Collaboration is Crucial:

The past few weeks coincided with Cork rated 24th in world rankings for quality of life. It is great to see Cork achieve such a global accolade – yes there are lots of challenges to tackle but a truckload of opportunities to keep pushing forward with as well.

In that light of positivity, it is important to note the work of many Cork entities who are pushing for a better quality of life and many of which are working with each other to make sure any collaboration opportunities are maximised. Cork City Enterprise Office in collaboration with my own Lord Mayor’s office recently celebrated the contributions of several local entrepreneurs, who contributed to a new online guidebook on enterprise development.

Entitled “Business Development in Cork: An Entrepreneur’s Guide, 2023” it is the first of its kind nationally and provides an extensive overview of the range of supports available from key stakeholders including Cork City Council, Cork County Council, Enterprise Ireland, The Local Enterprise Offices, Cork BIC, University College Cork, and Munster Technological University.

The case studies included highlight best practice across the different stages of business development, pre-start, start and growth stage. The case studies provide some excellent examples of the creativity and resilience of Cork citizens who are making a significant difference by providing much needed jobs, products and services.

Ultimately, the downloadable publication aims to assist entrepreneurs and businesses in Cork to navigate the wide range of financial and non-financial supports available at all stages of development. get in touch with Cork City Local Enterprise for more information.

Pure Cork:

A second online collaborative platform of note is the Pure Cork website It is a one stop shop to help anyone interested – locals and tourists – exploring what activities are going on the city and the wider region. Pure Cork is a strategic project, which began in 2015, and which set out to brand Cork as a visitor destination.

The strategy is led by Cork City and County Councils and a high-level Tourism Strategy Group. There is a collaborated vision and action plan, which gives cohesive direction to the future growth of tourism in Cork. This process is supported by Fáilte Ireland.

Cork Sports Partnership:

A third online collaborative platform of note to check out is that of Cork Sports Partnership. Their website and social media showcase a wide range of actions with the aim of increasing sport and physical activity participation levels in local communities across Cork. They work closely with the sports division of Cork City Council and together organise some really great summer sports activities in the city’s parks and public greens in housing estates.

The Partnership works closely to develop clubs, coaches and volunteers and support partnerships between local sports clubs, community-based organisations and sector agencies. They create greater opportunities for access to training and education in relation to sport and physical activity provision. They provide targeted programmes, events and initiatives to increase physical activity and sport participation. They also provide information about sport and physical activity to create awareness and access.

Meeting Notes from the Lord Mayor’s Desk:

My social media at present is filled with short interviews with people I am meeting. It is a personal pet project I call #VoicesofCork, which over the next few weeks and months will build into not only a mapping of the diversity of the work of the Lord Mayor but most importantly also to give a voice to a cross-section of those I meet.

17 July 2023, A visit to the Old Cork Waterworks Experience to chat to Manager Mervyn Horgan who spoke about the heritage venue’s historical context & its present day science work with Cork students.

17 July 2023, A Voices of Cork interview with Ciara Brett who is Cork City Council’s Executive Archaeologist and who has been researching & helping with the conservation of Elizabeth Fort for many years.

18 July 2023, A visit to Cork City and County Archives to Brian Magee who is Cork City Council’s Chief Archivist at Cork City & County Archives. The archives is one of the city’s & region’s collection points for historical documents, photographs & ephemera. Read more on their fab website.

18 July 2023, My Irish dancing is very rusty but good fun was had in Blackrock Community Association with MC Carmel Hatchell, music provided by Douglas Comhaltas, & it all ended with a cup of tea & some cakes. Community life in Cork rocks as always.

20 July, An afternoon launch of new outdoor callisthenic gyms, which are installed by the Council across the city. Calisthenics is a workout that uses a person’s body weight with little or no equipment. Eight of the thirteen outdoor gyms are now open with the remainder under construction.

20 July 2023, I was honoured to launch the “Era of kind-heartedness, an art exhibition by Oksana Lebedieva at Cork’s Hideout Café. Oksana expressed her thanks by the welcome she has received since coming to Cork from Ukraine.

20 July 2023, A trip to the Cork Arts Theatre to see the amazing Cora Fenton and Ciarán Bermingham in the play Fred and Alice. This standing ovation play is written and directed by John Sheehy.

21 July 2023, I was delighted to receive Cork, Estonian and Greek students on an EU Erasmus Plus project. Their central theme was music collaboration.

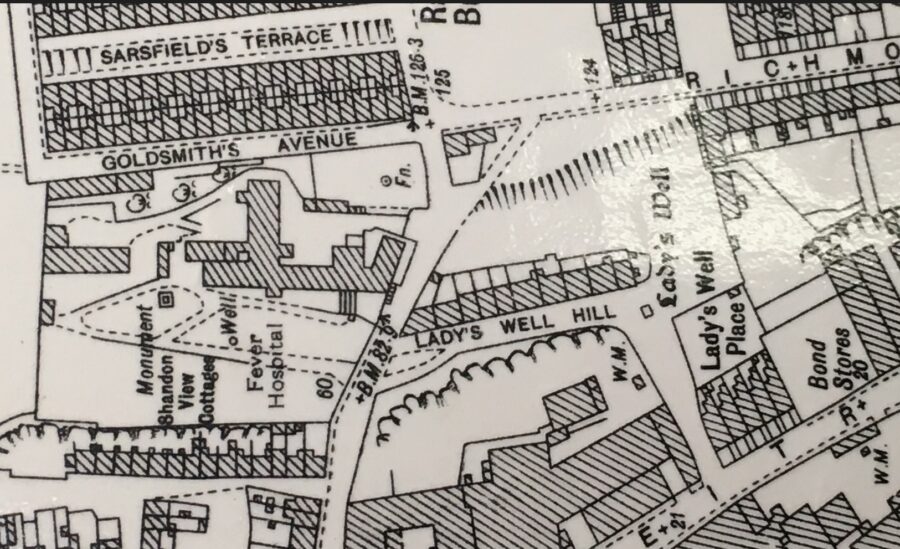

21 July 2023, The fourth of five Lord Mayor’s historical walking tours for July took place on Shandon area & its history – from its famous churches to the butter market story to the shambles, and the streetscape development. Discover more of my tours under heritage tours on my www.corkheritage.ie website.

21 & 22 July 2023, It was great to visit the garden parties of Care Choice, Montenotte & Farranlea Community nursing unit in Wilton, respectively, and even sing for a few moments.

23 July 2023, Family fun activities continue in Cork’s Fitzgerald’s Park with a fab array of music headliners! The annual Joy in the Park is always a big gem in Cork’s cultural calendar, and I was delighted to launch the day of activities.