Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 1 November 2018

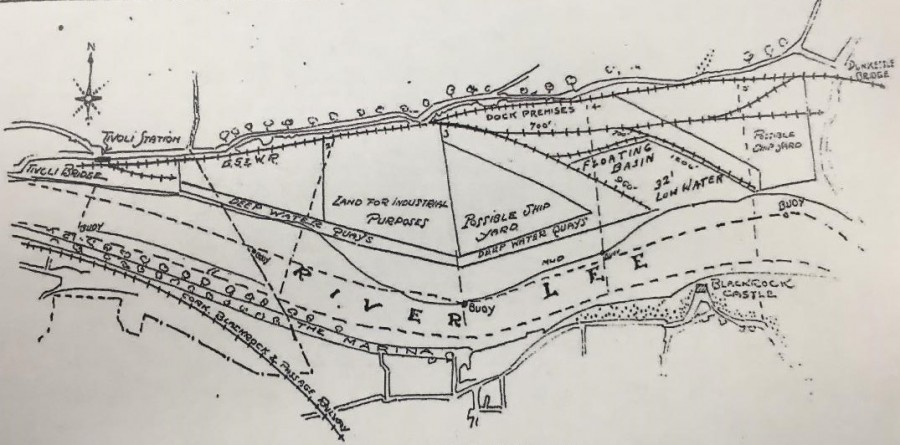

Stories from 1918: The Tivoli Reclamation Plan

During and up to the early years of the twentieth century campaigns by leading business organisations such as the two Chambers of Commerce (Incorporated and General) in Cork City and by the Cork Harbour Commissioners were ongoing for berths to be deepened at low water to keep all shipping afloat at the lowest tides. In 1918 the Cork Harbour Commissioners entered into discussion with the Board of Trade to acquire circa 155 acres of slobland at Tivoli for the purpose of pumping dredged material ashore, thus creating new land for industrial purposes. It was a project, which took many decades to come to fruition with the first ten years fraught with extra reports and land reclamation only beginning. In terms of history repeating itself in the last fortnight alone the Port of Cork has published new draft plans for the area, in light of the Port moving down river to Ringaskiddy.

On 6 November 1918 a function took place to inaugurate the Cork Harbour Improvement Scheme at Tivoli. The Chairman Mr D J Lucy and members and officials of the Cork Harbour Board, accompanied by many citizens, left the Custom House quay on board the ship Innisherrer. On arrival at Tivoli the ceremony was performed by D J Lucey. The speeches are outlined in the Cork Examiner of the day.

The proposal for reclamation of this portion of the riverside, or embankment, aimed to create a landbank, which would exclude the tidal waters from a tract of no less than 155 acres of slobland, extending from Tivoli to then existing Dunkettle Railway Station, a distance of two miles. The plans provided for the construction of quays on the foreshore at Tivoli Station, consisting of 500 feet of shallow water, berthage for trade, 700 feet of deep-water quay for the import trade, with an approach road, and with storage areas for which rents could be charged. Railway sidings were also proposed to be provided in connection with the quay, through liasing with the Great Southern and Western Railway Company, who already had a line to Youghal and a branch line to Queenstown (Cobh). The object of the extra depth at the deep-water wharf was to provide an extra 25 feet at low water – so that vessels of 16,000 tons carrying capacity could be accommodated. Vessels of 600 feet in length would also be able to swing from the wharf and then proceed to sea.

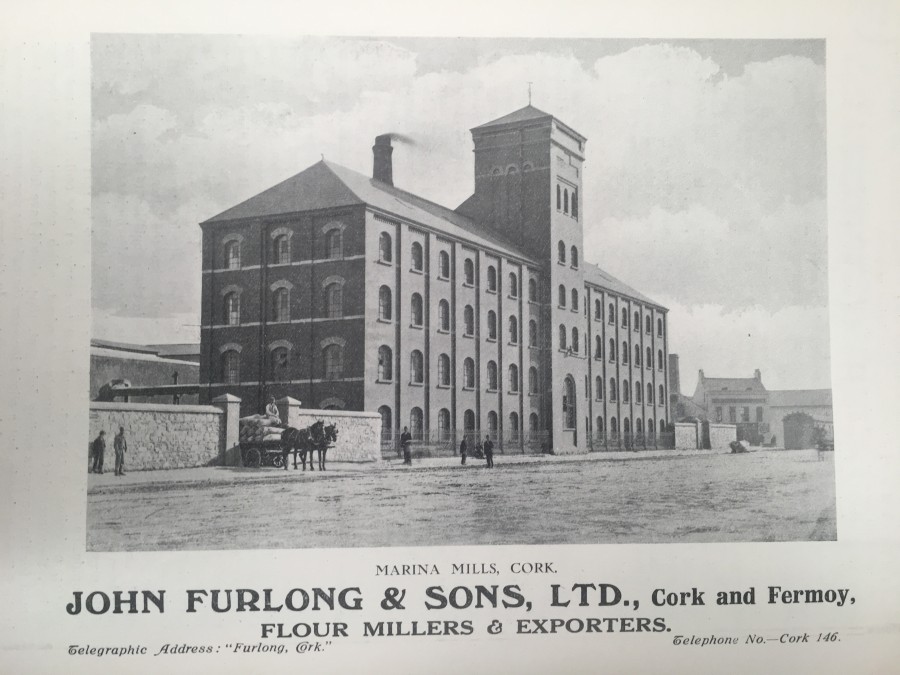

The chairman D J Lucey was excited about the proposals. He highlighted that the proposed new scheme aspired to open up an entirely new area for the development for the Port of Cork. He deemed the scheme to be of the most far-reaching importance to Cork, as it would not alone vastly improve and develop the port, but it would provide much needed employment for Cork people. He asked that the Great Southern and Western Railway Company assist, encourage and facilitate the scheme especially the new sidings required. The existing Dunkettle railway station had been overcrowded for some time, and any scheme that would improve that situation would be most welcome. It was estimated that the time occupied in the carrying out of the scheme would be about 15 years and the financial outlay of £24,000 would be provided as follows – £10,000 received from the Ford Company for the concrete wharf on the Marina, and the balance from the Cork Harbour Board’s Reserve fund.

The Chairman outlined that coal was cheap and the work could be done at a cost of 3d per ton with this expense deemed small in the overall scheme of work. The heavy coal bill of sending dredging material to sea could also be dealt with. The land could also be used for building ground after one-year post reclamation.

The Tivoli Reclamation Scheme was the brainchild of Cork Harbour Engineer James Price. In his obituaries in the Cork Examiner on 29 September 1936 and on 1 October 1936, they describe that he was born in Dublin and came to Cork when he was quite a young man with his father, who was at one time the President of the Institute of Civil Engineers. James was appointed Harbour Engineer by the Cork Harbour Commissioners in the 1890s and devoted his talents for close on forty years to the improvement of the port. Under his guidance many important changes took place. His first task on taking up his appointment was the difficult one of widening and deepening the channels of the Lee, and it was with this end in view that he recommended the purchase of the Lough Mahon dredger and the two large hoppers. Before the dredger began this project only comparatively small ships could come up the river channel to the quays at Cork.

It was James Price too who planned and built the wharf to the east of the South Jetties, which was subsequently sold to Messrs Henry Ford and Son and which was an important factor in inducing that them to set up a factory in Cork. Another important work carried out under Mr Price’s guidance was the erection of the well-known concrete wharves at the South Jetties, 1,200 feet long, of which thirty feet of water was available at low tide.

Kieran’s new book, Cork in Fifty Buildings (2018, Amberley Publishing) is now available in Cork bookshops.

Kieran is also showcasing some of the older column series on the River Lee on his heritage facebook page at the moment, Cork Our City, Our Town.

Captions:

970a. View of Lough Mahon from Tivoli, c.1840 – black and white engraving shows a view across the estuary from the city’s northern suburbs. It was produced by George K Richardson (fl.1833-1846) for the book The Scenery and Antiquities of Ireland (1840-1842).

970b. Plan of Tivoli Reclamation Scheme, 1929 by James Price & Cork Harbour Board