Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 21 September 2023

Recasting Cork: The Naming of Griffith Bridge

A year after the deaths of Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith (August 1922) respectively, in August 1923, proposals to remember their legacy began. One such proposal to remember Arthur Griffith through the renaming of North Gate Bridge in his name drew the criticism of some Corkonians in September 1923.

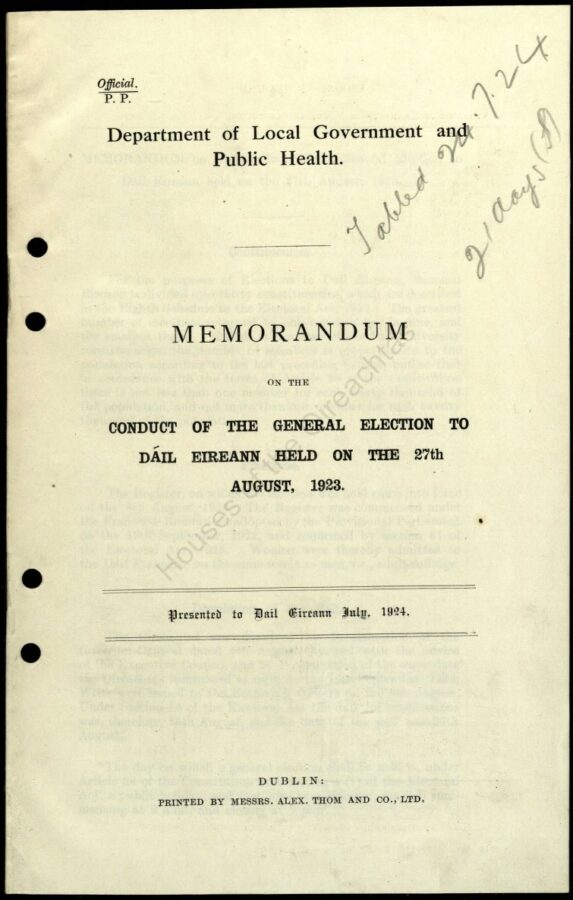

In mid-September 1923, the Cork Examiner records that at a meeting of Cork Corporation, Cllr M J O’Callaghan moved that the name of the historic North Gate Bridge, which was then a cast-iron structure, be changed to that of Griffith Bridge. Cllr Allen seconded and there being no opposition the motion was unanimously agreed to. Arthur Griffith was a writer, newspaper editor and politician. He established the political party Sinn Féin. He was the head of negotiations that created the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty. He was President of Dáil Éireann from January 1922 until his death later on 12 August 1922.

Criticising the decision was Dr Denis P Fitzgerald of Summerlea House in Tivoli. In a letter to the Cork Examiner on 17 September 1923, whilst respecting the legacy of Arthur Griffith the doctor wrote that old names of Cork should be kept and not forgotten about; “I am second to none in admiration of the late Arthur Griffiths as a Corkonian but I must enter a protest against the changing of the name of the bridge marking a very ancient and historical site of old Cork. Other memorials (and are they needed?) could be sought for and obtained to keep fresh the memory of a truly great Irishman, but it is a pity – and to my mind gross vandalism – to obliterate names associated with our city’s past”.

Dr Fitzgerald was clearly a lover of Old Cork and further pens in his letter that the memory of North and South Gate Bridges should be celebrated; “To any lover of Old Cork, with its canalled streets, castellated walls, and its North and South Gates, such obliteration of old associations is to be deplored. To retain in a material way the memorials of a city’s past is not often feasible, but surely it is a truly civic virtue to perpetuate, as far as possible names hallowed with the memories of the days gone by. It is to be hoped some member of the Corporation will take this matter in hand and let Cork’s citizen’s now and for ever have their North Gate Bridge”.

Another hard hitting letter by an anonymous writer with the pen name, Up Cork, published in the Cork Examiner on 19 September 1923 wrote about the irony that the proposals to change the name were made by members of a Council who did not support Arthur Griffith and the fall out of the Anglo Irish Treaty debate; “Sir, — every right minded citizen will endorse the protest made by Doctor Fitzgerald against the outrageous action of the Corporation in changing the name of North Gate Bridge. Arthur Griffith deserves to be honoured, but is it not cruel irony that this should be attempted by a body who helped to break his heart, and reduced this city to the level of a country town. The practical recognition of Arthur Griffith’s work is the finest tribute we can pay to his memory. It is, therefore, degrading that this his name should be used as a catch vote by petty politicians, who ignore civic traditions and the responsibilities of civic life”.

North Gate Bridge has a rich history and its development even till 1923 was layered. In the time of the Anglo Normans establishing a fortified walled settlement and a trading centre in Cork around 1200 AD, North Gate Drawbridge formed one of the three entrances –South Gate and Watergate being the others. North Gate Drawbridge was a wooden structure and was annually subjected to severe winter flooding, being almost destroyed in each instance.

In May 1711, agreement was reached by the Council of the City that North Gate Bridge be rebuilt in stone in 1712 while in 1713, South Gate Bridge would be replaced with a stone arched structure. The new North and South Gate bridges were designed and built by George Coltsman, a Cork City stone mason/ architect.

Between 1713 and the early nineteenth century, the only structural work completed on North Gate Bridge was the repairing and widening of it by the Corporation of Cork. It was in 1831 that they saw that the structure was deteriorating and deemed it unsafe as a river crossing for horses, carts, and coaches. Hence in October 1861, the plans by Cork architect Sir John Benson for a new bridge were accepted. In April 1863, the foundation stone for the new bridge was laid.

The new bridge was to be a cast-iron structure with the iron work completed by Ranking & Company of Liverpool. It was considered a marvel of engineering science at that time and nothing was spared in its ornamentation even to the intricate gas lamps originally built upon its parapets. An ornate Victorian style was incorporated into the new structure with features such as ornamental lampposts and iron medallions depicting Queen Victoria, Albert the Prince Consort, Daniel O’ Connell, and Sir Thomas Moore, the famous English poet. The new North Gate Bridge was officially opened on 17 March, St Patrick’s Day 1864 by the Mayor John Francis Maguire in the company of Sir John Benson, the designer and Barry McMullen, the contractor.

Nearly 100 years later – circa 1960, the bridge would have to be reconstructed again due to structural engineering issues. The Cork Examiner records on 6 November 1961 that after a closure of two and a half it was completely reconstructed, and it was reopened by the Lord Mayor of Cork, Mr Anthony Barry, TD. The new and present day structure, which is 62 feet wide as compared with its predecessor’s 40 feet, replaced the old cast iron structure, which spanned the River Lee since 1863.

Caption:

1220a. North Gate Bridge, aka Griffith Bridge, c.1923 (source: Cork City Through Time by Kieran McCarthy and Dan Breen).

Kieran’s Upcoming September Tours (end of season, all free, 2 hours, no booking required)

Sunday 24 September (two tours), The Friar’s Walk; Discover Red Abbey, Elizabeth Fort & Barrack Street area, in association with Autumnfest on Douglas Street; Meet at Red Abbey tower, off Douglas Street, 11am.

Sunday 24 September, Shandon Historical Walking Tour; in association with Cork Walking Festival, meet at North Main Street/ Adelaide Street Square, opp Cork Volunteer Centre, 5pm.