Category Archives: Landscapes

Ballinlough Summer Festival, 31 August 2024

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 29 August 2024

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 29 August 2024

Ronnie Herlihy Pocket Park at Langford Row

In recent weeks, Douglas Street Business Association in conjunction with Cork City Council launched a new pocket park at Langford Row. The park is in memory of the late Ronnie Herlihy, Local Historian, who wrote and gave walking tours across the South Parish. The new pocket park contains some of his writings on information panels.

The park is about unlocking more of the sense of place of the South Parish and sending people into a parish as Ronnie describes in his books “where you’ll find something of historical interest around almost every corner”.

In publishing his first edition of his South Parish book in 2003, Ronnie writes that he was aiming to do two things. Firstly, the book was simply meant to be a place one could go if they were interested in the rich heritage of the South Parish. Ronnie describes his work as, “a sort of one-stop-shop if you like, compiling between the covers of one book a list and some basic information about many of the historic places within the present parish, rather than having to search out the numerous different publications that contain articles or reports on those places”.

Secondly, Ronnie was hoping to awaken in people, no matter where they live, an awareness of their own surroundings, and “to get them thinking of the fantastic history all around them that has led to the making of this great City of Cork”.

Ronnie describes that all 1,000 copies of the initial South Parish book were sold. In the process €7,300 was donated to the Children’s Leukaemia Unit in the Mercy Hospital, being all the proceeds received from the sale of the book.

Ronnie undertook a second edition because of the number of times people asked him if the book was still available to buy. So, he published a second, revised edition. In doing a revised edition, it afforded Ronnie the opportunity to expand on many of the items in the original book. In Ronnie’s new introduction he quotes; “Having spent over 44 years either living or working in the heart of the South Parish, the area is in my blood. I’m still fascinated by the history of this part of Cork City, and as a proud member of the Cork South Parish Historical Society. We know that learning about the history of our own place is a never-ending process. Take a walk with me now in my own place, the open air museum that is the South Parish”.

The ‘awaken in people’ and the connection methodologies served Ronnie well in his next publication journey where he took on Victorian Cork. As he researched the South Parish, he spotted other nuggets of stories from Cork’s Victorian past, which took him off on another adventure.

Known as Victorian Cork, the book looked at events that occurred during the early Victorian period, from 1837 to 1859. The publication sought to as Ronnie noted “throw a little light onto the past, allowing the modern reader the opportunity of peering through the eyes of their Cork ancestors. It will hopefully give them a glimpse of a city that would only have been familiar to their grandparents, great-grandparents or great great-grandparents”.

The majority of the newspaper reports in his book were gleamed from the Cork Examiner, apart from the first few years between 1837 and 1841, when The Constitution or Cork Advertiser, was exclusively used. Where in our time it is easier than ever to use the digitised Irish Newspaper Archive from home, back in the day, Ronnie spent hour after hour, work lunchbreak after work lunchbreak turning physical newspaper pages and micro-film pages in Local Studies in Cork City Library.

Ronnie’s interest in people and their stories also brought him on his journey with his third book – this time returning to a physical space that of St Joseph’s Cemetery. The idea for writing this book followed on from research he carried out when he undertook a project on St Joseph’s Cemetery for the Annual Exhibition of the South Parish Historical Society.

That initial research, which looked at around two dozen burials in the cemetery, led to him as he quotes in his introduction spending many hours there in the summer of 2008, walking among the headstones of our ancestors, and “realising for the first time what an important historic gem we have here in the city”.

From that initial visit to research the project, as Ronnie explains in his introduction he was hooked. Ronnie followed that up by creating a powerpoint presentation that looked at the history of the cemetery, a number of those who are buried there, and some of the impressive monuments dotted around it. Afterwards, based on the presentation, Ronnie put together a walking tour of the cemetery. The next most logical step after that was to write a book.

In the immediate years leading up to his shock death, Ronnie’s interest in public history gathered further momentum. For many years Ronnie was a core part of the South Parish Historical Society annual exhibition – he was a core driver – and there was many a year he would spend hours and hours and hours involved in its organisation and its evolution

Ronnie’s adult education courses with Tom Spalding and others, regular phone ins with Neil Prendeville left many citizens wondering if they knew their city at all; it brought many citizens to Ronnie’s banner, so to speak, wishing to see the city through his eyes. In addition, there was his regularly gifting of photos and other snippets of Cork history to the world of Facebook.

The new pocket park is a fitting memory to Ronnie Herlihy – a great local historian but also a proud Corkonian.

Kieran’s September 2024 Tours, All free, 2 hours, no booking required:

- Sunday 1 September, The Friar’s Walk in association with Douglas Street Autumnfest; Discover Red Abbey and Barrack Street area, Meet at Red Abbey tower, off Douglas Street, 12noon.

- Sunday 8 September, Blackpool: Its History and Heritage; meet at square on St Mary’s Road, opp North Cathedral, 2pm.

- Saturday 14 September, Cork South Docklands; meet at Kennedy Park, Victoria Road, 2pm.

- Saturday 21 September, Fitzgerald’s Park: The People’s Park, meet at the park band stand, 2pm.

- Sunday 22 September, Stories from Blackrock and Mahon, meet in adjacent carpark at base of Blackrock Castle, 2pm.

Caption:

1268a. Ronnie Herilihy Pocket Park, Langford Row, Cork (picture: Kieran McCarthy).

1268b. The late Ronnie Herlihy.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 1 August 2024

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 1 August 2024

From Source to Sea at the Crawford Art Gallery

One of the last exhibitions before the revamp of the Crawford Art Gallery celebrates the River Lee. The exhibition is entitled From Source to Sea and is on from 22 June to 22 September in the Gibson Galleries at Crawford Art Gallery.

The exhibition following the course of the River Lee, from its origins in the Shehy Mountains and Gougane Barra in the west to its meeting with the Celtic Sea at the mouth of Cork Harbour in the east, has opened at Crawford Art Gallery. Spanning historic and contemporary artworks from the collection, From Source to Sea celebrates the culture of Cork’s mighty Lee and its tributaries.

Artworks from the 1750s through to the present day are featured in the exhibition. Each painting, drawing, print, and sculpture offers a perspective on the river, the stories it has carried and collected, the places and people it has shaped, and the changes it has inevitably borne.

The exhibition features much-loved paintings, ranging from John Butts’ View of Cork from Audley Place (c.1750) and Whipping the Herring out of Town (c.1800) by Nathaniel Grogan, to George Mounsey Wheatley Atkinson’s Paddle Steamer Entering the Port of Cork (1842) and Skellig Night on South Mall (1845) by James Beale. These are joined by the work of artists Sarah Grace Carr, Kate Dobbin, John Fitzgerald, Robert Gibbings, Patrick Hennessy, Seán Keating, Diarmuid Ó Ceallacháin, and George Petrie.

Recent acquisitions by Ita Freeney, Bernadette Kiely, and Donald Teskey offer new contexts, while portraits by Séamus Murphy, Nano Reid, and Eileen Healy recall rich tales from the Lee Valley, including The Tailor and Ansty and the inimitable voice of Cónal Creedon.

In an overall sense, the exhibition encourages the viewer to reflect on the histories and perspectives of the River Lee Valley and to travel back from the city to the source in the Shehy Mountains. Michael Waldron, curator of the exhibition, says: ‘Following our popular exhibitions focusing on Cork city and harbour, it’s been such a pleasure to take a journey along the River Lee itself. I hope visitors will take as much enjoyment in following its course, connecting with the river’s rich history and culture, and maybe even get inspired to take their own stroll at Gougane Barra, Lee Fields, or the Marina”.

It has been over a decade since this column chronicled histories from the Lee Valley and recorded many oral histories from life within it. Some of these stories I have placed up on my website www.corkheritage.ie. At the time, I wrote that the origin of the name Lee is sketchy and legend reputedly attributes the name to an ethnic group known as the Milesians from Spain who reputedly arrived in Ireland several thousand years before the time of St. FinBarre. Legend has it that the Milesians acquired land in Southern Munster, which they named ‘Corca Luighe’ or ‘Cork of the Lee’ from Luighe, the son of Ith who attained the land after the Milesian advent to Ireland.

In addition, the River Lee – An Laoi over the centuries has had many variations in its spelling. In early Christian texts such as the Book of Lismore, it is described as Luae. It has also been written as Lua, Lai, Laoi and the Latin Luvius. An entry in the Annals of the Four Masters in the year 1163 A.D. names the River Sabhrann. However, many scholars agree on the name Lee as the most common name of the River.

The columns from over a decade ago also reflected upon the rich heritage of Gougane Barra. Most notably and grabbing the visitor’s eye at the start of the Crawford Art Gallery exhibition is a hand coloured and beautiful acquatint by Newton Fielding entitled “Gougane Barra Lake with the Hermitage of St Finbarr, County Cork”. It is a copy of George Petrie’s work.

George Petrie (1790-1866) was an important Irish landscape painter of his day. He explored people’s memories along with native Irish cultural traditions as he found them in the historic fabric of old monuments and buildings in the four corners of Ireland. He devoted himself to landscape painting in watercolours.

In 1819 Petrie supplied ninety-six illustrations for Cromwell’s Excursions Through Ireland. He subsequently furnished drawings for several publications, such as the Rev G N Wright’s Guide to Killarney, Guide to Wicklow and Historical Guide to Ancient and Modern Dublin, 1821, as well as Brewer’s Beauties of Ireland, 1825. Petrie’s appreciation of landscape was deeply indebted to William Wordsworth. He also had a constant awareness of the continuity between living folk art and antiquity. Petrie’s work explored the Irish landscape as a cultural echo informed by the lingering memories of native cultural traditions and antiquities.

Petrie’s work as a field officer with the Ordnance Survey of Ireland in the early nineteenth century was, according to art historian Peter Murray, an enormous salvage operation to collect and preserve the remains of Ireland’s native culture and identity. George Petrie’s Gougane Barra(one of two versions) attempts to put the viewer in the heart of the Shehy Mountains. Pilgrims/tourists seem dwarfed by awe-inspiring landscapes and give an increased interest and picturesque aspect to the scene.

Explore and rediscover the Lee Valley with From Source to Sea, whichis on from 22 June to 22 September in the Gibson Galleries at Crawford Art Gallery.

Captions:

1264a. Entrance to From Source to Sea, Crawford Art Gallery (picture: Kiran McCarthy).

1264b. Hand coloured and beautiful acquatint by Newton Fielding entitled “Gougane Barra Lake with the Hermitage of St Finbarr, County Cork”. It is a copy of George Petrie’s work.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 25 July 2024

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 25 July 2024

Donoughmore in the Spotlight

Recently Gerard O’Rourke’s new book Land War to Civil War 1900-1924, Doqnoughmore to Cork and Beyond hit the shelves of Cork book shops. It is a story of conflict and perseverance leading to Irish Independence. It explores, examines, and explains how this was achieved. The book recounts numerous incidents and experiences begins in Donoughmore stopping at various locations through to Cork City and internationally through the stories of the executions of Mrs Lindsay and Compton Smith, Mary Healy and Éamon de Valera, the Wallace Sisters, Dripsey Ambush, Civil War, executions, prison, life, sport, culture, economic life, and daily life.

In his introduction Gerard notes that the aim of the book is to chronicle and document the rise of nationalism and subsequent road to Irish Freedom using Donoughmore, an area 26 km north, north-west of Cork, as a source for investigation. It builds upon stories in Gerard’s second book Ancient Sweet Donoughmore: Life in an Irish Rural Parish (2015). These publications together with an earlier work A History of Donoughmore Hurling and Football Club (1985) completes a significant trilogy of the story of this ancient parish.

Gerard in his introduction further writes about the importance of researching the quest for Irish Independence; “There was a time when talk about what was termed the troubled times was not engaged in, was frowned upon, and brought up too many bitter memories. The advancement of time has changed this and by documenting the narrative of this period we are paying homage to our own. Their sacrifices and work are rightfully highlighted and gives us an insight and appreciation to what was ‘the hidden Ireland?. It more importantly brings context to what we all enjoy today, freedom, independence, self-governance, the scope to make decisions, pursue opportunities all manageable without external intrusion”.

For Cork City Gerard has a really great reflection chapter on the lives and times of Nora and Sheila Wallace, whose story on St Augustine’s Street and their part in the Irish War of Independence in Cork City has come more to the fore in recent years. Gerard draws on family archives including notes and correspondence from the Wallace Sisters. He writes that the Sisters were greatly influenced by tales of Fenians and revolution and a thirst for Independence. They were inspired by the foresight and writings of Pádraig Pearse and James Connolly. The sisters were further enthralled by the focussed and nationalist outlook of Countess Markievicz.

Indeed, Gerard outlines in his research that Nora paid a moving tribute to the countess on her death; “Her proud spirt had learned much or Kathleen Ní Houlihan, and the many ills that needed remedies. One noble heart, one gifted woman, laid aside all loves, and joys to serve her country. Her ideals demonstrated a desire to help the weak, and a firm belief that all difficulties could be overcome by hard work”.

When Countess Markievicz, was court martialled after the Easter Rising her action in kissing her revolver was dramatic as well as poignant. Nora commented on the fight to win; “We who know her, can appreciate fully, what that action implied; the love of a generous heart, and the belief that we should fight to win, coupled with the perfect discipline of a soldier”.

It was in 1911 that a branch of the Fianna organisation was established in Cork. Among those at the inaugural meeting was Tomás MacCurtain and Seán O Hearty. Later, Cumann na mBan was formed in Cork in 1914 and among the women who operated this organisation were Mary MacSwiney, Nora O’Brien, Bridie Conway, Annie and Peg Duggan and Nora and Sheila Wallace.

Gerard further outlines that Nora Wallace’s work with the Volunteers where she made first aid outfits and haversacks brought her increasingly into contact with Tomás MacCurtain and he trusted her with specific intelligence work. After the Easter Rising, she was given special instructions by Tomás to visit Michael Brennan Officer in Command of the East Clare Volunteers at Cork Prison.

In June 1917, the closure of the Volunteer Hall in Sheares Street created a problem for the IRA in Cork. Without a base or recognised meeting place the mechanisms were problematic to direct a war against the Crown Forces. Florence O’Donoghue, Adjutant of the Cork No. 1 Brigade and responsible for communicating with the Brigades units and further afield, saw the potential in using the shop of the Wallace Sisters as a depot for dispatches and a communications centre;

“A depot for dispatches was essential. We found it in the newsagents shop of the sisters Shelia and Nora Wallace…I had been getting my papers there and had known them for some time. They lived over the shop, they worked from eight in the morning until midnight…if any two women deserved immortality for their work…they did. Wallace’s became to all intents and purposes Brigade Headquarters…an indispensable part of the organisation. Shelia and Nora came to know everybody and everyone’s status; they became experts at side tracking persons with no serious business… nothing I could say about their tact and discretion would express adequately my appreciation of the manner at which they did a most difficult and valuable job”.

Gerard details through his research that it took until May 1921 for the British authorities finally tried to curb the actions of the Wallace Sisters and in a letter to the sisters an instruction was given to them to close the shop. Resilient as ever the sisters attained a temporary shop lease in the English Market and continued their work. Less than two months later following the Truce the shop was reopened.

Nora and Sheila Wallace took the Anti-Treaty side and when the Irish civil war broke out, they had to reconsider their activities given they were well known to their former comrades. In that respect despatches were moved promptly. The shop was constantly raided during this period.

€15 sold of each copy of Gerard O’Rourke’s Land War to Civil War 1900-1924, Donoughmore to Cork and Beyond will be donated to cancer care services in Cork.

Caption:

1263a. Front cover of Gerard O’Rourke’s Land War to Civil War 1900-1924, Donoughmore to Cork and Beyond.

Voices of Cork – From Source to Sea, 18 July 2024

Lord Mayor Cllr McCarthy Goes Poster Free, 11 May 2024

Ahead of the upcoming Local Elections on 7 June Lord Mayor of Cork Cllr Kieran McCarthy has gone poster free on poles across the south east local electoral area. Kieran noted; “I have been particularly inspired by the work of Douglas Tidy Towns who have advocated the non-postering of posters in Douglas Village. I also have a very keen and active interest and participation in promoting the environment and heritage in the city”.

“To those asking about if I am still running because they don’t see my poster – As an independent candidate I am very much in the race in this local election in the south east local electoral area of Cork City – I have been canvassing for several weeks at this moment in time. I won’t get to each of the over 15,000 houses in the electoral area, but certainly and against the backdrop of a very busy Mayoralty post, I am daily trying to knock on doors in the various districts of my local electoral area. My manifesto is online at www.kieranmccarthy.ie, which champions such aspects such as public parks, environmental programmes, city centre and village regeneration, and the curation of personal community projects such as my historical walking tours, concluded Kieran”.

Read my manifesto here: 2. Kieran’s Manifesto, Local Elections 2024 | Lord Mayor of Cork Cllr. Kieran McCarthy

Kieran continues his suburban historical walking tour series next Saturday 18 May, 11am with a walking tour of Ballinlough. The meeting point is at Ballintemple Graveyard, Temple Hill, 11am. The tour is free, two hours and no booking is required. Kieran noted of the rich history in Ballinlough; “With 360 acres, Ballinlough is the second largest of the seven townlands forming the Mahon Peninsula. The area has a deeper history dating back to Bronze Age Ireland. In fact it is one of very few urban areas in the country to still have a standing stone still standing in it for over 5,000 years. My walk will highlight this heritage along with tales of big houses such as Beaumont and the associated quarry, rural life in nineteenth century Ballinlough and the development of Ballinlough’s twentieth century suburban history”.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 9 May 2024

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 9 May 2024

Ballygiblin Memorial to Seán O’Donoghue

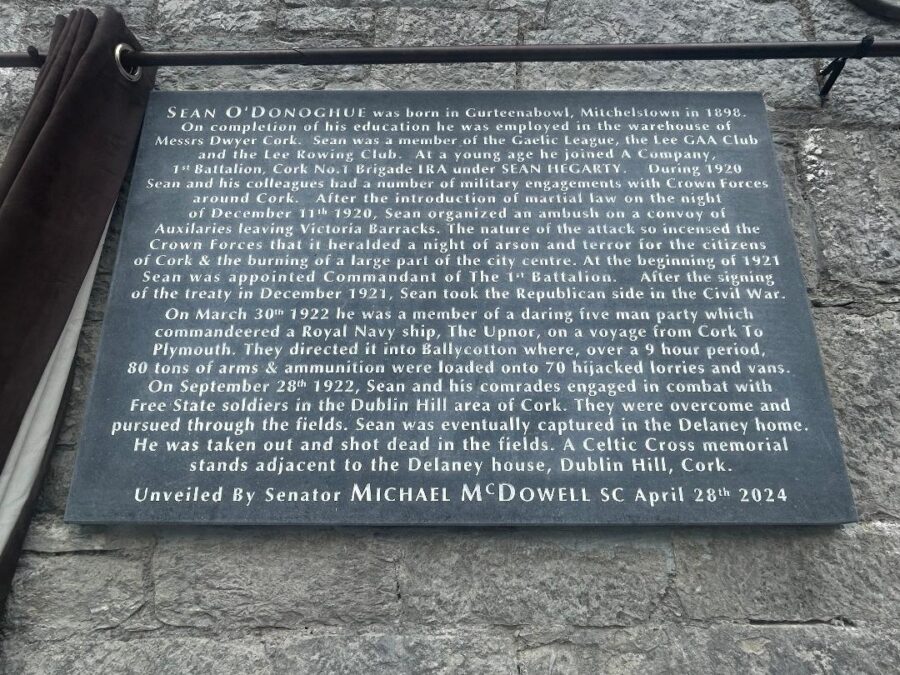

A new memorial has been unveiled in Ballygiblin, Mitchelstown to the memory of Seán O’Donoghue (1898-1922), Commandant of the Cork No.1 Brigade, 1st Battalion who was deeply involved in the Irish War of Independence in Cork City.

The associated memorial booklet is now on sale in book shops in Mitchelstown. The text compiled by the memorial committee outlines that baptised as John, Seán was born in Gurteenabowl, Mitchelstown in 1898. He was the 5th child born to his parents William & Nano (nee O’Mahony) O’Donoghue.

On completion of his education, he was employed in the warehouse of Messrs Dwyer, Cork and he lived with his aunt in Roches Buildings. Seán was a member of the Gaelic League, the Lee GAA Club and the Lee Rowing Club. At an early age he joined A Company, 1st Battalion, Cork No 1 Brigade, becoming Quartermaster of the company. He was subsequently promoted to Quartermaster of the Cork Brigade. At the beginning of 1921, he was appointed Commandant of the 1st Battalion.

A loyal and courageous officer, Seán was involved in several engagements with the Black and Tans in Cork and at the signing of the Treaty, he took the Republican side in the Civil War.

On the afternoon of Saturday, 11 December, the day after Martial Law had been declared, in the south of Ireland, Sean O’Donoghue received word that a party of Auxillaries travelling in two lorries would depart Victoria Barracks that night at 8pm. The report also mentioned the possibility that Captain Campbell Kelly, a British Army intelligence officer based at Victoria Barracks who was known to torture IRA prisoners, would be travelling with them.

The IRA considered Captain Kelly a major threat and were anxious to eliminate him. Armed with this information, O’Donoghue decided to act. Though time was short he managed to muster the following Volunteers: Michael Baylor, Seán Healy, Michael Kenny, Augustine O’Leary and James O’Mahony. He also sent word to Anne Barry to have the grenades ready. As darkness fell, she took them from her home and hid them in the front garden of a house owned by the Lennox family at Mount View on the Ballyhooly Road.

Under the cover of darkness, the men took up their positions behind the wall between Balmoral Terrace and the houses at the corner of Dillon’s Cross. Michael Kenny took up position at Harrington Square, on the opposite side of the road to the ambush party and within braking distance of the ambush position.

Michael Kenny wore a mackintosh overcoat, scarf and cap to give the impression that he was an off-duty British soldier. His task was to act as a lookout and to slow down the lorries as they approached the ambush position. At approximately 8pm, the two lorries, each containing 13 Auxillaries, left the barracks and drove towards Dillon’s Cross. As the leading lorry approached Harrington Square, Michael Kenny stepped out to the edge of the footpath, put up his hand and signalled the driver to stop. As he slowed down, the second lorry passed, Kenny gave the signal to the men behind the wall. He then made his escape to the IRA hideout in Rathcooney.

At the signal the ambush stood up and hurled bombs at their target. As the bombs exploded, they each drew their revolvers and fired at the Auxillaries, before making their escape. Seán O’Donoghue and James O’Mahony made their way to the Delaney farm at Dublin Hill. Seán was carrying the unused bombs and he hid these on the Delaney land. The two men split up and went on the run.

This ambush heralded a night of arson and terror for the citizens of Cork, culminating in the burning of a large part of the city centre.

The turbulence behind the Pro-Treaty and Anti-Treaty sides took a darker turn when across February, March and April 1922, the IRA, particularly Anti-Treaty elements, began to seize sizable amounts of weapons from evacuating British forces. The steamship Upnor was a small British Army stores carrier of about 500 tonnes deadweight. She was loading at the ordnance stores on Rocky Island with arms and ammunition from the recently disbanded Royal Irish Constabulary for Plymouth when Seán O’Donoghue and his comrades of the 1st Brigade, 1st Southern Division of the IRA got to hear of it.

A well organised and executed operation followed. On 29 March, the Upnor sailed. This was reported by intelligence sources in Cobh and the plan swung into action. The Admiralty tug Warrior, crewed mostly by local men was at the Deepwater Quay in Cobh. Her master was enticed ashore and Captain Jeremiah Collins, a master mariner, IRA officers – Seán O’Donoghue, Dan Donovan, Michael Murphy and Seán O’ Hearty boarded with some volunteers and took the ship to sea some hours after the Upnor.

By means of a ruse, they caused the Upnor to heave to and even though the Upnor‘s master was suspicious, he let them come alongside. Sean O’Donoghue and his contingent boarded and captured the ship and she was brought to Ballycotton at 4am on 30 March. Meanwhile a large number of lorries and cars had been commandeered and brought to Ballycotton. The town had been sealed off and when the Upnor arrived, she was quickly unloaded and her contents dispersed inland.

On 28 September 1922, a party of Irish Free Government’s National Army forces consisting of one officer and ten soldiers had been operating in the Carrignavar, Whitechurch and White’s Cross districts, carrying out searches. At approximately 3.45pm when they reached a point some two miles beyond Dublin Hill, Blackpool, and about a mile from the place where the motors were seized, they were ambushed by Seán O’Donoghue and his comrades, who were in occupation of strong positions and poured a hail of bullets in the direction of the National Army troops, who were forced to halt their cars and alight, proceeding to engage with Seán and company. A brief fight was sufficient to rout them and the soldiers pursued them across country for a considerable distance.

Sadly, Seán O’Donoghue was located, removed from the Delaney family home and killed by the Free State Government troops in a field nearby. His body was brought to Cork by the troops.

A Celtic cross memorial now stands near the Delaney family home at Dublin Hill, Cork. Commadant Seán O’Donoghue’s name is inscribed on this memorial. The new Ballygiblin memorial also recognises Seán’s contribution to the Irish War of Independence and the tragedy of the ensuing Irish Civil War.

Caption:

1252a. New memorial to Seán O’Donoghue, Ballygiblin, Mitchelstown (picture: Kieran McCarthy).