Category Archives: Cork History

McCarthy’s Upcoming Blackrock Historical Walking Tour

Cllr Kieran McCarthy will lead a historical walking tour of Blackrock Village on Saturday 30 September, 12noon (starts at Blackrock Castle, two hours, free). Cllr McCarthy notes: “A stroll in Blackrock is popular by many people, local and Cork people. The area is particularly characterised by beautiful architecture, historic landscapes and imposing late Georgian and early twentieth century country cottages to the impressive St Michael’s Church; every structure points to a key era in Cork’s development. Blackrock is also lucky that many of its former residents have left archives, census records, diaries, old maps and insights into how the area developed, giving an insight into ways of life, ideas and ambitions in the past, some of which can help us in the present day in understanding Blackrock’s identity going forward”. More on Kieran’s heritage work is on www.corkheritage.ie

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 21 September 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 21 September 2017

The Wheels of 1917: Arthur Griffith in Cork

One hundred ago this week the leaders of the National Sinn Fein movement, Count George Noble Plunkett (father of Joseph Plunkett), Eoin McNeil and Arthur Griffith came to Cork as part of a series of Sinn Fein re-organisation rallies in the country’s principal towns and cities. On Sunday 24 September 1917, on the Grand Parade, three meetings were addressed by them and proceedings were described in the Cork Examiner. Countess Markievicz had spoken in Cork some weeks previously on 11 August 1917 (see previous articles).

The principal platform was erected opposite the offices of the Cork Sinn Fein Executive (56, Grand Parade); there were two other platforms on waggonettes to the right of the National Monument and to the left of the Berwick Fountain respectively. The crowd present numbered several thousand. During the morning contingents arrived by cycle and car from distant parts. The Sinn Fein colours were very present and on the banners there were expressions in Irish of welcome and support.

Contingents representing Cork City Volunteers, City Wards, Sinn Fein Clubs, Girls’ Volunteer Clubs, together with the following bands; Butter Exchange, Blackrock, and Cork Volunteers were present. Contingents of Volunteers also attended from Whitechurch, Mourneabbey, Ballingeary, Dooniskey, Carriganimma, Kilnamartyra, Mallow, Kanturk, Dungourney, Watergrasshill, Castletownroche, Millstreet, Clogheen, Aghadilane, Douglas, Blackrock, Ballinhassig, Ballinadee, Dunmanway, Skibbereen, Bantry, Ballinagree, Ballyvourney and Clondrohid.

On the principal platform Liam de Roiste, vice-chairman of Sinn Fein in Cork, presided, and having addressed the meeting in Irish, introduced Arthur Griffith. Arthur was moved by the valour of the Rising participants and wanted to join them but was asked by the leaders not to as it was felt his propaganda skills in the future would be of greater value. After the 1916 Rising he was arrested and imprisoned but he was released at the end of the year.

Arthur Griffith recalled that his first address to the people of Cork was seventeen or eighteen years previously. He had come with others to organise public rallies to oppose the Westminster Government in seeking recruits for the army, then engaged in fighting the Boer War. He resented the ongoing suggestion made in a variety of press statements that the only safeguard between Ireland and conscription was the presence of an Irish Party in Parliament. He claimed that John Redmond MP, representing Ireland’s interest in Westminster had argued that if Parliament showed him there was any necessity in this country for imposing conscription he would support it. Countering John Redmond, Arthur Griffith argued that Sinn Fein wished for the people to organise and back up the claim of an Independent Ireland to be put before the World War Peace Conference.

Arthur Griffith refused to join the ongoing Irish Convention, which was meeting to debate Irish self-government. He deemed that three of its conditions it set out should not be conceded. He called firstly that delegates should be elected by the vote of the people of Ireland; secondly that whatever decision that the majority came to, even the establishment, of an Irish Republic, that that decision should be accepted by Westminster; and thirdly that England would pledge herself to the United States and her Allies in Europe to carry out whatever decision was arrived at. He strongly held that the Convention was not a Convention of the Irish people, but of the Westminster Government’s nominees. The Sinn Fein policy is to make Ireland completely independent. They deny all authority or right of England to legislate for Ireland. They were going to the Peace Conference to enforce that demand did not recognise English authority by sending representatives to the Westminister Parliament.

Arthur Griffith outlined that Sinn Fein proposed to set up a Constituent Assembly representative of the Irish people who were prepared to assemble in the capital of Ireland. He compared Ireland’s case to Hungarian Deputies refusing to recognise the authority of Austria 60 years previously. In the proposed Irish Assembly they would formulate measures for the nation, “to guide and lead the nation in the struggle for their independence, and to set before the Peace Conference their claim for the restoration of Ireland’s national independence”. Arthur outlined; “Ireland should come before the Peace Conference because America was primarily in the war to establish the freedom of the seas. That question would never be solved until the situation of Ireland in Europe is settled. Ireland was the key to the freedom of the seas, became it controlled the Atlantic”.

Concluding at his platform, Arthur Griffith referred to the upcoming visit of the Irish Convention to Cork (see next week’s column) in the days following his speech, and asked that the Cork people not support it or protest against it. He noted: “Simply let it go by. It may come to a conclusion, or it may not; but with anything that did not give back Ireland its complete independence Sinn Fein would have nothing to do with it; the Convention suggests some form of Government inside the British Empire”. Arthur envisaged that there would be peace in the ensuing months, and predicted that before the summer of 1918 the World War Peace Conference should have met and the future of Ireland will then have been decided.

Looking to read more Our City, Our Town articles from over the years, log onto the index at my website www.corkheritage.ie

Secret Cork (2017) by Kieran McCarthy is now available in Cork bookshops or online at Amberley-books.com

Captions:

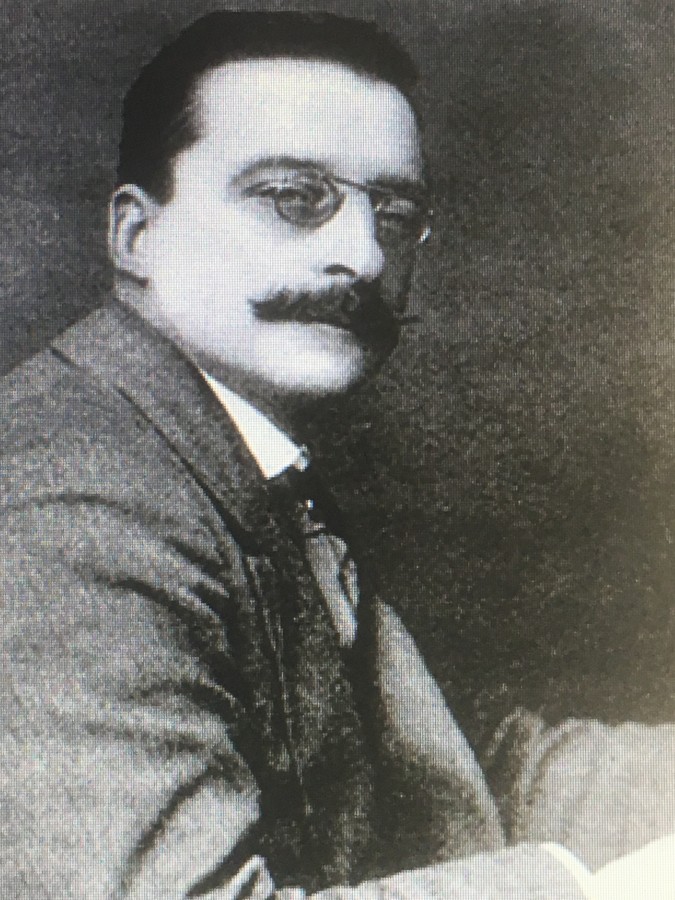

913a. Arthur Griffith (source: Cork City Library)

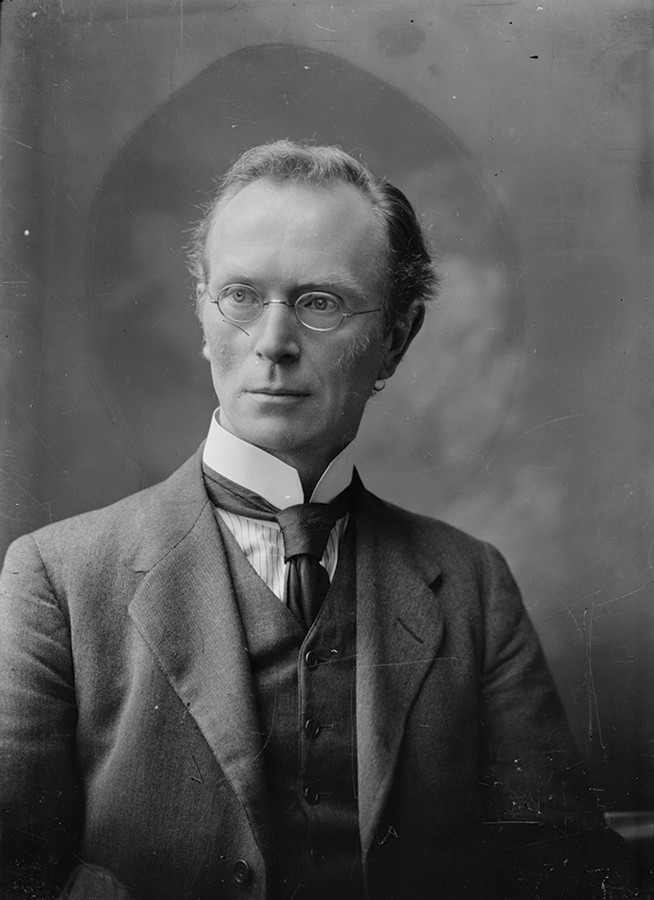

913b. Eoin McNeil (source: Cork City Library)

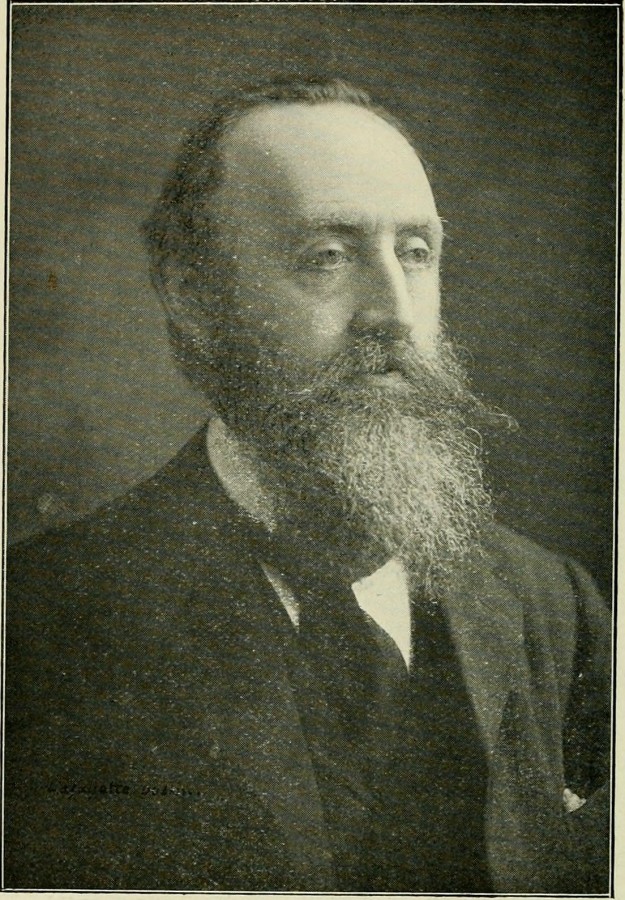

913c. Count Noble George Plunkett (source: Cork City Library)

UNESCO Conference – Cork Learning City 2017

Cork has been successful in its bid to host the third UNESCO Global Network of Learning Cities Conference in Sept. 2017. The two previous conferences were held in Beijing 2013 and Mexico 2015, each involved over 600 delegates from countries worldwide. The conference will be presented by UNESCO Institute of Lifelong Learning, held in Cork City Hall, from Sept 18th -20th 2017, supported by Cork City Council and Cork ETB hosted with its Learning City Project partners, UCC, CIT, and other agencies in the city.

Sept 20th Learning Festival Showcase Programme

This is a first for Ireland and for Europe:

Cork is the only Irish city currently recognized by UNESCO for its excellence in the field of Learning, and was one of just 12 cities globally, and 3 in Europe, presented with inaugural UNESCO Learning City Awards in 2015. A case study of the city was published by UNESCO Institute of Lifelong Learning (UIL) in Unlocking the Potential of Urban Communities, Case Studies of Twelve Learning Cities also in 2015. The other two European cities are Espoo (Finland) and Swansea.

Cork successfully bid against 3 other European cities to host the conference because of its track record. The international conference presents Ireland with a unique opportunity to further cement the reputation of the country and the city as a centre of excellence in education and learning. The UIL Directorate team visited Cork during the Lifelong Learning Festivals of 2015 and 2016 and selected the city following a strong bid prepared with the assistance of the Cork Convention Bureau who have recognised experience of hosting international conferences of this scale in the city previously.

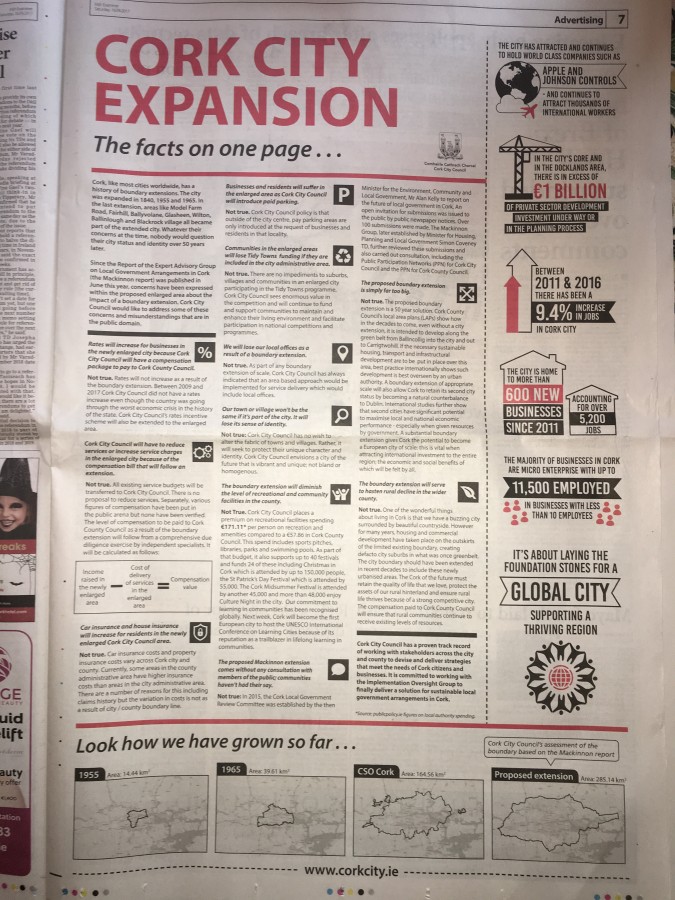

Myth Busting, Cork City Council & Cork City Expansion

Advertisement in Irish Examiner, taken out by Cork City Council, 16 September 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 14 September 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 14 September 2017

The Wheels of 1917: American Sailors on Cork Streets

In early September 1917, a coast to coast call for military men was made across the United States of America. The calls strove for a quarter of a million men to enlist in the American forces on battle fronts in Western Europe. They were asked to gather at the mobilisation camps. In the first week of September up to 30,000 men were paraded in New York. They were drawn from 26 States and the district of Columbia. This division, which was sent off to France, represented more than half of the states of the United States.

Over the two years between 1917-1919, thousands of US naval personnel would be stationed in Cork Harbour and Bantry Bay, engaging in the war against German U-boats and seeking to ensure convoy security. In September 1917 in Queenstown (now Cobh) according to the diary of American Naval Commander Joseph Knefler Taussig, there were eight American destroyers – Wadsworth, Porter, Shaw, Ericsson, Jacob Jones, Paulding, Burrows, and Sterett – all helping to convoy merchant ships in the Irish sea. Their wide web of facilities in the county by war”s end comprised sites in Cobh, Passage West, Haulbowline (now the Irish Naval Service headquarters), Ringaskiddy, Aghada, Bere Island, Berehaven and Whiddy Island. Aside from their storage and barrack sites, the Americans also set up training areas, recreational centres and a hospital.

The hundreds of sailors involved in these ships were quite the celebrity in the harbour and in the city. In July 1917, the officers of the Cork County Cricket Club wrote to the US embassy in London offering their pavilion and grounds at the Mardyke to the Americans should they need them. The very offer led the commanders of two of the Cobh-based vessels, the USS Melville and the USS Trippe, to think about staging a baseball match between their respective crews. it was decided to use it to raise funds to support the local Queenstown War Workers fund. It was played on a midweek July afternoon before a crowd of 3,000 people. There were many American sailors among them, but the majority were local onlookers.

In addition, some newspaper reports (Cork Examiner & Evening Echo) noted that hundreds of young women each night were drawn to Queenstown to mix with those sailors on shore leave. That was enough to raise the tempers of some sidelined local men. In the city on Monday 3 September 1917 a party comprised of young boys hissed and jeered at American sailors whom they chanced to meet. It started in King street (now MacCurtain Street). American sailors accompanied by young girls attracted the attention of a number of young fellows, who immediately vented their resentment by jeering. They followed the sailors and girls until quite a large crowd gathered and the girls and sailors parted. They passed another number of Americans, and the crowd directed their efforts against these. The crowd followed and jeered at them to the Lower Glanmire Road Railway Bridge. Here the police intervened, and moved the crowd back towards King Street. Near the Coliseum an American sailor, standing in the portico of the theatre, was the centre of attention. It transpired he was attacked by a group of youngsters.

The police continued to move the crowd along King Street, down Bridge street, and on to Patrick’s Bridge. By the time the activity had dwindled somewhat and matters were quieter. But a group of juveniles, bearing a Sinn Fein flag in front, crossed over the bridge in the direction of Bridge Street, where the police were in force. They had not gone, far when the police, with batons in hand, charged them. The party ran down Pope’s Quay, and some stones were thrown, amidst shouts of “Up Dublin” and “Up the Huns”.

Following the city incident, the American sailors were forbidden to come into Cork City. With restricted shore leave in Queenstown there was a number of disturbances there involving American sailors and local civilians. The civilians displayed ill-feeling towards women from Cork City who had been travelling to Queenstown each night to meet the sailors. Police in Queenstown reported several incidents of disorder, but these mostly arose from the Americans arguing among themselves whilst on shore leave. Lively behaviour and a few isolated “scraps” were reported, but there were no assaults or damage to property. Local police confirmed that the glass door of a public house on King Street was broken by a party of American sailors. It is not known if the incident occurred owing to an accident or resentment on being refused drink after authorised hours.

Tensions were heightened on Saturday 8 September 1917 when a Cork labourer was killed during disturbances involving an American sailor at Queenstown. The Haulbowline man, Fred Plummer, was struck by the sailor with a closed fist, his head hitting the concrete flagged footpath of the beach. Plummer was unconscious when taken to Queenstown General Hospital, where he subsequently died from what an inquest found to have been a fracture of the skull.

To highlight the social history of the American Navy in Cobh in 1917, an exhibition has been researched and prepared by archaeologist and historian Damian Shiels. It is designed and produced in association with Sirius Arts Centre, Cobh and is on display till 17 September. It is entitled Portraits: Women of Cork and the U S Navy 1917-1919 and explores the marriage of some American sailors and Cork women. There is also some great information on this era on display in Cobh Museum.

Captions:

912a. American Sailors at Queenstown now Cobh in 1917 (source: Cobh Museum)

912b. U S Sailors patrolling streets of Queenstown (source: Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington)

European Opportunity for Elizabeth Fort

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 31 August 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 31 August 2017

The Wheels of 1917: A Fire at Cork Spinning and Weaving Company

On Friday 24 August 1917, the premises of the Cork Spinning and Weaving Company at Millfield in Blackpool was the scene of an outbreak of a great fire. It resulted in the loss of large and valuable stocks of flax and other manufacturing materials. The fire was first discovered just before noon in the roughing and hackling departments of the spinning mill and by that time it had secured a solid grip on the buildings and spread rapidly. On the alarm being raised all the hands employed in the different departments escaped into the adjacent yard spaces. There, they were marshalled away at a safe distance from danger by the heads of the firm. The departments affected ran parallel and were divided by a stout wall over which the flames leaped sending the whole roof toppling in.

When the Cork Fire Brigade arrived, they found several male workers endeavouring to hinder the spread of the fire to the rear of the premises. Within an hour after the outbreak, the spread of the flames had been brought under control. All workers were instructed to return to work and provision made for diverting those hitherto employed in the destroyed departments to other branches of the business. About 1.40 pm, when it seemed that danger had been averted, it was found that sparks from the destroyed departments had ignited some of the material in a small adjoining storehouse at the rear, and what looked to be a devastating position was only overcome when the fire brigade intervened. Had the fire reached the main storehouse close by the major portion of the company’s stock might have been burnt out. The brigade worked under Deputy Superintendent Higgins and the City Engineer, Mr Delany, was present throughout.

The main building, a five storey brick building, was constructed between 1864 and 1866 and was the brainchild of William Shaw. Designed by Belfast architects, Boyd and Platt, it was the first industrial linen yarn-spinning mill outside of Ulster. The Millfield Mill was operated by the Cork Spinning and Weaving Company whose directors chose the site outside the city’s municipal boundary due to the fact, the company would not have to pay rates to Cork Corporation. One of its most famous directors was its acting chairman John Francis Maguire, a Westminster MP for Munster and also founder of the Cork Examiner. During construction, the Belfast designers of the mill made sure that fireproof jack-arched floors were present throughout the building and these were supported by cast iron columns supplied by the King Street Works in Cork. The mill began operating on 15 February 1866 operating with 900 spindles and the following year, the company was employing seventy Belfast linen workers along with 630 local women, girls and boys.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the mill was one of the most important flax spinning mills outside of Ulster. As a symbol of local enterprise, the mill was also operating looms for weaving and by 1920 was employing upwards on 1,000 people. The 27th annual report of the Cork Spinning and Weaving Company (available in Cork City and County Archives) reveal that the trading conditions in 1916 were under great difficulties due to scarcity of raw materials. However, the government had secured supplies of Russian flax to keep the mills going. Prices were described at being at a dangerously high level. By 1917 supplies from Russia had been stopped. Irish flax was controlled by Government and spinners were required to spin yarns suitable. A year later, there had been an increase in working capital required owing to enormous increase in price of materials and costs of production.

By January 1921, between 600 and 700 hands were made temporarily unemployed as a result of the closing of the flax mills of the Company. This action was rendered necessary by the fact that the company had sold very little of their stock within the previous few months, and indeed the whole trade was practically at a standstill.

The year 1924 marked the closure of the Cork Butter market adjacent Shandon and the opening of a knitwear factory on the site by William Dwyer. In the 1930s, Dwyer transferred his factory from Shandon to the Millfield textile factory Blackpool in order to expand his business. Three decades later, the Dwyer factory in the 1960s, the factory was witnessing much success and employed 1,100 people. It also attracted other smaller firms to the complex and was one of the city’s largest employers. The House of Dwyer also operated the Lee Hosiery Factory, Lee Shirt Factory and Lee Clothing Factory.

On 8 October 1945, the solemn blessing of Cork’s new Church, the Church of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin took place. It was a gift of William Dwyer to the North Cathedral Parish.

In the mid-1970s, the Millfield Factory was sold to UK firm, Courtaulds. Subsequently, in the 1980s, the factory employed over 3.500 people and in the early 1990s was taken over by Sunbeam Industries Limited, based in Westport. In 1995, Sunbeam Knitwear closed and the site became home to many local enterprises. The old nineteenth century block was devastated by fire on 25 September 2003.

Kieran’s new book, Secret Cork, is now in Cork bookshops.

Captions:

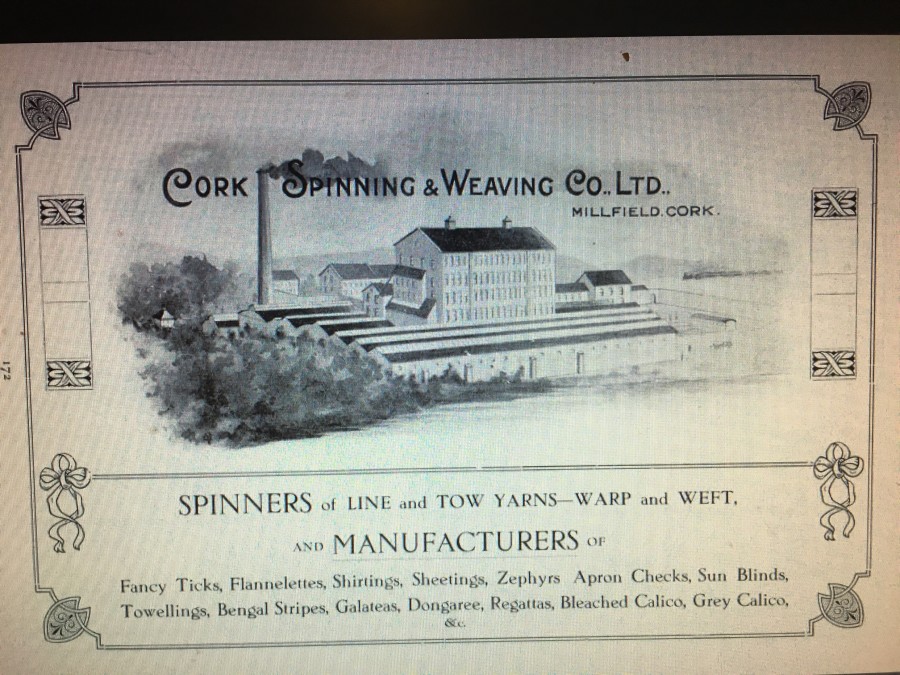

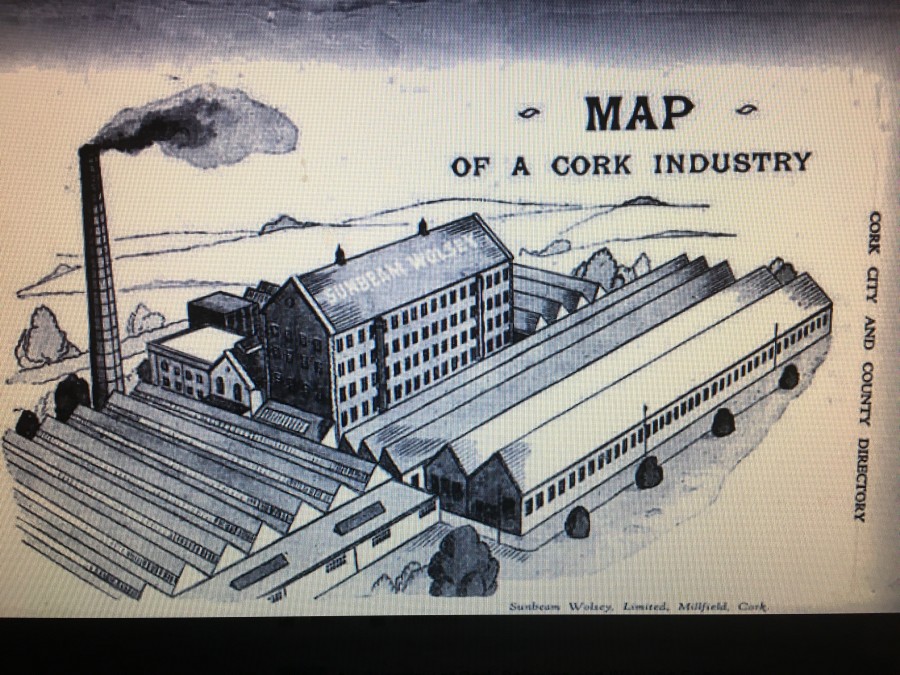

910a. Advertisement for Cork Spinning and Weaving Company, 1917 (source: Cork City Library)

910b. Plan of Cork Spinning and Weaving Company from Guy’s City and County Directory of Cork (source: Cork City Library)

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 24 August 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 24 August 2017

The Wheels of 1917: Countess Markievicz Comes to Cork

Constance Gore-Booth, aka Countess Markievicz, was born on 4 February 1868 in London and was brought up at Lissadell House, County Sligo. She married Polish Count Casimir Dunin Markievicz in 1900. She entered politics in 1907 and in 1909 founded Na Fianna, an organisation for boys, who were taught military drills and the use of arms. During the Easter Rising of 1916 she was second-in-command at St Stephen’s Green. Following the surrender, she was arrested and although initially sentenced to death, this was commuted to life imprisonment. She was released in 1917 and became involved in the ongoing re-organisation of Sinn Fein.

Countess Markievicz arrived in Cork by train on Saturday evening, 11 August 1917 for a Sinn Feiin rally. Large swathes of Sinn Fein members and sympathisers of the movement, foregathered in the vicinity of the railway terminus. With Countess Markievicz travelled Messrs. Herbert Mellows and Joseph Clarke, both members of the Sinn Fein Executive in Dublin. The Cork Examiner of the day highlighted that on arrival they were greeted by the heads of the Sinn Fein movement in Cork consisting amongst others Terence McSwiney and Tomas MacCurtain.

The large procession led by the Pipers’ Band, proceeded along King Street, through the city, and on to the Grand Parade, where a short reception meeting was held. Other sections composing the procession represented ward contingents of the Sinn Fein in organisation, the Boy Scouts, Irish Volunteers Cumann na mBan, whilst in addition to the Brian Boru Pipers’ Band and the Irish Volunteer Pipers’ Band, the Workingmen’s and Butter Exchange Brass Bands also participated.

The public meeting at the National Monument, Grand Parade, was one of the largest kind in Cork for a considerable time. The proceedings connected with the reception were, from start to finish, without incident. The streets were heavily policed and about fifty extra police were drafted in from the county for the occasion.

Tomas MacCurtain, who presided, said it was absolutely unnecessary for him to introduce Countess Markievicz as her name went before her. On behalf of Cork and of Munster he extended to her a very hearty welcome. He noted that such positive support was to show that the “hearts of the citizens of Cork were entirely with the definite aims for which she fought in Easter Week – the putting into operation in this country, instead of the present Government, an Irish Republic”.

Countess Markievicz, who was received with great enthusiasm, addressed the meeting as “Fellow-soldiers and Friends”. She opened by noting that said she was proud to see the brave welcome given her that night because it showed her that Cork City was ready to do as she was pursuing to fight for an Irish Republic. She expressed the view that the welcome given her was not personal, but was a greeting to her as representative of the men who died for Ireland in Easter 1916. She related that the proudest memory of her life was when she worked with them, plotted and planned with them, and her proudest memory of all was that she went, out and planned with them. She compared Easter 1916 to Bunker Hill, which was lost by the Americans in their War of Independence but the national pride amongst the American Continental Army prevailed; “It was that battle gave the idea of nationality to the American nation, and that battle was the first moral victory won by America, and the result was American Independence”. Easter 1916 to Countess Markievicz was the greatest moral victory Ireland ever achieved; she noted that it “welded together the physical forces and the moral forces of the country”. It welded the “policy of Wolfe Tone with that of Parnell”. She highlighted that they were not bloodthirsty rebel or red revolutionists; “They went out in the first battle for an Irish Republic, and to secure that ideal they must show themselves, as their countrymen had done in 1916, ready to die for it”.

Countess Markievicz called on the Cork crowd to rally behind the men who died in Easter Week and that Sinn Fein were re-organising across the country. She wished that Sinn Fein would win every seat for the Westminster Parliament. She spoke about a need for a straightforward Republican policy, a policy for the foundation of an Irish Republic; “we want Irishmen to understand that, and to see that they have a representative candidate put into every position possible. We want them all co organised, to get into the several Republican societies, Sinn Fein Societies, Sinn Fein and Republicanism are the same thing”.

Countess Markievicz wanted the Sinn Fein membership to follow the example of the boys of her Na Fianna organisation to drill and be organised, but also called for “physical force and moral force”; “Their thoughts at the moment of waking should be of an Irish Republic, and their resolution to work the day to help it on. That was what was wanting from every man and woman to be ready to step into the shoes of those now working for them when they had vanished, to be ready to follow in the footsteps of Connolly and Pearse”. She ended her speech with the one message: “Get ready, organise, take the country for themselves”.

Kieran’s new book, Secret Cork, is now in Cork bookshops.

Kieran’s remaining Heritage Week historical walking tours are posted under walking tours at www.kieranmccarthy.ie

Captions:

909a. Portrait of Countess Markievicz, with revolver, in the uniform of Commandant in the Irish Citizen Army, c. 1916 (source: South County Dublin Libraries)

909b. National Monument, Grand Parade, c.1910 (Source: Cork City Through Time by Kieran McCarthy & Dan Breen)

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 17 August 2017

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 17 August 2017

Cork Heritage Open Day, 19 August 2017

Another Cork heritage open day is looming. The 2017 event will take place on Saturday 19 August. For one day only, over 40 buildings open their doors free of charge for this special event. The team behind the Open Day, Cork City Council and building owners, have grouped the buildings into general themes, Steps and Steeples, Customs and Commerce, Medieval to Modern, Saints and Scholars and Life and Learning – one can walk the five trails to discover a number of buildings within these general themes. These themes remind the participant to remember how the city spreads from the marsh to the undulating hills surrounding it, how layered and storied the city’s past is, how the city has been blessed to have many scholars contributing to its development in a variety of ways and how the way of life in Cork is intertwined with a strong sense of place and ambition. For a small city, it packs a punch in its approaches to national and international interests.

The Saints and Scholars route lies to the South side of the city and takes in the birth place of Frank O’Connor and the burial place of Nano Nagle and panoramic views from Elizabeth Fort. The route encompasses places of learning and places of worship finishing up at South Gate Bridge with fabulous views of the magnificent St Fin Barre’s Cathedral.

One of Cork’s most distinctive landmarks, St. Fin Barre’s Cathedral is located where Cork’s Patron Saint founded his first Church and School. It is the diocesan cathedral of the Church of Ireland and the Bishop’s residence is directly opposite the cathedral gate. St Fin Barre’s was designed by the notable architect, William Burges, who also designed the stained glass, the sculptures, the mosaics, the furniture and metal work for the interior. The foundation stone was laid in 1865 and the building was consecrated in 1870. The Cathedral is stylistically late thirteenth century pointed Gothic and is cruciform in shape. It has triple spires with portals to the west front and an abundance of external stone carved detail.

The Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) Meeting House on Summerhill South was designed by WH Hill and was purpose built in 1938 following a move from the old Meeting House in Grattan Street, which dates back to 1677. It is a simple, unadorned meeting room that is used for Quaker worship, as well as a number of community activities. The burial ground lies to the rear of the building. The plain and nearly identical grave stones are a symbol of the Quaker belief in the intrinsic equality of all. These simple headstones are representative of the form and design of Quaker grave markers and were clearly executed by skilled craftsmen.

The wonderful complex of buildings at Nano Nagle Place form a rich architectural assemblage. The triangular wedge of land upon which it sits appears in early maps of Cork. It is not clear when it came into the possession of the Nagle family. The family passed the land to Nano Nagle and when she in turn passed it to her community, the function and shape of the site were set to prevail. The oldest remaining building is the convent that Nano Nagle built for the Ursuline Sisters in 1771. Recent research has shown that many original design details remain, perhaps specified by Nano herself. The Ursuline sisters thrived here and built extensions to that original building in 1775, 1779, and 1790. When the Ursulines moved to Blackrock in 1825 the buildings passed to the Presentation Sisters.

Elizabeth Fort was first built in 1601 by Sir George Carew, the then president of Munster during the reign of Queen Elizabeth 1. The fort was built on a rocky outcrop overlooking the city from the south. Following the death of Elizabeth in 1603, the fort was attacked by the citizens of Cork, however, when the city was re-taken, they were compelled to rebuild it at their own expense. It was replaced in 1624 by a stronger, stone fort, much of which survives today. It is reputed that improvements were also made by order of Oliver Cromwell in 1649.

Backwater Artists Group, Cork Printmakers and CIT Wandesford Quay Gallery are located on Wandesford Quay. This three-bay, four-storey warehouse was originally built circa 1840. Its first use was as a grain store, probably for the nearby distillery. It was then used as a timber yard and went on to become Coleman’s Printers. Backwater Artists Group is one of the largest artist-led studio groups in Ireland, with 29 studios and over 40 artists working from the complex. They are open to the public for Cork Heritage Day, Cork Culture Night and for guided tours, artists’ talks and exhibitions during their annual Open Studio Event, in November. There will be an exhibition of members work on view in our exhibition space.

See www.corkheritageopenday.ie for more information on the city’s great heritage open day and then followed by Heritage Week (information at www.heritage week.ie). My tours are posted at www.kieranmccarthy.ie under the walking tours section or follow my facebook page, Cork Our City, Our Town.

Captions:

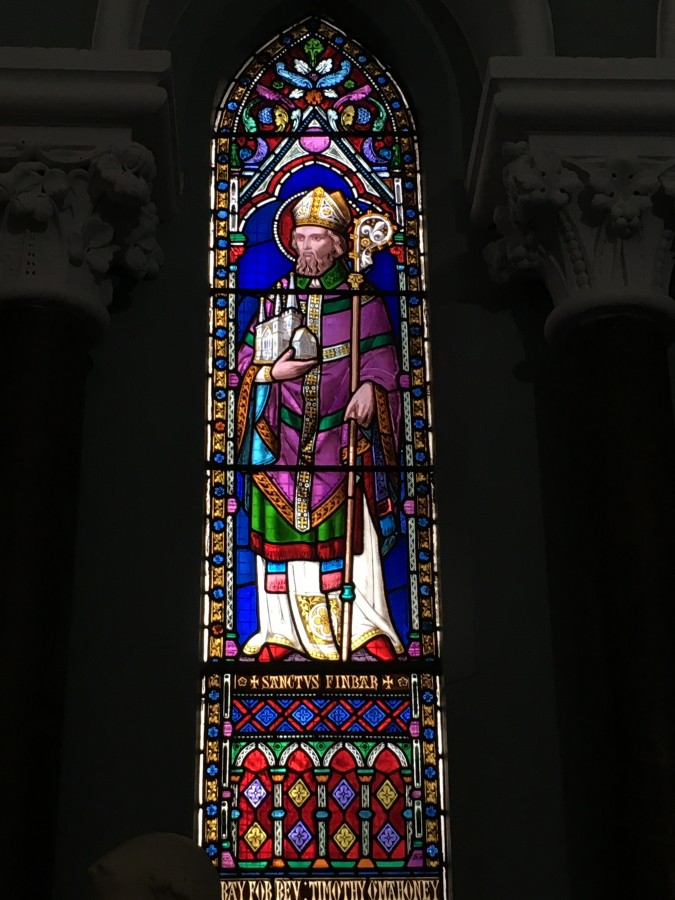

908a. Stained glass window of St Finbarr, Chapel of Presentation Convent, Douglas Street (picture: Kieran McCarthy)

908b. Recent Medieval Open Day, Elizabeth Fort (picture: Kieran McCarthy)