Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 19 January 2023

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 19 January 2023

Recasting Cork: A Vision for Refuse

Cork Corporation records from one hundred years contain very detailed reports on a myriad of topics. One report, which was published in January 1923 in the Cork Examiner, was a report on street scavenging and cleaning.

The report outlines that the system for refuse collection for the City of Cork was antiquated and had consequently given rise to many complaints by the citizens. The Corporation’s Public Works Committee wished to introduce a reorganisation of the dumping of refuse, mud and manure and to move towards a better efficient and more economic service.

There was difficulty to obtain satisfactory dumping grounds for accumulated refuse. The procurable sites in the city’s suburbs were often situated at too great a distance, while the passages leading to some of these grounds were steep and ill-kept. The contents of each cart were on average more than about 12 cwts in weight.

The collection and removal of the street mud, together with the removal of the street manure, was under the control of the Public Works Committee. The treatment of the domestic scavenging was placed under the jurisdiction of the Public Health Committee. Trade scavenging or refuse produced by traders was meant to be carried out by the inhabitants of the various shops and houses, but for the most part was directed to be carried out by the Public Works Committee. This Committee often struggled to cope with the amount of trade refuse and hence the overall result was disorganised.

The report recommended that there should be in the future one combined central committee of public works and public health, which would he held responsible for the competency of the whole refuse work programme. In addition the report proposed that the traders should pay a cost towards an efficient facility; “By this means it will be found that a systematic collection of paper, boxes, etc., can be satisfactorily dealt with, and the present exposure of such rubbish which, flies about the streets in windy weather obviated to the benefit and health of the citizens”.

The street cleansing staff worked across six defined geographical areas of the city with 40 men employed across winter, 41 men during the summer with 17 cart carriers in the winter and 14 cart carriers in the summer. Each of the areas included a ganger.

The report outlined that there was a certain number of older men who were employed and who had devoted years of work in the service of the Corporation. However, by reason of their ages they were unable to carry out a full day’s work. The report suggested that such men should be distributed amongst the younger men in the various areas, so as to support the spread of the heavier work across more able and younger staff members.

The lane-cleaning staff across five city areas comprised 25 men who swept the lanes the lanes of the city and collected the street manure. Eleven cart carriers assisted them in the taking away of what these latter staff collected. They were all under the direction of one ganger in each area.

The total number of loads of mud removed per month from the city’s divisional work area comprised 15,000 loads at 12 cwts, which came to 9,000 tons per annum. It was estimated that 50-60 tons of refuse excluding the mud were daily collected for dumping across the city’s suburbs, historically in a controlled way.

The report suggested that dumping barges could be placed upon the two branches of the River Lee and the city could be divided into suitable sections served by the necessary men and carriers to collect and convoy the material to the barges. The barges when filled could then be possibly carried down the river to one overall controlled tipping ground, which was possibly exist between Tivoli and Dunkettle, which at that time were going . The proposal noted: “If we assume that we must provide for the daily removal of 60 tons, and that such removal necessitates two sites on the North river and two sites on the South river, the capacity of each barge would be 14-15 tons, or even, perhaps, 20 tons, which would only entail a small vessel”.

If the barge suggestion was to be entertained, the report highlighted that two important points needed to be resolved – (1) the dust, which would arise when unloading into the barges, and (2) the rise and fall of the tide during the loading periods within the city’s quaysides. It would be necessary to furnish the barges with proper covers and convey the refuse from the carts into the barges through “covered shoots, constructed telescopically. in order to automatically meet the rise and fall of the tide, which would be of daily occurrence”.

The report detailed that any reasonable capital outlay necessary to introduce a successful method of dumping mud at a controlled space would cost roughly £17,000. In explaining the report, Mr Joseph F Delaney, City Engineer, said that the whole point in the scheme was the changing of the extent system of dumping; “where at present, loads were carried to far away places on the outskirts of the city, it was proposed to remove them to quayside stations, and thence have them convoyed down the river in barges to Tivoli, or some other suitable dumping ground”.

The proposed central dump scheme was debated amongst Corporation Council members and sites at Tivoli and Dunkettle were visited. Nothing came out of the proposals immediately though, but the idea was indirectly green lit that the city should have a controlled dumping ground for all refuse, manure and mud collected. In 1934, one was established adjacent the Carrigrohane Road, which remained open until 1975, until the former landfill at Kinsale Road replaced it.

Caption:

1185a. Slum conditions in Kelly Street, Cork, formerly off Shandon Street c.1900 (source: Cork Public Museum).

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 12 January 2023

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 12 January 2023

Recasting Cork: Visions for Trade and Commerce

In the first week of January 1923, a monthly meeting of the executive of Cork Chamber of Commerce convened. Chaired by Chamber President John Callaghan Foley, John Gamon, American Consul in Cobh, and Mr A Canavan, representative of the United States Lines, Cobh, were also in attendance. The President, in welcoming the representatives of the United States, noted that Ireland owed much to the States for the relief afforded the country not only since the Act of Union, 1800, but especially during the Irish War of Independence. He wished for a formal invitation be issued on behalf of the Irish chambers of commerce to the United States welcoming a delegation of American industrialists and commercial men to Ireland.

Mr Canavan, on taking the floor, stated that very little was known of the industrial possibilities of Ireland in foreign countries and stated that if Ireland had an efficient publicity scheme in place, its natural resources would become more commercially important. He asserted: “At present foreigners merely thought of lreland as a sort of Emerald Isle where kings were always at cross-purposes… this country was on the eve of a big industrial revival, to meet the necessities of which, it was necessary to bring foreign representatives of commerce in close touch with industrial possibilities in this country”.

Mr Canavan detailed that the second International Meeting of the Chambers of Commerce was being held in Rome and 300 representatives of the States were expected to attend the meeting and had an itinerary marked out across other European countries but it did not include Ireland. He was of the opinion that if proper communication steps were taken, a number of the United States delegates could modify their arrangements as to include Ireland in the tour.

Mr Gamon read a few extracts from an official document setting out the business arrangements of the International Conference. He described that it was a function that had a distinctly international bearing on the world’s trade and commerce; “Ireland would be the loser by not taking part in the Conference as big problems dealing with international trade would be fully discussed”.

John Callaghan Foley, President, detailed that up to a few years ago Ireland’s trade and commerce began and ended with England – but in their more contemporary years the question of getting into contact with foreign countries was taken up by the Chamber. As a result, direct cargo and passenger services were brought into contact with the port of Cork from foreign ports like New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Brest, Le Havre and Hamburg.

The Chamber was in constant touch with the Irish Consul’s residence at New York, Paris, Brussels and Genoa and was successful in securing much direct business for Irish firms. Since the Moore-McCormack Line had begun to operate, 50,000 tons of merchandise had been carried direct from American ports to Cork, and a freight saving of up to £30,000 had been affected by the direct shipping. Brokerage through England, Liverpool harbour dues, demurrage, etc., had in the past added much to the cost of marketing foreign produce in Ireland.

John Callaghan Foley detailed that the Chamber, in spite of almost insuperable difficulties, had backed this direct service with American ports; “It appeared at present that the whole industrial and commercial fabric of this little island had broken down. It was not so, however, as even up to the close of last year Ireland imported £200,000,000 of foreign goods annually. In view of this figure, I am of the opinion that it would be advisable for this Chamber to get into touch with all other Irish chambers for the purpose of cooperating in inviting United States trade delegations to this country”.

Chamber member Mr Patrick Crowley maintained that the time was opportune, and that combined steps should be taken to issue a formal invitation to an American trade delegation. Referring to the state of the country he was of opinion that Ireland looked much worse through Irish eyes than through foreign ones; “Considering the fact that there was trouble everywhere in all countries political, economic social and moral, Ireland is only experiencing its share of an economic and political unrest which had permeated the peoples of all countries”. He regarded it as a big surprise that Ireland was left out of the itinerary drawn up for the American meeting delegates to Europe. He personally knew as a director of the Irish International Trading Corporation (Cork), Ltd, that US firms were very keen on keeping up business with Irish enterprises.

John Callaghan Foley concluded that in view of the fact that Messrs Henry Ford and Son had come to Cork and were at present employing 2,000 men at their Cork works, that other American firms ought to be quick in realising the facilities offered along the 14 miles stretch from Cork to Cobh. Suitable sites for large factories were available. Mr Canavan agreed with the ideas that the development of Cork Harbour offered great advantages. He stated it was his opinion that Cork, so far as natural advantages were concerned, ranked first among Atlantic ports. He had hoped that liners of 200-foot length would soon visit Cork and place the harbour as part of their routes.

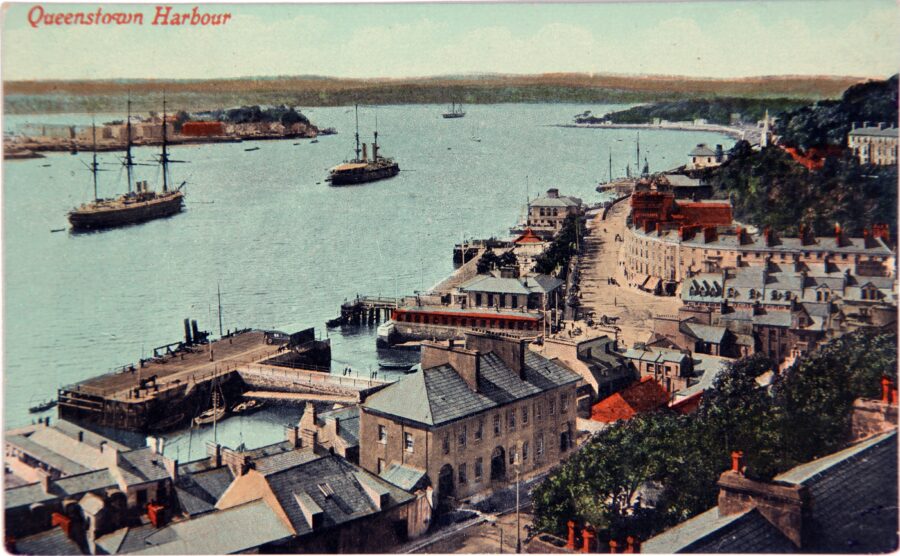

Caption:

1184a. Queenstown, now Cobh, c.1920 (picture: Cork Public Museum).

Happy Christmas!

The Blessing of a Candle

by Cllr Kieran McCarthy

Sturdy on a table top and lit by youngest fair,

a candle is blessed with hope and love, and much festive cheer,

Set in a wooden centre piece galore,

it speaks in Christian mercy and a distant past of emotional lore,

With each commencing second, memories come and go,

like flickering lights on the nearest Christmas tree all lit in traditional glow,

With each passing minute, the flame bounces side to side in drafty household breeze,

its light conjuring feelings of peace and warmth amidst familiar blissful degrees,

With each lapsing hour, the residue of wax visibly melts away,

whilst the light blue centered heart is laced with a spiritual healing at play,

With each ending day, how lucky are those who love and laugh around its glow-filledness,

whilst outside, the cold beats against the nearest window in the bleak winter barreness,

Fear and nightmare drift away in the emulating light,

both threaten this season in almighty wintry flight,

Sturdy on a table top and lit by youngest fair,

a candle is blessed with hope and love, and much festive cheer.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 22 December 2022

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 22 December 2022

Journeys to an Irish Free State: Recasting the Southern Capital

Hidden amongst the multitude of news pieces in December 1922 in the Cork Examiner is an insightful, ambitious and detailed write-up on a lecture on town planning by Cork Corporation’s Joseph Delaney to Cork Chamber of Commerce. The main aim of the talk was the thinking through of the “future improvement and the better shaping of the city”.

It was perhaps serendipitous that the talk was almost published on the second anniversary of the Burning of Cork and also within days of the Irish Free State being formed – but all of the thoughts within the talk were to define the city’s development across the decades of the 1920s and 1930s and still echo somewhat in the current day.

Originally published in the Cork Examiner on 18 December 1922 (p.8), the article was written up in pamphlet form and can be viewed in the National Library, Dublin. In the report Joseph stresses that the urgent duty of Cork was to create a plan of city improvement and extension, develop it in gradual stages and put available financial resources to pursue such ideals, that coupled with a re-generating policy to modernise it.

According to Joseph, Cork was badly in need of the following public conveniences, utilities, and improvements. He lists a 26 point priority list of which housing and slum clearance are at the top of. He advocated for 2,500 houses on well-chosen sites, with roads, sewers, water supply, and light. What he described as the city’s “house congested jungles” should be cleared, narrow streets should be widened and house density should be reduced where there was excessive congestion.

Joseph called for the acquisition of derelict sites, which he called “form a chequer-board” on the map of the city. His vision was to lay them out as open spaces and recreation grounds – that coupled with at least two formal parks – one for the northern and one for the southern district of the city. He also envisaged a city stadium for “general sports, athletics, hors and agricultural shows, public competitions, galas, band promenades etc”. He called for new main drainage and sewage disposal schemes on “modern principles” of sanitary engineering be constructed.

An urban mobility plan was in Joseph’s top ten of priorities. He urged for a new and improved tram service and a pavement for 65 miles of roads and streets in a “most modern road surface treatment”, a new and improved tram service, complete with latest methods of public lighting. Public conveniences such as toilets, a new well equipped abattoir, and a new suitable cattle market, a new central fire station, a new city hall, and new market spaces for meat, provisions, vegetables and fish.

Joseph Delaney’s back story reveals a learned man. Arriving to Cork Corporation in 1903, Joseph amassed nineteen years’ experience within the organisation. Joseph was also interested in Irish industrial and language movements, in the country’s national well-being, its educational advancement and in economic reform.

W T Pike in his Contemporary biographies’, published in Cork and County Cork in the Twentieth Century by Richard J Hodges in 1911 reveals that Joseph (1872-1942) was educated at St Vincent’s College, Castleknock, Dublin. Joseph trained as engineer and architect by indentured pupilage under well-known Dublin architect Walter Glynn Doolin. Joseph became a certified surveyor under the London Metropolitan Building Act, combined with private study in the engineering courses of the Institution of Civil Engineers, and of the Institute of Municipal and County Engineers.

Joseph served on the temporary Civil Staff of the Royal Engineers and was Assistant City Architect in Dublin, for five years. In 1903, he was then appointed City Engineer of Cork. On taking up the Cork post he immediately set about improving the water supply system and reducing the abnormally high rate of water wastage in the city.

However, one of the many legacies Joseph left Cork City came from a visit to the US on an inquiry into American methods of municipal engineering and architectural practice, and an inspection of public works of civic utility. There he learned about the remodelling of American towns and cities to meet the modern requirements of their everyday life and that this was a common feature of civic pride in America.

In a spring 1921 report penned by Joseph (available in the City Library), Joseph outlines in a few pages the need for Cork to have a town plan noting that “town planning should be considered advantageous in Cork, with a view to the future improvement and better shaping of the city”. He called for this work to be investigated by specially appointed commissioners, consisting of prominent citizens and commercial and professional life, together with representatives of municipal councils.

Planning ahead was crucial and Joseph argued; “The schemes produced, and in many cases accomplished, have resulted in the complete re-casting of the plans of cities, with consequent improved public convenience, and enhanced amenity of environment”.

At a conference of the principal citizens led by Joseph, and held at the Cork School of Art, in March 1922, the Cork Town Planning Association was formed, and subsequently well-known architects Professor Patrick Abercrombie, and Sydney Kelly were invited and agreed to act as special advisors to the Association. The Association’s representative Executive Committee, which was comprised of a small committee of technical experts, were asked to prepare the data and suggest features for a town planning scheme.

Unfortunately, Joseph resigned in 1924 from Cork Corporation because of illness brought about by pressure of the reconstruction work on St Patrick’s Street. Joseph is said to have retired from Cork to Clonmel. From circa 1926 until 1936 he kept an office at 97, St Stephen’s Green, Dublin. He died at Clonmel in 1942.

Celebrating Cork (2022, Amberley Publishing) by Kieran McCarthy is now available is now available in any good bookshop.

Happy Christmas to all readers of this column.

Missed one of the 50 other columns this year, check out the indices at Kieran’s heritage website, www.corkheritage.ie

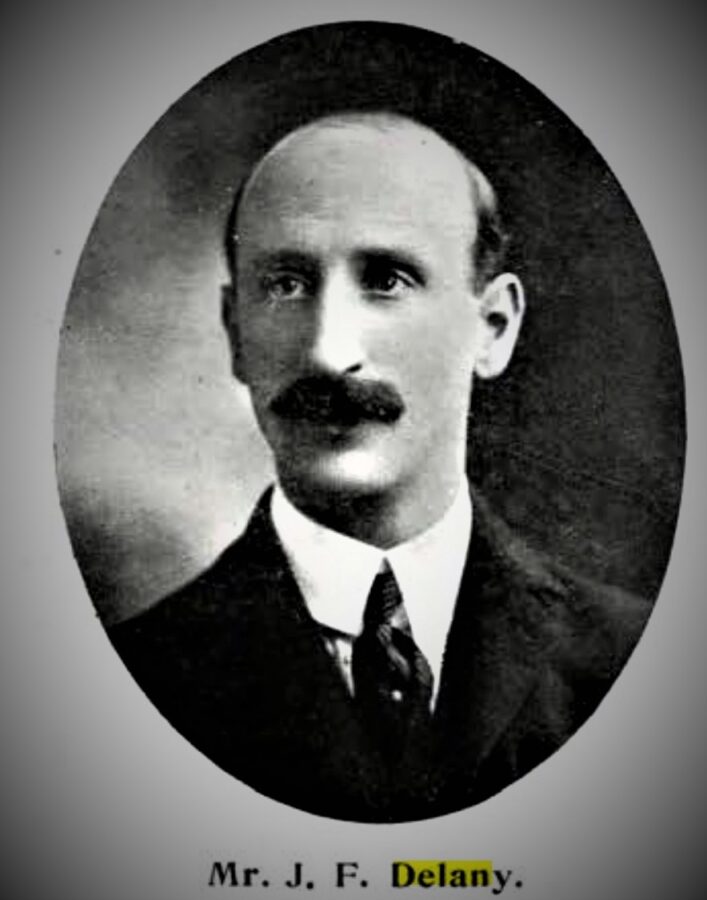

Caption:

1118a. Joseph F Delany, City Engineer, c.1911 in W.T. Pike’s “Contemporary Biographies”, published in Cork and County Cork in the Twentieth Century (1911) by Richard J. Hodges.

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 29 September 2022

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 29 September 2022

Journeys to a Free State: A City of Rifle Fire

Despite the securing of Cork City by the National Army of the Irish Provisional Government across August 1922, Anti Treaty IRA members continued to pursue their aims, and Civil War was brought to street corners and into buildings. The Cork Examiner outlines several tit-for-tat activities across September 1922.

In the early hours of 2 September 1922, the forces of the National Army stationed in the city in the course of raiding operations, discovered what was a munitions factory in the house at the corner of the South Mall and Queen Street (now Fr Mathew Street). The munitions were discovered in the upstairs portion of the house over 17a South Mall or 1 Queen Street. A gentleman named Mr McGuckin, who resided there has been arrested, and was detained.

The discoveries made by the troops during their search of the premises included: three boxes of bombs, two bags of bombs, about eight rifles, the same number of revolvers (of either Colt or Webley pattern), large quantities of ammunition, mostly of the dum-dum and explosive type, and machinery for the manufacture of bombs and ammunition.

The two bags of bombs were found underneath the flooring in one of the rooms. The machinery, which was of a very elaborate nature, was right at the top of the house. It was in perfect working order and was capable of turning out quantities of bombs and ammunition, while special provision had also been made for the manufacture of dumdum bullets. The ammunition found on the premises was principally of this type, and included bullets for Thompson and Lewis guns, as well as rifles, revolvers, and even pistols.

On 2 September in the morning at 10.15am an attack was made on the soldiers stationed at one of the city’s national army bases at the Cork City Club, Grand Parade at the intersection of the South Mall. Machine gun and rifle fire was opened upon them. One was killed and fourteen injured. The attack was opened on them from the opposite side of the river – Sullivan’s Quay.

A motor bicycle and sidecar were proceeding slowly up the quay from Parliament Bridge in a westerly direction. A machine-gun was mounted in the sidecar attachment and trained on the Grand Parade. As soon as the soldiers came into view of the two men in this vehicle the machine-gun opened fire.

At the same moment two men with rifles were seen to fire on the unarmed soldiers from the roof of a house a little to the Parliament Bridge side of Friary Lane, which turns off Sullivan’s Quay at right angles, almost opposite the National Monument. Two other men opened fire from another low roof on the western side of the corner of Friary Lane. The wounded were all brought to the Mercy Hospital.

In the early hours of 5 September snipers were active and several of the National Army posts in the city were attacked. None of the soldiers was hit. The only casualty was Miss Elizabeth O’Meara, who was wounded while in bed at her residence on the Grand Parade. Firing started in the vicinity of Victoria Barracks about midnight, but seemed at first to be merely an effort to draw the fire of the National soldiers. As the morning advanced, however, the firing developed, and machine-gun fire could be distinctly heard for a long time about daybreak.

About 2am an attack was made on the Metropole Hotel, and the sniping in the vicinity of this building continued for nearly six hours until about 7am. Near dawn, shots were fired at the City Club base, Grand Parade, from all sides, but particularly from the rear and from the south side of the river. Replies of gunfire from the National soldiers had the effect of quickly silencing the snipers. Casualties amongst the IRA, if any, were unknown. All the National Army soldiers escaped unhurt.

The Cork Examiner records that on the morning of 7 September, a series of raids on mails were made in different districts in the city, about 25 postmen (of 47 active postmen that morning), engaged in delivering letters, were held-up and the contents of their bags being appropriated by armed men. In each case the postman was confronted by two or three men, who produced revolvers and forced him to hand over the contents of his post-bag. In many cases the postmen had commenced delivery before being hold-up, but in a few cases all the letters were taken. Some of these were recovered by the Post Office. They were handed by an armed civilian.

About 10pm on 13 September night some eight to ten soldiers – all unarmed – were testing a motor lorry, which had been undergoing repairs at Messrs Johnson and Perrott’s garage in Emmet Place. They took the car for a short trial spin towards St Patrick’s Bridge, and it was while doing so that the bomb was thrown at the lorry. It fell into the car, but, very fortunately, did not explode. The person who threw it escaped into the darkness.

About 9.15pm on 18 September 1922 machine gun fire was opened at the National Army troops posted at Moore’s Hotel on Morrison’s Island. The attack came from the opposite side of the river, where a motor car was believed to have had a machine gun. There were no casualties among the troops, but a Mrs Haines, who was a guest in a house adjoining Moore’s Hotel, received several bullet wounds. She was brought to the Mercy Hospital in a critical condition.

Shortly after 9pm on 28 September a small party of National Army troops were travelling along the Ballvhooly road towards the city. A bomb was thrown at them from inside a gateway, which led to the backs of some houses, and from which an easy escape could be made. Due probably to the aim of the thrower the bomb went well wide of its mark, and none of the troops sustained any injuries. Indeed, beyond a small hole in the road and a few broken panes of glass in the houses in the immediate neighbourhood, no physical damage was done, but the local neighbourhood was highly concerned.

Many thanks to everyone who attended the 2022 season of public historical walking tours.

Caption:

1170a. National Army soldiers in front of the commandeered Cork City and County Club at the intersection of the Grand Parade and the South Mall, photographed by W D Hogan (source: National Library, Dublin).

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 22 September 2022

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 22 September 2022

Launch of A History of the Glen

Gerard Martin O’Brien’s book on The Glen in the heartland of Cork’s northside is an impressive landmark and beautiful publication. It is a personal memoir brought alive with deep research on the story of such a space of industrial heritage but also the movement in recent years to restore the space as one of Cork’s leading biodiverse parks. The book is entitled Faeries, Felons and Fine Gentlemen, A History of the Glen, Cork, 1700-1980 and is being launched at 7.30pm at Mayfield Library on 23 September, aka on Culture Night.

The book is intermixed with Gerard’s stories of growing up in the heart of the Glen to the stories of the various industries, which harnessed the power and space of the Glen river valley. In his introduction, Gerard noted about playing in the Glen amidst the ruins; “My Glen, the one I grew up in, had such diamond-like qualities as far as I was concerned. Yet, as a youngster, when I explored the old ruins, mused on the function of old waterways, and listened to stories of past activities and occupations, I should have understood how my ‘permanent world’ was already changing and had always been changing”.

Gerard’s idea for the book had its origins in the chance discovery of an old photograph of Goulding’s factory, which is not just remarkable for the clarity of the image, but also surprised Gerard with the clarity of recall the image engendered. It was one of three taken by the intrepid aerial photographer, Captain Alexander (‘Monkey’) Morgan in 1956, which Gerard discovered in the Morgan Collection in the National Photographic Archive.

Gerard describes that the Glen River is neither big nor long but rises from the springs and marshes in Lower Mayfield and Banduff and flows west. It is joined at Valebrook by another stream emanating in upper Ballyvolane (Ballincolly). The enlarged river flows through the Glen. At Blackpool it joins the bigger and longer Bride River. The river provided power to many industrial enterprises over the past three hundred years. Five mill ponds of varying sizes once punctuated its course at relatively even intervals between where it first emerges near the Fox and Hounds Crossroads, and Spring Lane at the western end.

As far as a history of the Glen is concerned, Gerard details that there were many versions of what the Glen had been like ‘before’ and the farther he went back in time, the less clear-cut anything became. Even the names changed and changed again through the lack of standard spelling or mistranslation: Glounapooka, Glounaspike and Glounaspooks are now forgotten names once associated with opposite ends of the Glen.

Before the eighteenth century, Gerard speculates the activities that went on there. For instance, the trees that covered the Glen in the nineteenth century were English elm, which had been introduced to Ireland in the seventeenth century. For such trees to colonise an area, there must have been a clearance of native woodland – but by whom and why is not recorded. Of arable faming Gerard denotes: “There is evidence to show that the eastern part of the Glen, being arable, was farmed long before the eighteenth century. Then of course, going back into prehistory, the post ice-age landscape would have been entirely different, and at some stage it is possible that much of the lower Glen, possibly all the western half, was a big lake before the river eroded its way through the rocky pass”.

Gerard’s research details that the quarrying of stone, sand and gravel probably represented the first efforts at exploitation of the Glen’s resources. Historic documents refer to a ‘north’ and ‘south’ sand quarry in the eighteenth-century Glen. A third quarry was also opened in the nineteenth century on the borders of Cahergal and Clashnaganiff townlands. The rock on the south face of the Glen was also quarried, most likely to build the mills in the eighteenth century and the distillery in the early nineteenth. However, from examining a succession of early OS maps, Gerard argues that it is probable that the quarrying of stone continued, at least periodically, throughout the nineteenth century. The sand quarries have now either been built over or landscaped, but evidence of the stone quarries can still be traced.

The earliest date for which references can be traced for any of these mills is the beginning of the eighteenth century. Gerard argues that it is not impossible that one or two ‘prototype mills’ existed before that. The Dodge family, one of the first families to make their mark on the Glen, may have prospered but their prosperity was a relative one: they were comfortable but did not amass a large fortune and plied the same trade for a century.

Gerard maps out and writes in detail that towards the end of the eighteenth century, flax milling was established at the eastern end of the Glen, but the process appears to have lasted only thirty years at most, before the mill was converted to a starch mill. The only other manufacturing process to be carried on in the Glen at that stage was iron working – a trade as old as corn milling – so it appears that a slow, steady, hardly changing way of life prevailed for the first century covered in this work. Gerard describes that in effect, the mills are centred in two clusters; “The iron mill, flax mill and one corn mill were located at the eastern end of the Glen where the landscape is broader, and the hills rise gently from a wide, marshy base. The malt/corn mills and the distillery/fertiliser factory were at the western end where the hills rise steeply to approximately one hundred feet and the valley floor has a characteristic V-shape”.

With the beginning of the nineteenth century the establishment of the distillery introduced an industrial model to the Glen. Gerard outlines that the first of these individuals, Humphreys Manders, went bankrupt almost immediately. The Perrier Brothers, with more money and experience, straightaway took his place. They did not live in the Glen and had other interests elsewhere in the city. The nineteenth century would see several such individuals associated with the Glen. Then, as the twentieth century dawned, a new type of industry dominated the landscape – Goulding’s Fertilisers, which was arguably the first Irish multinational industry.

Faeries, Felons and Fine Gentlemen, A History of the Glen, Cork, 1700-1980 by Gerard Martin O’Brien – copies can be bought at the launch or contact Gerard through his website www.bluehorsepress.net.

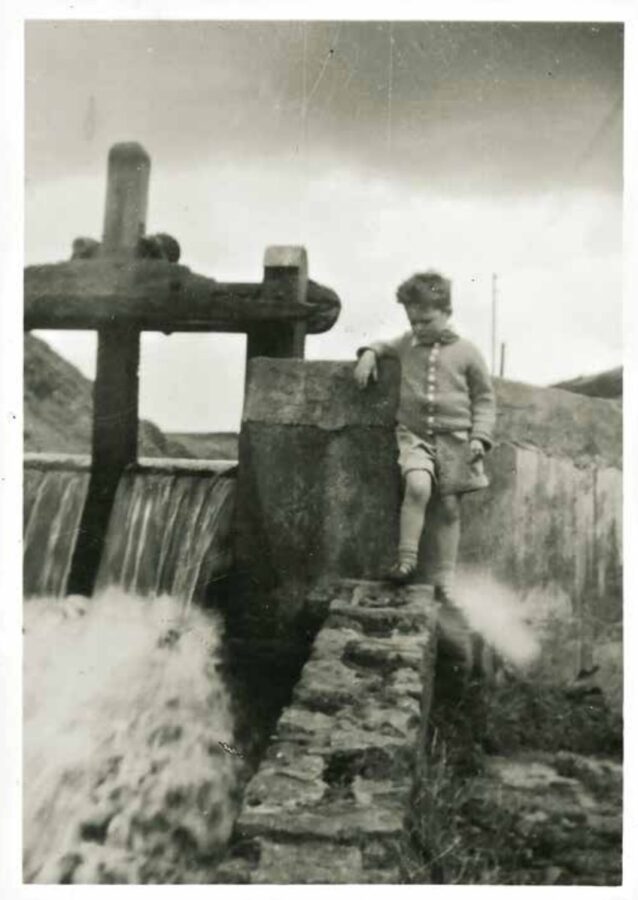

Caption:

1169a. Gerard Martin O’Brien, age four, standing by the ‘Hatch’, The Glen, circa 1957, from Faeries, Felons and Fine Gentlemen, A History of the Glen, Cork, 1700-1980 by Gerard Martin O’Brien.

Daly’s Bridge with Tom Scott & Kieran, April 2022

View: “The bridge that must legally wobble”, Daly’s Bridge, AKA The Shakey Bridge, with Tom Scott and an interview with Kieran McCarthy

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town, 14 April 2022

Kieran’s Our City, Our Town Article,

Cork Independent, 14 April 2022

Journeys to a Free State: A Civil War Looms

By mid-April 1922, tensions between the pro and anti-Treaty sides intensified further. Words such as “civil war” began to creep into speeches of the anti-Treaty side. The first acts of disobedience of Irish Free State law also occurred. This was the beginning of the Irish Civil War. On 14 April 1922, about 200 anti-Treaty IRA militants, with Rory O’Connor as their spokesman, occupied the Four Courts in Dublin.

From 1919 to 1921, Dublin based Rory O’Connor was Director of Engineering of the IRA. On 26 March 1922, Rory was one of the anti-Treaty officers of the IRA that hosted a convention in Dublin, in which they rejected the Treaty and renounced the power of Dáil Éireann. However, they were willing to discuss an approach forward.

The convention met again on 9 April. This time they set up a new army constitution and put the army under a newly elected executive of sixteen, that would select an army council and headquarters staff. Rory was one of the sixteen and within five days of the new constitution, the Four Courts were seized. They also took other smaller buildings in Dublin deemed as being connected with the former British administration, such as the Ballast Office and the Freemason’s Hall. The main aim was to incite British troops, who had not departed the county yet, into confronting them. There was a hope that the war with Britain would restart and galvanise the pro and anti-treaty sides together with a common purpose.

As described by the Cork Examiner, small crowds of curious onlookers initially gathered over the weekend of 15 and 16 April in the neighbourhood and beguiled their time inspecting the sandbag defences and timber barricades in the windows and at the entrances of the Four Courts. In several of the windows overlooking the quays loopholes had been made by smashing the glass, and the apertures were partly filled by stacks of books. A stand-off began, which was not resolved until the shelling of the building by Irish Free State Troops began on 28 June. Two days later a large explosion destroyed the building, leading to the surrender of the garrison.

On Sunday 16 April, in a speech delivered by Cork TD Mary MacSwiney at the Mountain Chapel (Ballinhassig) she declared that the people of Ireland could not go into the British Empire and to do so would be a disgrace to every man who ever died for Ireland. The audience was composed of the congregation that attended the 10.30am Mass. Leaflets were distributed at the church gate, recalling the events of 1916, and declaring that “the Republic lived on and was in 1918 constitutionally established by the free vote of the Irish people, and was maintained by the IRA in spite of all the forces England could put in the field”. The pamphlet continued: “Easter Week is with us again. We now celebrate the sixth anniversary of the proclamation of the Republic, but to-day you are asked to disestablish the Republic; to take, an oath of allegiance to England’s King and to come into the British Empire”. Finally, the pamphlet asked: “Will you do it?” and concluded with the admonition: “Remember 1916”.

Miss MacSwiney, who had a cordial reception, said that in December 1921, two weeks before, the Treaty was signed, she spoke in the village of Ballinhassig. She noted then what she believed that not one single Irishman would accept compromise, and that Ireland’s honour was safe in the hands of the delegates who went to London. She then believed in them. She felt that they went to London to try to find a way to peace with honour, but not to give away the Republic of Ireland that the men of Easter Week died to establish. She deemed that those men gave away the Republic and that they had told the people that they got the last ounce that England would give, and that the alternative was “immediate and terrible war”. Mary advocated that Britain was fighting a war in Egypt and in India, and that they had no money to follow through on the war element.

Referencing Irish patriots of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Mary commented on what they stood for; “If we allow Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith and the rest of the men who were trying to turn down the Republic to establish a government in this country they would have to imprison, and perhaps to torture and to kill the men and women who stood where Tone and Mitchell and Davis and the men of 1916 stood, for these would not go into the British Empire with their heads or their hands up. They were going to remain citizens of the Irish Republic, and they would not allow that to be turned down except over their dead bodies”.

Mary wished to advise Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith to say to British Prime Minister Lloyd George: “We will not have civil war in our country. We believe that your Treaty is good, and we might have worked it, but it is not worth civil war, and we won’t risk that. That was what honourable men would say, for there could be no peace which included a Governor-General in this country and an oath of allegiance to an English king.

Mary appealed to the people to stand true to the Republic for which so many great men had died. They had only to stand true for a little while longer, and they would win. Concluding she noted: “As sure as England tried to impose on them a Governor-General or an oath of allegiance the Irish would stand against it. Where England had interests they would destroy them. They would fight her in England, fight her in Ireland, and fight her all the world over until she came to terms with the Irish Republic”.

Caption:

1146a. Mary MacSwiney TD, 1921 (Source: Houses of the Oireachtas Archive).

Kieran’s Press, Pub Dereliction & Housing, 26 February 2022

26 February 2022, “Independent councillor Kieran McCarthy said that, while any measure to tackle vacancies in Cork is welcome, the new regulations could open up a ‘can of worms’. “Many of these pubs are historic structures within villages and towns. My concern would be that someone could now just come along and create some modern monstrosity and not need planning permission”, Pubs to homes plan: Residential potential for disused pubs in Cork, Pubs to homes plan: Residential potential for disused pubs in Cork (echolive.ie)