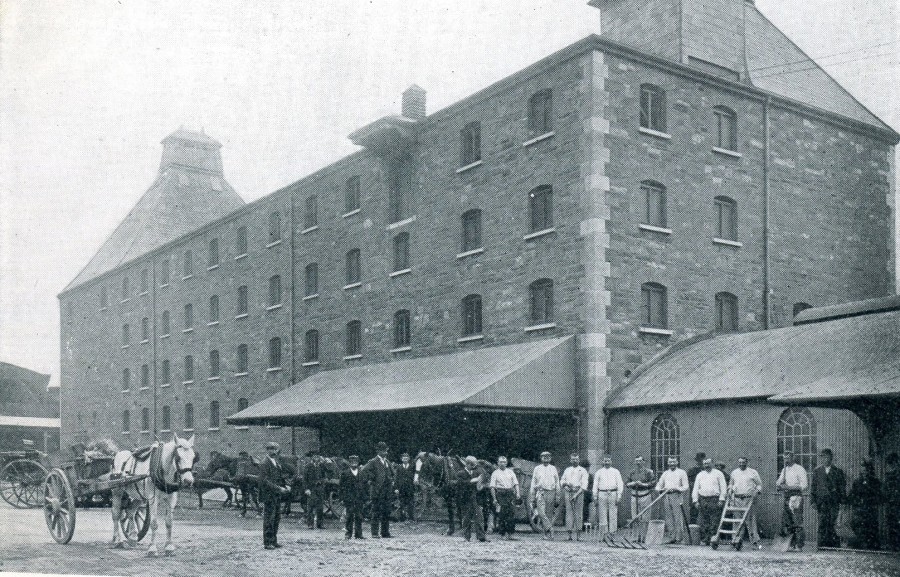

For the purpose of protesting against the rationing and intentions of the Westminster Government with regard to the Irish brewing and distilling industries, a public meeting was held in Cork City Hall on Friday evening, 1 June 1917. Lord Mayor Thomas C Butterfield presided. The attendance was large drawing interested parties from the city and county. The proceedings were published on 4 June in the Cork Examiner. The Lord Mayor noted that the numbers affected by the rationing were impossible to calculate; “One could enumerate indefinitely the number of people who would be affected by those restrictions, such as the brewers, the brewery workers, the vintners and the assistants. As far as the workers were concerned, it was elementary knowledge that the men employed in breweries and distilleries or maltings were men who had spent most of their lives at their respective businesses, and if they were disemployed, they would be absolutely no use for anything else”.

The Lord Mayor outlined that vintners, for the most part, lived by the sale of liquor. Many of them had large families, and that it would be a crime if their means of livelihood was taken from them. The taxpayer, too, would be hard hit; “the revenue from the sale of liquor would be reduced, and this, deficit would have to be made up some way”. The farmers, too, would not have a market for their produce. “It the Government were determined to crush out the distilling and brewing trade in Ireland, they had a right to compensate the people for it”.

The City High Sheriff William O’Connor moved a resolution “calling on the Government to relax, or at least to modify, the restrictions at present in force with regard to the Irish brewing and distilling industries which were causing so much inconvenience, hardship and dissatisfaction to the general public, pointing out that such drastic curtailment, as far as Ireland was concerned, was not absolutely necessary”. Despite revealing himself as a teetotaler, he highlighted that what he wished to speak about at the meeting was “the injustice sought to be perpetrated on Ireland by the Government”. The City Sheriff noted that outside the shipbuilding industry in Belfast, British rule had left Ireland practically no other industry of any importance with the exception of the brewing and distilling industries.

The City Sheriff continued his concerns about the effects on the circa 520 public houses in Cork city, with its population of about 76,000—that was one public-house for every 150 persons. The Cork breweries employed around 500 men, and he had been informed that as consequence of the regulations of the Government one brewery discharged 70 men and at another brewery 30 men. He questioned the future employment prospects of those made redundant; “What was to become of these men – that was a point that deserved their most serious consideration. The licensed vintner?, the vast majority of whom were respectable men and women, had always contributed in a most generous manner to all charitable objects as well as to every movement for the betterment of the people and the country, and were those traders, after putting all their savings into their promises, to be thrown on the roadside?”. To him, the licensed vintners circulated a large amount of money and gave a good deal of employment, and he held that if they were to be treated in such a manner they should be given adequate and reasonable compensation.

Cllr Timothy Sheehy said they should demand of their members of Parliament to “strike a decisive blow in their cause”. He argued that for a century England had starved the industries of Ireland, and they were now going to continue that policy. He believed the meeting would have a great effect on the vital question of whether they were going “to allow Lloyd George and the Government crush out those great industries”. After several more passionate speeches, the motion was unanimously passed.

Captions:

897a. Murphy’s Brewery, Blackpool, 1903 (source: Cork City Library)

897b. Malt house and yard, Murphy’s Brewery, Blackpool, 1903 (source: Cork City Library)