KIeran’s Our City, Our Town Article, Cork Independent,

16 December 2010

In the Footsteps of St. Finbarre (Part 241)

A Munster Line Out

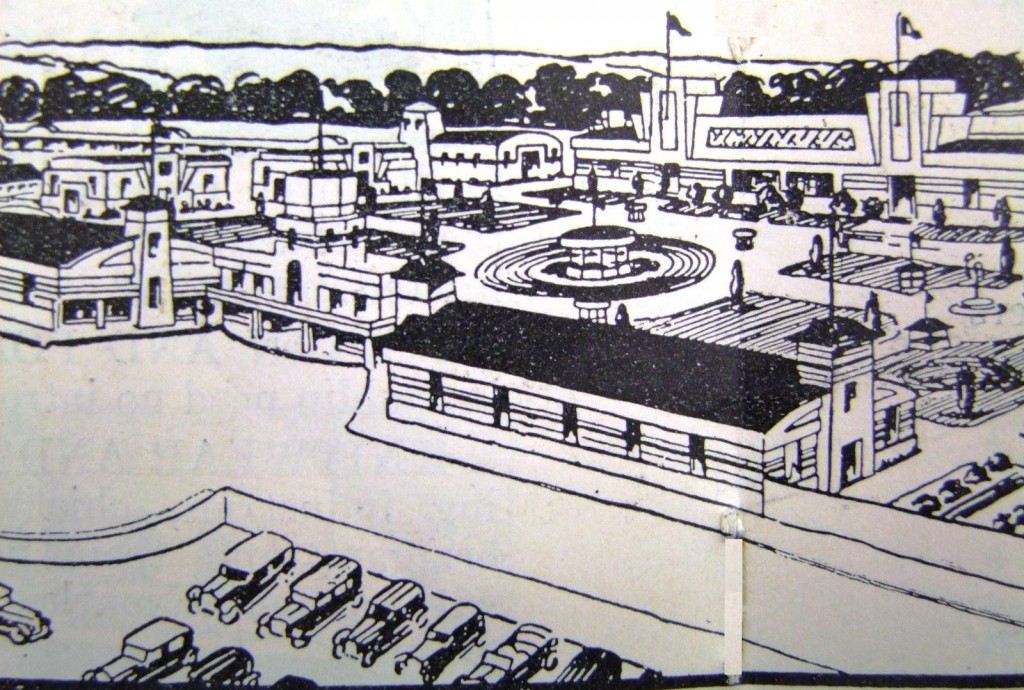

Continuing the walk through the Hall of Industry at the Irish Industrial and Agricultural Fair in Cork in 1932, stands number 30 to 32 were occupied by Joseph Hosford of 62 North Main Street, Cork. The Hosfords had a complete working exhibit showing the manufacture of jellies which were one of the principal products of the firm. Their general display of confectionery also included sponge rolls, slab cakes, barn bracks, boxed goods, silver wrapper cakes, corn flour and self-raising flour.

Stand number 33 and 34 were occupied by F.C. Porte & Co., 27 Marlborough Street, Cork, who exhibited electric lighting type crude oil engines as well as petrol paraffin engine and neon tube signs. Neon became very popular for signage and displays in the period 1920-1940. Neon lighting became an important cultural phenomenon in the United States in that era.

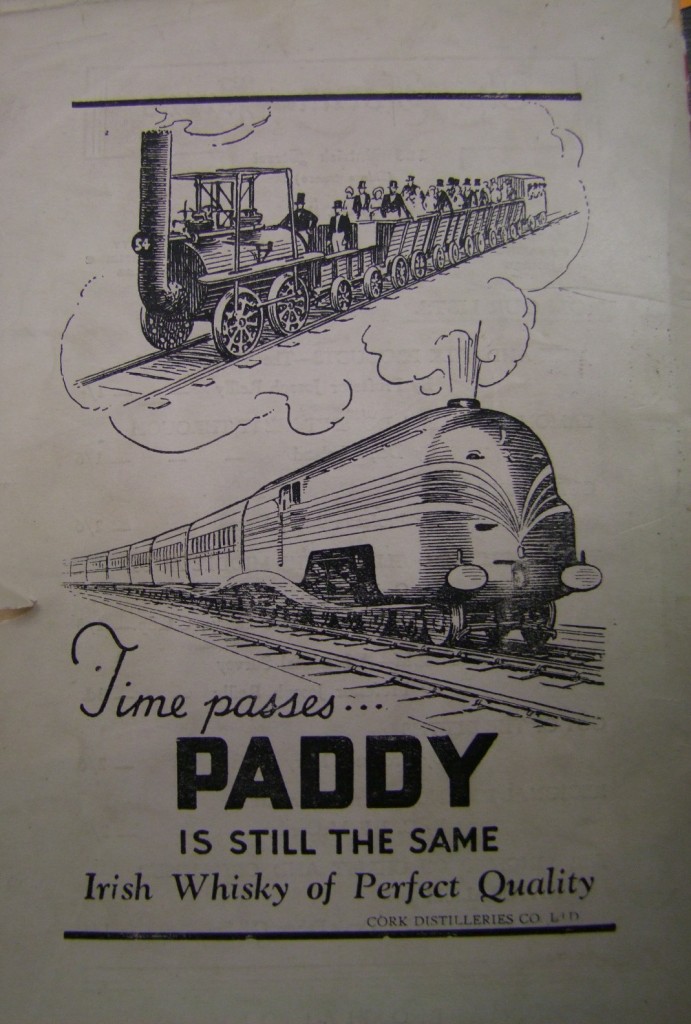

A number of strong Munster companies were also in the adjacent stand line-up. The display of Cork Distilleries Co. Ltd. was similar to that shown in previous international exhibitions at Philadelphia in 1876, Paris in 1878 and Sydney in 1879. It was in 1825 that the Murphy brothers founded the Midleton, Co. Cork. Distillery. That eventually became the home of all of the Company’s manufactured whiskeys, especially after they installed the world’s largest pot still with a capacity of 33,000 gallons. In 1867, the Cork Distilleries Company was set up when the Midleton Distillery amalgamated with four distilleries in the city. In 1880 over 400 brands of Irish whiskey were on sale around the world and more than 160 distilleries were in full production to meet the demand. In 1882 Paddy Flaherty joined the Cork Distilleries Co. Ltd and created the legend of “Paddy’s whiskey.” From 1919 to 1933 the Prohibition Laws in the USA decreed that all production, importation and trade in alcoholic beverages was forbidden. This had a devastating effect on the Irish whiskey industry. In 1921, the economic war with Britain meant that trade sanctions are imposed on Irish whiskey sales to the British Empire. Many Irish Distilleries closed as a result of this trade embargo.

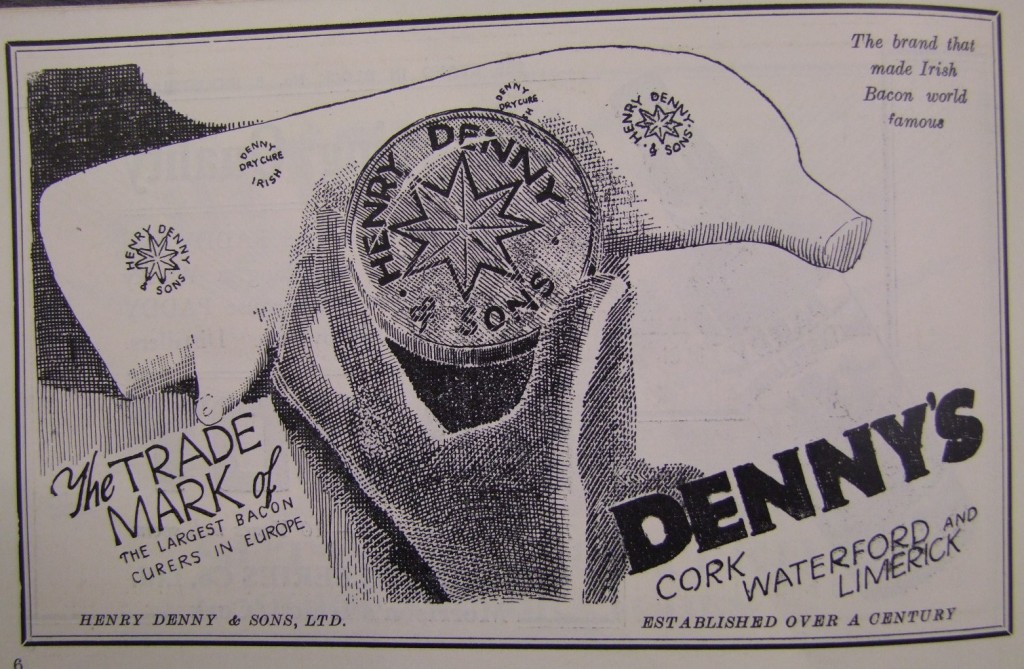

Next to the Cork Distilleries Co. was Henry Denny & Sons of Waterford. They showed bacon, hams, sausages, lard, puddings, cooked hams, luncheon sausages etc. Henry Denny started trading as a provisions merchant in Waterford in 1820 when he entered a partnership with a long-established general merchant. In 1880 Henry’s youngest son Edward set up Edward Denny & Co. in London and began expanding internationally. Between 1885 and 1900 it had operations in Germany, Denmark and America. A defining moment in the brand’s history arrived in 1933 at an International food fair in Manchester. Denny was awarded a gold medal for making the finest sausages. This accolade gave birth to the Denny Gold Medal brand.

W. & H. Goulding, Ltd., The Glen, had stand number 39 and exhibited sulphuric acid, superphostate and compound fertilisers, all manufactured in Cork. Goulding started making phosphate fertilizers in Cork in 1856. In 1969, the Glen was presented as an amenity area to Cork City Council by Sir Basil Goulding and is one of the best natural parks in Cork.

At stand number 45 was J.W. MacMullen & Sons, Ltd, George’s Quay, Cork. They staged an exhibit of their speciality “Parata” cooked maize. The fair catalogue notes that the George’s Quay plant had one of the most modern and up-to-date plants that could be divided for the manufacture of cooked maize. Messrs. MacMullen, in conjunction with their associated firm Messrs. Webb Ltd., of Mallow, were the sole contractors to the Co. Cork Poultry Keepers’ Association for poultry foods.. All information regarding different grades of foods was given. Both firms, MacMullen and Webb were also joint contractors to the Dairy Shorthorn Breeders Society for a specially prepared balanced ration. That was known as “Golden Cow” dairy ration, so blended in an effort to produce the highest possible output of milk.

In the Hall of Commerce, J.W Dowden & Co. had stand number one there. Their shop was at 113, Patrick Street, Cork. Originally a linen merchant, John Dowden had established a shop on Patrick Street by 1844 and the firm continued for well over a century. Members of the Dowden family were active in Cork life and in academic and church circles. Their exhibit at the fair comprised Irish linen products from bed spreads to dress linens and coats, costumes and dresses made to order. The men’s department exhibit comprised shirts, collars and pyjamas.

The Hall of Commerce was also the place where one saw a key enterprise from Limerick City. The Cleeves confectioners (Ireland) Ltd. Limerick took over six stand spaces. They were manufacturers of condensed milk, toffee and caramels. In 1860 Thomas Cleeve, a Canadian, travelled to Ireland to stay with his mother’s relatives who ran an agricultural machinery business in Limerick known as J.P. Evans & Company. Young Thomas decided to remain in Ireland and eventually assumed control of the business. In 1883, Cleeve started a new enterprise, the Condensed Milk Company of Ireland, in conjunction with two local businessmen. The business expanded to become the largest of its type in Ireland and the United Kingdom.

To be continued…

Captions:

570a. Advertisement for Denny’s, fair catalogue, 1932 (source: Cork Museum)

570b. Advertisement for Paddy’s Irish Whiskey, fair catalogue, 1932 (source: Cork Museum)

Today a reception was hosted in the Council Chamber, City Hall, Cork to mark the official naming of Mick Barry Road.

Today a reception was hosted in the Council Chamber, City Hall, Cork to mark the official naming of Mick Barry Road.