Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article

Cork Independent, 10 February 2011

In the Footsteps of St. Finbarre (Part 247)

Pictures at the Savoy

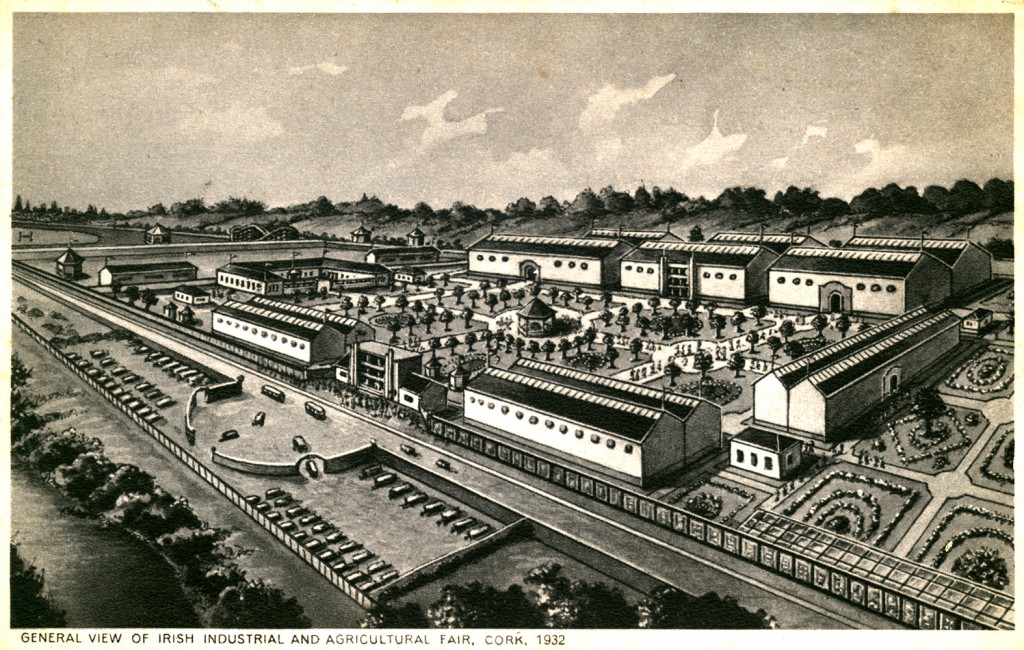

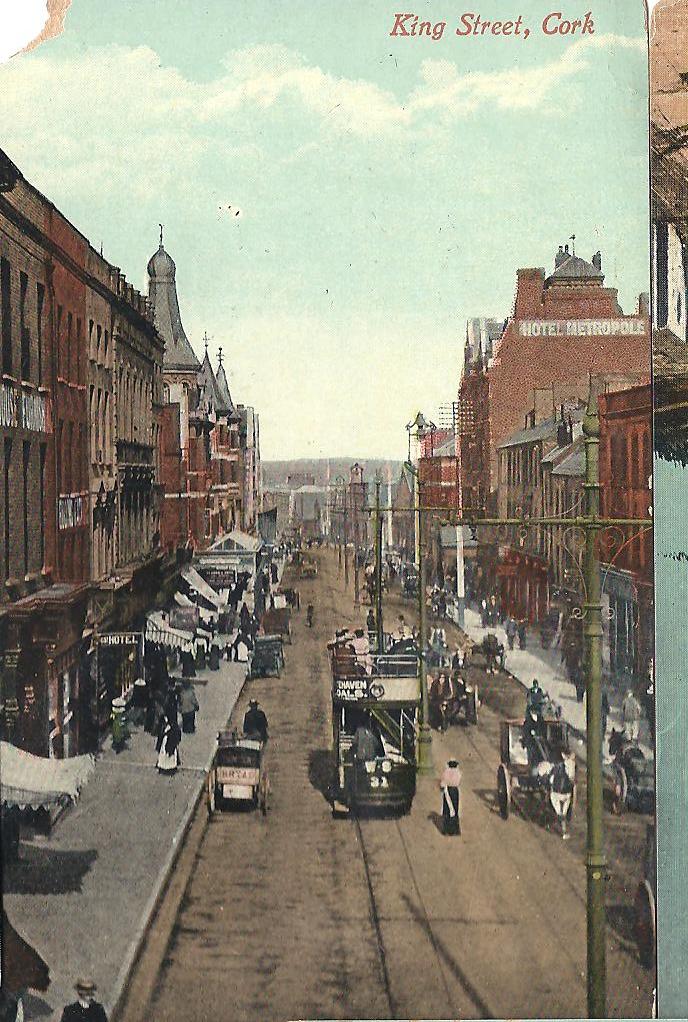

The summer of 1932 was a very eventful one for Cork. Apart from the Fair on the Carrigrohane Straight Road, Corkonians were also to witness the opening of the Savoy cinema on St. Patrick’s Street. That brought with it a sense of a modern dynamic like the fair that also captured the public imagination.

The cinema was another very popular form of entertainment in the 1920s. Indeed, it is difficult to disconnect the work of building a new Irish Free State and not perhaps comment on the influence of globalised entertainment venues like the cinema. For example, the Pavillion Cinema on St. Patrick Street opened in 1924 and popular silent movies shown there included Charlie Chaplain, Buster Keaton and Laurel and Hardy. In 1928 the first ‘talkies’ (films with speech) were made. In the post Wall Street collapse era of the early 1930s, the uncertainty of the time resulted in widespread popularity of fantastical and escapist cinema fare.

Newspaper coverage in the Cork Examiner on the 13 May 1932 has two pages full of insightful facts and figures about the Savoy cinema. The contractors of Cork’s Savoy cinema were the well-known firm of Meagher and Hayes, who were also responsible for the building of the Dublin Savoy cinema, which inspired the venture in Cork. The Cork building was completed in seven months from the time the foundations were laid. The labourers, skilled and unskilled, numbering about three hundred were all local hands with the exception of the workers of a few contractors. A total of 15,000 concrete blocks and close on 600 tons of steel work were used in the completion of the project.

The front of the cinema was executed in Hathern Faience of various colours. Its light-reflecting surface made flood lighting especially effective. It was manufactured and fixed by the Hathern Station Brick and Terra Cotta Co. Ltd or Loughborough, England, whose materials were extensively used for cinemas, hotels, business premises, shops, churches, etc. The cement used during the building of the premises was supplied by Norman McNaughton and Sons, Union Quay, Cork, and W.J. Hickey, Maylor Street, Cork and Charles Tennant and Co. Ltd., Cork and Dublin. The paints and distemper used were manufactured by Harringtons and Goodlass Wall, Ltd., Shandon Paint Works, Cork. Their paint was also used for the fair buildings in the Straight Road.

The Savoy comprised modern cinema architecture of its day from ventilation systems to phone systems to the projection room. The lighting was run off the cinema’s own plant, built by J.D. Carey and Sons, electrical contractors, 58, South Mall. The decorative scheme was designed and carried out by a London firm which had a worldwide reputation for furnishing and decoration on the “atmospheric style”. The aim was to create as the Cork Examiner suggests the “realms of romance, colour and sunshine of Northern Italy”. In the auditorium, the tableaux and scenic work were painted by well-known artist, Mr. Oswell Jones. Quaint archways, trees, fountains to images of magnificent scenes of the Grand Canal at Venice were painted on the walls.

Processioned seating assured that the occupier of every seat had an unobstructed view of the ‘picture’, projected on to the 40 feet long by 30 feet high screen. The well-known Cork firm, the Munster Arcade, completed the 2,500 luxuriously upholstered seats in moquette and as the journalist notes: “the colours being a perfect blending of grey, rose and blue”. The carpeting was done by this firm and the entire floor space was covered with Walton carpets in soft shades of rose. The Munster Arcade supplied the stage curtains (and their borders were of heavy satin in shades of gold and tango) as well as other curtains in other spaces in the cinema. The same firm also did the order for the uniforms and caps for the male attendants.

The opening ceremony was officially performed by the Lord Mayor, Cllr. Frank J. Daly. He spoke about Cork people having confidence in themselves and in their country. The resident manager was introduced, Mr. J. McGrath, a native of Roscommon. The General Manager was Mr. F.C. Knott, who was long established in Dublin as an entertainment provider. Mr. Hugh Margey was Catering Manager. Miss Kathleen O’Brien was the Restaurant Manager. For the operation of the Crompton organ in the auditorium, Mr Frederick Bridgeman was engaged. He had a nationwide reputation and was the Savoy’s top live entertainer for nearly thirty years. The attendants were recruited locally and employment was given to about seventy people. The Studios of Rank, United Artists, 20th Century Fox and Columbia supplied new films to the Savoy and the programme changed twice a week on Sundays and Wednesdays.

In 1953, the Cork Film International Festival, originally called ‘An Tostal’, began. For one week each year, the Savoy was home to the festival. By 1970, the character of the Savoy was starting to fade. The departure of Fred Bridgeman signalled the end of the era of the cinema organ and the grand sing-a-long shows. In July 1973, the Savoy cinema closed. Today, part of the Savoy is a shopping unit complex with the old cinema site a night club.

To be continued….

Captions:

577a. Advertisement from Dowdens celebrating the Savoy’s opening (source: Cork City Library)

577b. Façade of Savoy on St. Patrick’s Street, February 2011 (picture: Kieran McCarthy)

Today a reception was hosted in the Council Chamber, City Hall, Cork to mark the official naming of Mick Barry Road.

Today a reception was hosted in the Council Chamber, City Hall, Cork to mark the official naming of Mick Barry Road.