Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 3 October 2024

Making an Irish Free State City – The Future of the School of Commerce

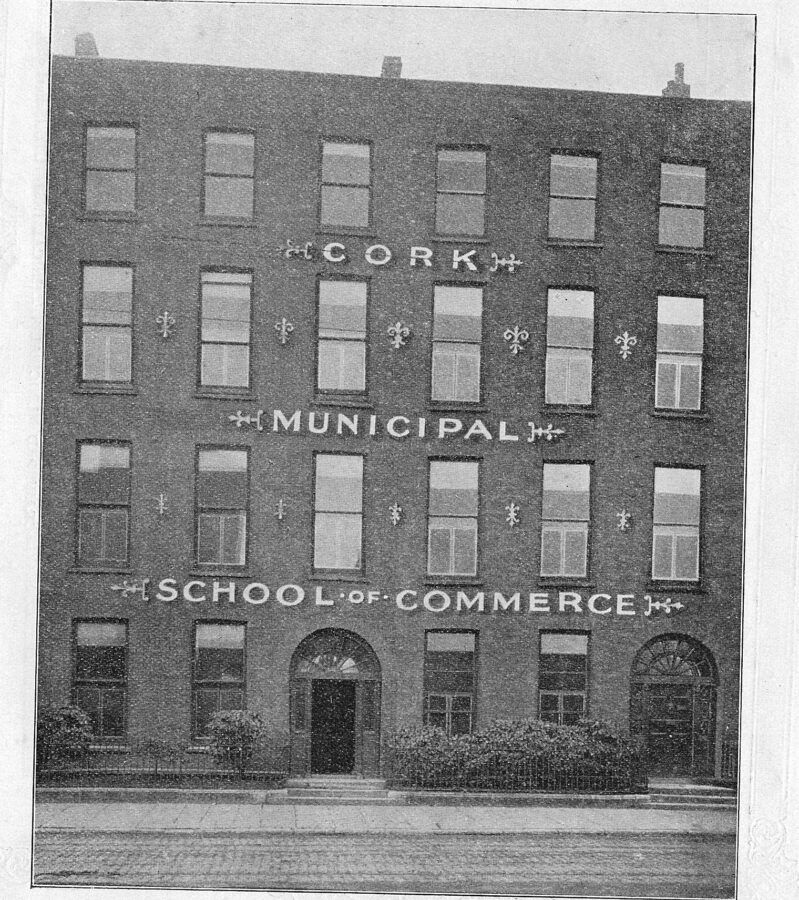

In the decade of the 1920s and against the backdrop of the emerging Irish Free State, the Cork Municipal School of Commerce was another institution, which pursued its programme for the future with dynamism. Since the School’s establishment in November 1908 in a former residential house on the South Mall, there had been steady improvements in aspects such as the intake of students, the average attendance, the School’s teaching programmes, the examination success of its students and also improvements in the post School opportunities of its students. In particular, in 1908 the School started with evening classes. In 1912-13 special afternoon courses were formed from 4 pm-7 pm. In 1923-24, morning courses were added.

Every year, the School of Commerce produced its year-end report and at the start of every School term in September, the report was read out at a public meeting and published in the Cork Examiner. In the 1920s not all of the annual reports were published but those that were offer a large insight into the workings and vision of the School. One such detailed report was published one hundred years ago in the Cork Examiner on 12 September 1924.

The seventeenth session of the Cork Municipal School of Commerce was formally opened on 11 September 1924. Richard Anthony, President of the Cork Workers’ Council, presided. He remarked that it was highly gratifying to find that 616 individual students had attended during the 1923-24 session compared with 526 for the previous one. In the public examinations there had been 544 successes as compared with 400 in the preceding session.

Mr Anthony pointed out there was a need for students to have a standard of primary education of senior grade, which would allow to fully benefit from the programmes of the School of Commerce. Arising from the standard of education issue, there were some students, who dropped out after a few weeks of commencing their course. The annual report detailed that in addition, the average percentage of actual to possible attendance was 66.

Mr Anthony also expressed that he hoped that Irish society would soon reach a stage in industrial and commercial prosperity when, instead of exporting their finished scholars and craftsmen, they would be able to “absorb into commerce and industry at home all the pupils trained in its School and in kindred institutions”.

The Principal of the School, D J Coakley, in submitting the annual report on the work of the School, said the complete return to peace following the Irish Civil War was reflected in the “increased entries and attendance and in the higher standard of work and general progress of the School”.

During the session, which extended from September to June inclusive, the teaching staff comprised the Principal, five full-time teachers and 17 part-time teachers. There were morning, afternoon and evening classes in business subjects. During the session 1923-24 a complete morning first year specialised course was introduced and this comprised commercial arithmetic, book-keeping, commerce, geography, Irish, shorthand and typewriting.

A scheme of Irish classes for teachers was established in the session 1919-20. Arrangements were made between the School of Commerce and the Munster College of Irish, by which the School took charge of the classes for members of religious communities and the Munster College made provision for lay Secondary and National teachers. Since these, classes were established they had an average yearly attendance of 60 teachers.

During the 1924-25 session the Cork Corporation struck a special 1d rate for the teaching of Irish in the Municipal Schools. This enabled the School of Commerce Committee to form in this subject four morning classes, two afternoon classes and six evening classes. The Irish classes, including those for teachers, had a total enrolment of 480 individual students. All the students in the morning and afternoon divisions took Irish as part of their course.

In order to cultivate an atmosphere of sound, oral Irish and Gaelic culture in the Municipal Schools the Committee awarded to the more advanced students eight scholarships of £10 10s each, tenable for the month of August, in a selected Gaelic speaking district, where a special Summer School of Irish had been formed.

In addition, as a result of a competitive examination in arithmetic, drawing, English and Irish held at the opening of the session, seventy free places were awarded in the introductory courses and forty-five scholarships valued at 15s each in the specialised courses. Indeed, from across all of the School’s courses, the total number of scholarships awarded in 1923-24 was 234, as compared with 160, 179, and 197, respectively, in the previous sessions.

The School of Commerce could also boast a successful employment bureau programme. To enable students to pass quickly from the study to the practice of business, a list of students wishing to obtain appointments, with full particulars as to their education and attainments, was kept at the School. On application from the employer one or more students could at once be selected for interview, either at the employer’s place of business, or by special appointment at the School.

D J Coakley also spoke about the inadequacy of the School of Commerce building to meet the growing requirements of the School. The School was located in an old dwelling house on the South Mall and the spaces for classes were very limited for expansion. He expressed the hope that ways and means could be found in the near future to remedy this serious drawback. However, it was going to be another decade though before the foundation of the new School was placed in 1935 on Morrison’s Island.

Whereas, from 1926-1930, the work of the School through the lens of the annual reports remains strong, in the 1926 report it reveals the introduction of an another notable feature. In September 1926 at the formal opening of the School term, the Constructive Thrift Movement in Cork was inaugurated. A special School Savings Committee was established and this comprised members of the School staff. Over 600 saving certificates were created during its first year.

Caption:

1273a. Cork Municipal School of Commerce as pictured in 1919 on Jameson Row, South Mall (source: Cork: Its Trade and Commerce available in Cork City Library).